Built Heritage In Small Towns A Unique Tourism Opportunity: Case Of Shiv Kund, Sohna

The small and medium towns of our country are abundantly rich in built heritage with varied value and significance for a wide range of stakeholders. While the established tourist destinations attract visitation, the heritage that thrives in most of our small towns represents a lost opportunity. Popular tourist destinations in the country deal with visitor numbers beyond their carrying capacities, resulting in adverse effects for the local communities. A focus on the smaller towns would allow both domestic as well as well as international visitors to experience the unique value that they present, leveraging the interest of those who are on the lookout for more dynamic and diverse experiences. Shiv Kund in Sohna is an example of a site that has all the credentials to attract a wider range and numbers of tourists or visitors. The case establishes that the rich built heritage, strong stakeholder connect and value of such sites in our country represents a lost opportunity for a nation that is trying to build itself as a tourist destination. The take a ways for professionals, students and those in government can be significant.

INTRODUCTION

It is no secret that India is largely a heritage tourism destination. There has been a lot of conversation how with investments in its infrastructure and services (tourism related), the number of international tourists visiting in India can be grown to a more acceptable and representative number. It is true that our 1.2% share of the international traveller pie is rather dismal when compared to the likes of France, UK, Germany and many other nations. Governments have consistently identified tourism as a driver of economic growth and promised steps to support the tourism related ecosystem at large with an eye on the high spending international traveller. The fact that inbound traveller statistics (international travellers) have little to show is question for the government and policy makers to consider, if not answer.

The other interesting and again rather well known trend with respect to tourism in India is the fact that it is largely driven by a massive domestic market, with nearly 400 million Indians traveling across the country for leisure, religious pilgrimage, adventure travel etc, the domestic traveller is thus in prominence. A growing middle class, with disposable income and willingness to travel for a range of reasons has emerged as the key driver our tourism related economic activity in the country.

This paper looks beyond the above generally accepted facts and aims to identify the significance and opportunity that built heritage in our small or medium sized towns presents. These are locations that are not a part of any well-defined or marketed tourism circuit, but their heritage significance renders these non-descript towns with amazing built heritage that has tremendous cultural, religious and social importance to become potential high impact tourist destinations. The Shiv Kund in Sohna a small town in Haryana is one such example, it is a representative of sites in many such towns in India that today represent an opportunity lost for not just the communities around them but also for domestic and international visitors who lose out on visiting and experiencing these locations.

About the Shiv Kund

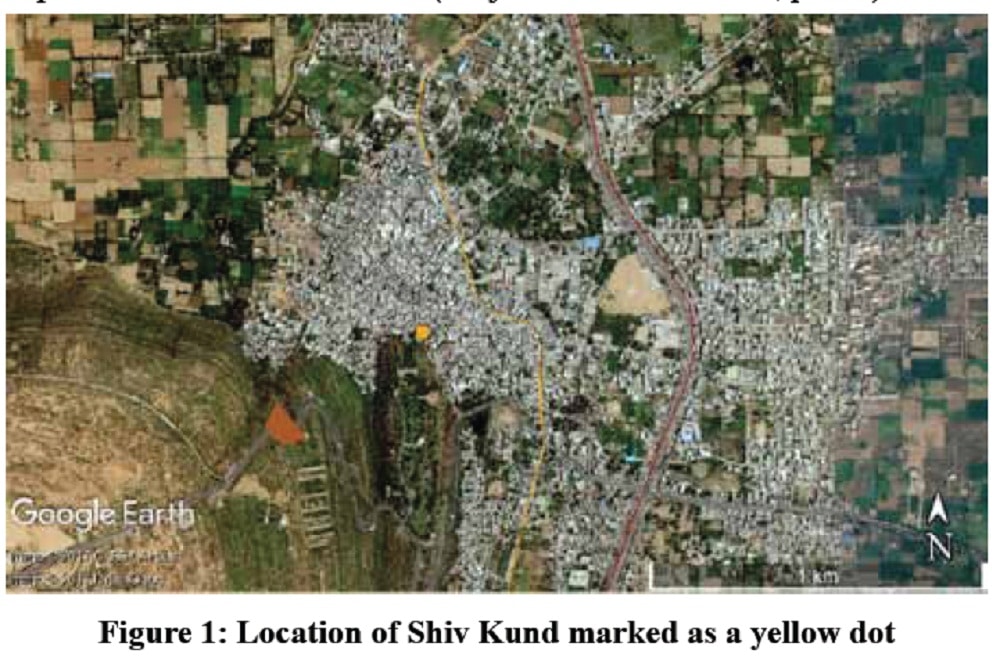

The Shiv Kund at Sohna in Gurgaon District is a natural hot spring at the foot of the Aravallis, established as a Hindu teerth (place of pilgrimage) with its water serving as a cure for skin diseases and rheumatism. The site is located in the heart of the dense core settlement, with the Aravallis as an immediate backdrop towards the south. The growth of the town is limited to the south of the Kund, due to the steep rise of the hill. This part of the town is said to be established by Sisodia Raja Sawan Singh from Jalandhar, who expelled the Khanzadas in 1620 (Punjab Government 1910, p. 246).

Maharaja Agrasen Road (highlighted in yellow) runs through the core town. Shiv Kund is accessible on foot from this motorable road, or another road towards the south, on top of the hill. The Bus stand was earlier situated on Maharaja Agrasen Road, providing easy access to the Kund, but now moved to the Sohna Road (highlighted in red). The site preceded the town established by the Raja, as it finds mention in the Ain-i-Akbari from the 16th century as being near the town of Sohna on the summit of a hill (Jarrett 1891, p. 281). As per the District Gazetteers from the 19th and early 20th century, the town existed to the north and west of the present settlement in the 15th to 16th century as evidenced by architectural remains from the Kamboh and Khanzada period (Punjab Government 1910, p. 246).

Till a few decades ago, the Maharaja Agrasen Road used to serve as the main spine of the town, with the main market and the Bus Stand being situated there. The development pattern of the town suggests that this was the main route, with the core town between this and the Aravallis that form a natural barrier to development. The Shahi Masjid, Dargah of Najm-ul-Hak1 and the Shiv Kund, all are located at a distance of about 100 metres from the road. The visitors would get off at the Bus Stand and access the site on foot. At present, the Bus Stand has moved out to the Sohna Gurgaon Road, changing the access pattern for those using public transport. Private vehicles are parked near the Fuwara Chowk, either at the Old Tehsil, now converted to Post Office or the Mandi. The access roads from here to the Kund are lined with commercial activity on the ground floor. Another access to the site is via an offshoot from the Taoru2 Road that climbs up the Aravalli to the south of the Kund, built by Late Chaudhary Devi Lal who served as the Chief Minister of Haryana twice, in the 1970s and 80s. The Tau Devi Lal Road stops short of the Kund at a high contour. The Kund is accessible from this point through a steep climb down the hill on foot. A tourist resort named Barbet was established on top of the hill to the south of the Kund in the 1970s, accessible from the road from Sohna towards Taoru. Barbet was established to leverage the popularity of the Shiv Kund and promote the destination. Water from the Kund was earlier pumped up to the resort for the benefit of the resort visitors, becoming a cause of drop in the water level at the Kund.

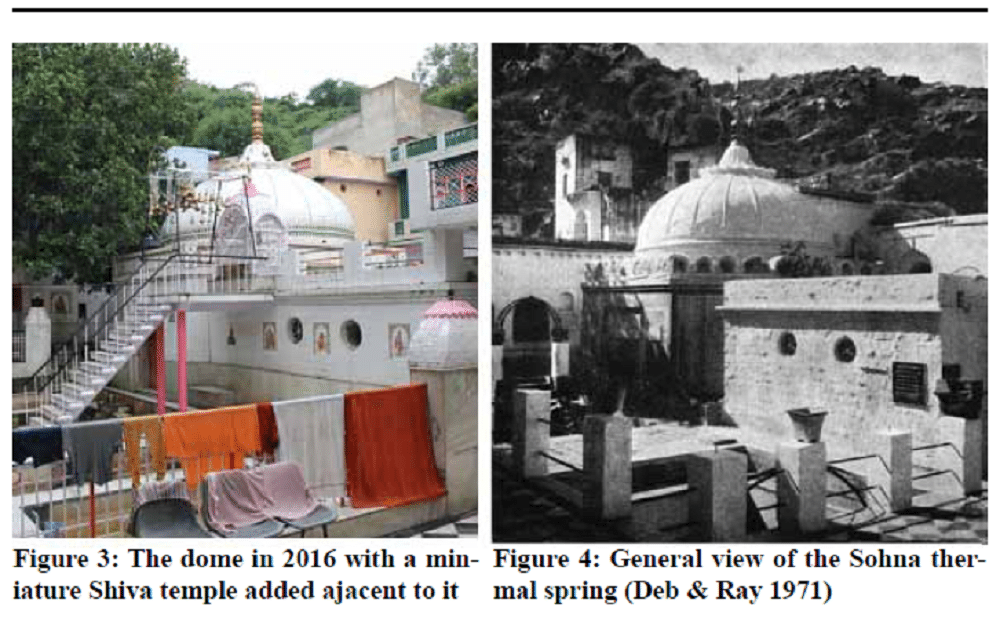

The earliest documented reference of the hot sulphur spring at Sohna3 is in the Ain-I-Akbari by Abul Fazl Allami from late 16th century (Jarrett 1891, p. 281): ‘Near the town of Sahnah is a hot spring on the summit of a hill, the peculiarity of which is undoubtedly due to a sulphur mine.’ In the same reference, Suhnah is listed as having ‘a stone fort on a hill; here a hot spring and Hindu shrine’ (Jarrett 1891, p. 293). The site is referred to as a historic site with stories around its discovery, starting with one recorded in the 19th century4. It is acknowledged as a built heritage site and an Indo-Islamic monument as a part of documentation undertaken by organisations such as Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) Haryana (Jain & Dandona 2012, p. 158) and American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS n.d.) over the last decade. Over time, the site has seen physical transformation and multiple overlays of meaning. It is in use at present, managed by a local committee formulated post India’s Independence. There has been an intensive coverage of the site in Hindi newspapers such as Punjab Kesari, Amar Ujala, Dainik Jagran, Dainik Bhaskar, Dainik Tribune, Bharat Link, Gurgaon News and Hindustan Times over the last two decades. The main aspects of discussion include the religious and medicinal significance of the site and visitation and activities on festivals and other important days as per the Hindu calendar; concern over the water level of the Kund, including government apathy and contestations in measures taken to solve the issue. The presence of sulphur in the water is contested in some reports, while security concerns, visits of eminent personalities and election of the Kund Committee are other aspects covered in the coverage.

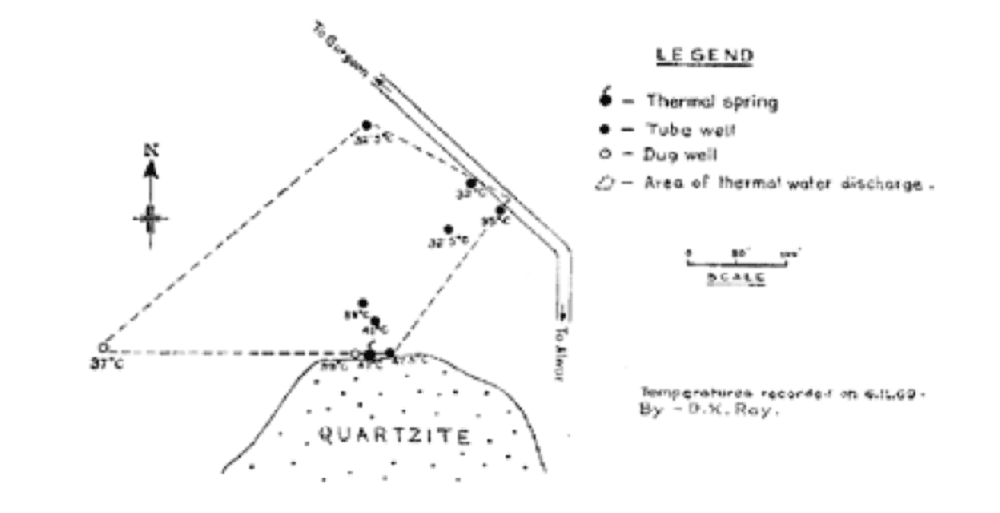

Map of the region around the thermal spring marking ‘tubewells and dug wells with water temperature higher than the atmospheric temperature’ (Deb & Ray 1971, p. 369)

In records from late 19th century, the town of Sohna was known to have long been celebrated for its hot sulphurous spring, possessing strong medical qualities. In the section on geology of the District Gurgaon in the Gazetteer from 1884, the sulphur spring at Sohna merited a two page description. Further, there has been interest in the thermal spring, from the geological perspective since 1882. Deb & Ray (1971, p. 364) refer to works by Oldham in 1882 who charted the temperature of the water and Ghosh in 1948 who conducted a spectroscopic examination of the water. In 1971, the spring was recorded as a commercial bathing centre by the authors, involving geological, hydrological and chemical studies to suggest possible origin.

The price of land in the core town area is one fifth of the price in the new colonies being established. This may be a deterrent for the local population to move out into the new colonies. At the same time, there is a possibility that the economically stronger categories of residents would move out to the newer areas, especially if they do not find value in living in the core town. The presence of the Kund, benefits drawn from the social, economic and political environment and the ties that they have with the place have kept some of the older families in the core town till now, while many have moved out to Delhi and other cities due to better livelihood possibilities and aspirations.

At present, the town is a Municipal Council5 with 21 wards, each governed by an elected representative. As per the 2011 Census of India, the town has a majority of Hindu population with 88.54% Hindus and 9.85% Muslims. Hindus populate the core town spread around the Shiv Kund. It is located in Ward 16 that includes Thakurwada, Pathanwada, Gujjar Ghati and Library Chowk area. Thakurwada houses Rajputs while Pathanwada originally had Muslims who migrated to Pakistan after the Partition of India and were replaced by Punjabis. The Library Chowk area is predominated by the merchant class or baniyas. The area surrounding the Kund is referred to as Mahajan Mohalla, and the commercial activity on streets towards the north of the Kund is supported by the bania or mahajan community. The residences to the south of the Kund are still occupied by descendants of the original residents. These courtyard houses with stone walls and traditional architectural vocabulary could be dating from 18th century and suffer due to subdivisions and lack of maintenance.

View from the terrace of west block of Shiv Kund complex (left) and view of the western wall with the street leading up to School run by Shiv Kund Committee (right).

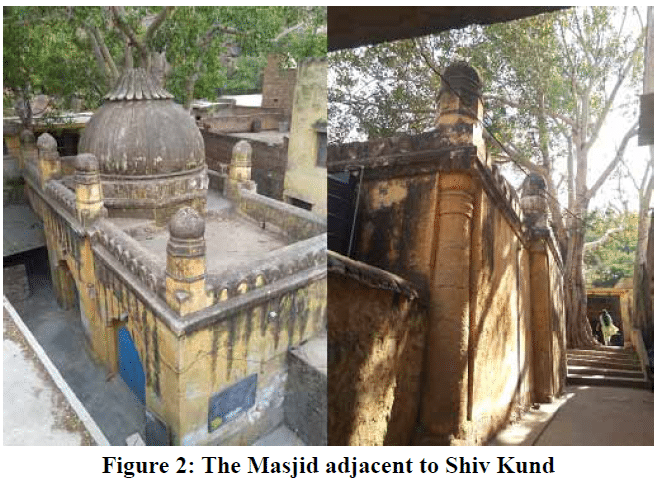

Right adjacent to the Kund, towards the west, there is a mosque said to be built by Aurangzeb (refer figure 2). The mosque is separated from the Kund by the western block of the Shiv Kund complex. The placement of the mosque with its eastern façade facing the Kund complex would have been consciously undertaken, to enable accessibility from the Kund side. The politically charged intervention is now fully marginalised, as the mosque is in use as a private school, with no physical access from the Kund and visual access only from the terrace of the western block of the Kund complex. The mosque is hidden away even in satellite imagery, tucked under the cover of a huge ficus tree growing adjacent to it. A street running to the west of the mosque leads to a charitable School run by the Shiv Kund Committee for the underprivileged. The built block of the School is right at the foot of the Aravalli hill.

The dharmshalas (rest houses) towards the east and west have pointedgroin vaulted ceilings and pointed arches facing the Kund. All of these structures have thick stone masonry walls plastered over. The one to the west is said to be built by a merchant from Jaipur6 in 1657 AD and the eastern one around the same time by a visitor wishful of a child, as per the Kund Mahant and plaques on site. As per the 1884 District Gazetteer, these were built by Princes of Gwalior and Bharatpur. The two verandas show minor variation in detail but complement each other architecturally. As is already apparent the Shiv Kund is a central landmark for the town and a driver of economic and social activities. This is further established in the stakeholder engagement with the site documented in the next section.

Figure 6: The dome of Sakhamjati Maharaj

The dome surrounded by built blocks on all four sides (refer figure 6), added over a period of time. The three tier block in the background defines the eastern edge, with the main gate in the north east corner. The upper floors of the eastern block are the Aryan Samaj temple.

Stakeholder Association

Destinations are essentially showcased by more than just the built fabric of sites that they encompass; it is the narrative that attracts the visitors. Tourists draw from the association of a range of stakeholders built over an extended period of time in the form of the socio-cultural context that the place represents. The Shiv Kund in Sohna has much to offer in that respect as represented by its association with a wide range of stakeholders.

The Shiv Kund was mentioned in the Ain-I-Akbari in 16th century and then in travelogues, gazetteers, research papers, government documents, nongovernmental organisations related to culture and heritage, and newspaper articles, 19th century onwards. Beyond this larger stakeholder group, it finds association among residents of the town and visitors, including eminent personalities.

The many stories of its origin reflect different types of association forged by the stakeholders. As per folklore documented in the 1884 Gazetteer, the origin of the spring is dated to around 1620 AD, when a faqir (Muslim Sufi ascetic) named Rakishu is said to have hollowed out a small basin to hold water that quenched the thirst of a 100,000 cattle of a Banjara trader (Punjab Government 1884, p. 181). This story of the discovery of the spring was narrated by representatives of the oldest Rajput family in Sohna. As a reward, the trader sold his merchandise7 and devoted the entire profit to the construction of an enormous tank, but with the initiation of the digging, hot water welled up and has flown uninterrupted ever since (ibid.). Interestingly, 1620 AD that is said to be the date of origin of the spring corresponds with point in history when the Sisodia (Raghubanshi) Rajputs of Jalandhar took over Sohna, after expelling the Khanzadas (Punjab Government 1910, p. 246). The story was narrated by the representatives of the Rajput family, and it wouldn’t be irrational to assume that the Sisodia Rajputs intertwined their own history in Sohna with this legend. The Sisodia Rajputs are said to have settled in Sohna as per the wish of their patron saint, yet they attributed the origin of the spring to a faqir. The miraculous episode celebrates the power invested in the faqir, and there is no association with any Hindu deity or saint, hence projecting a view uncorrupted by religious polarisation. The devotion of the profits by the trader towards the excavation of a tank in the story also sets a precedent of contributing towards the development of the miraculous site.

The plaques that narrate the ‘history’ of the site to lay claim to its historic importance give mixed up information where the dates do not add up meaningfully. The residents also have associations in the form of personal family histories, as against the collective narrative that is created for the consumption of the outsider.

Figure 7: Marble plaque affixed on a wall to the south of the domed structure on the main spring, constructing a history of the site

The story on the plaque that was fixed by the Kund Commiittee (refer figure 7) is a reconstructed version, to serve a particular agenda of positioning the site as a Hindu teerth sthal. In the study by AIIS (n.d.), the Kund has been grouped under Indo-Islamic monuments of Haryana. This is categorisation is opposed to the cultural or symbolic value that the present custodians want to maintain. The District Gazetteer from 1884 narrated a story involving a faqir (usually Muslim ascetic) while the current story relates it with Chaturbhuj Banjara whose Guru was Sakhamjati Maharaj, a sage from the Vedic Period, in whose name the Kund began being referred to as the Shri Shiv Kumbh Sakhamjati Maharaj. Raja Sohan, Sawan or Sawant Singh is considered as the founder of the town of Sohna, presumably from the Sisodia Rajput or Badgujar clan from Jalandhar that established the part of the town centred around the Shiv Kund as per the District Gazetteers (Punjab Government 1984; 1910). There are no references of the earlier layers of the town under the Kambohs or Khanzadas in the narrated history.

Another plaque on site outlines the brief history of the site. This was sent by the Deputy Commissioner of Gurgaon in 1990. This states that the town was established by Raja Sawant Singh, 850 year ago, which places it in the 12th century8. This is an unfounded claim, with no such mention found in any sources about the site. The setting up of a tourist spot in 1973 is said to have increased its fame nationally and internationally9. It mentions that the fort on top of the hill was built by Raja Raj Singh of Udaipur10. It also lists some famous personalities who originated from or resided in Sohna. It mentions that the site has ‘ancient’ temples11 and is a place of pilgrimage that was mentioned in the Ain-I-Akbari. This set of statements, each of which can be easily contested seems to have the agenda to promote tourism at the site by creating a sense of historic and religious significance.

The name of the complex at present, as mentioned on the main gate that has been renovated in 2013-14 is ‘Shri Shiv Kumbh Sakhamjati Aghmarshan Ji Maharaj’. The name depicts an association with the deity Shiva and the Guru Sakhamjati, who is said to be the Guru of Chaturbhuj Banjara who had discovered the spring, in one of the versions of the story. The Kund is a thriving centre of activity today with temples within that have generated an economic activity in the form of shops just outside the complex that sell offerings to be made at the temples. The access streets have lanes of food stalls preparing indigenous food and other such local commercial establishments that form a part of the local economy.

On the other hand, the stylistic and material appreciation of the structures could lead to categorisations such as Indo-Islamic, Pathan, Jat or Maratha considering the ubiquitous elements such as the arches, dome, vaults and brackets. These categorisations may find support in assertions by the Maulvi of Shahi Masjid, Sohna that the structure used to have Allah inscribed on it; narration in the Gazetteers that involve a faqir and record repair work by Rustam Khan Pathan in 1774. The mosque adjoining the Kund is still officially under the Wakf Board and the Lahore Court Case prior to Independence was fought due to the site being claimed by the Muslims, point towards a shared past. As per plaques on site, the Court case was ‘won’ by the Hindus, on the basis of a reference of the site as a ‘hot spring and Hindu shrine’ in the Ain-I-Akbari (Jarrett 1891, p. 293). The Kund Purohit set forth that during the Court Case, to maintain neutrality of the judgement, a Christian Judge was appointed. He further explained that the Hindu association was accepted on the basis of the reference in Aini-Akbari, and that the resulting verdict was just like the Ayodhya verdict where access was given to both communities.

The Partition of India following Independence changed the power situation drastically, as the Muslim population migrated to Pakistan, and Hindu Punjabis moving in to the town. Leveraging this, a Kund Committee was formulated and a Constitution was written in 1948, proclaiming the site as a Hindu Teerth Sthal and restricting access for Muslims. According to the Constitution, the name of the committee was stated as Shri Shiv Kumbh Sakamjati Agarmars/(sh)an Prakash Sabha Sohna. The name itself suggests the acceptance of this being a Hindu entity, capitalising on associations with the deity Shiv, its position as a place of pilgrimage and references to the saint Sakhamjati, who is also identified as the hot spring in a personified form. It is not clear how and when these associations crept in between the 17th and the 20th century. It is possible that the significance of the site as a place of pilgrimage that was documented in the 16th century was overlaid with it being envisioned as the sacred river Ganga12 at Varanasi, leading to the construction of the Shiv Temple. As per contemporary local knowledge, Sakhamjati is said to be derived from the name of the spiritual guide of the Banjara who is said to have built the domed structure over the hot spring. This version of the story is in contestation with the story documented in the 1884 District Gazetteer that mentioned a faqir who lived here and blessed the Banjara, enabling him and his cattle of 100,000 strength to quench their thirst. One resident narrated that Sakhamjati was a saint, who had two brothers Balamjati and Biramjati. This overlay of the saint’s name onto the site is difficult to date.

There is a distinction between the approach of the people who have been living in the town for many generations versus those who have come in post Partition. In the Rajput and Mahajan families who have lived in Sohna over generations, the cycle of birth, marriage and death of the local residents is inseparably associated with the Kund, as after the birth of a child, he/she is bathed here for the first time. A dhwaja (flag) accompanies the bride in Mahajan families, which is hoisted at the finial of the Kund and upon someone’s death, the last rites are performed only once the body is bathed using water drawn from the Kund13.

The Constitution lays down objectives for the Sabha and formation of Organisation Committee under it. The appropriation was now complete, with any secular or shared past being erased from the narratives being told. The Committee boasts of being a democratic organisation, following its Constitution and representing all communities except the Muslims. This is a negotiation of cultural or symbolic value, to include a ‘cultural affiliation in the present’ that can be ‘historical, political, ethnic, or related to other means of living together’ (De la Torre 2002, p. 11).

The Committee maintains the site and manages the revenue generated as a fee is charged for taking a dip, booking a room for bathing or staying in the guest houses. The Kund has seen a consistent flow of resources in the past, as individual donors contributed to the building activity, with stone plaques mentioning the details clad across the floor and wall surfaces. At present, the Committee generates enough revenue to pay the salary of 13 employees engaged in cleaning, handling ticket sales, clerical work and overall management of the site. For any additional construction activity, funds are collected from the influential residents or outsiders who may have political or associational ties with the site.

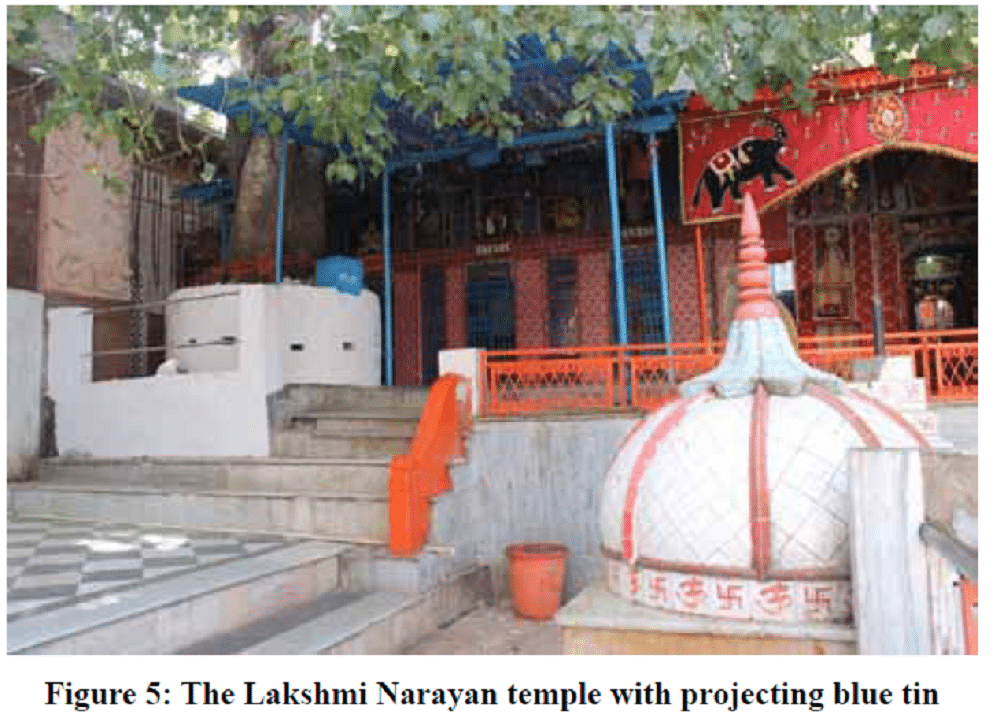

The entire complex is managed as a whole by the Kund Committee, but decision making with respect to the individual parts is divided between the Kund, Shiv Mandir, Lakshmi Narayan Bhole Shankar Mandir, Hanuman Mandir and Arya Samaj Mandir. The Shiv and the Lakshmi Narayan Bhole Shankar temples are under custodianship that passes from generation to generation.

Use in past and present

The water of the spring was tested in October 1863 as a satisfactory cure for Delhi ulcers and again in February 1872, by Dr. Charles Smith who investigated the spring water as a cure for rheumatism, and recommended the setting up of a sanitarium (Punjab Government 1884, p. 14-16). In the report of Dr. Smith, as many as 250 people are said to take a bath at the same time during melas (fairs), hence the religious association was noted but it was not referred to as ‘Shiv Kund’ (ibid., p. 14). A travelogue by David Ross, who passed through Haryana in 1870s discussed the hot sulphuric springs with medicinal virtues that were tested and vouched for by English physicians. He documented the spring as being frequented by rheumatic invalids, sufferers from skin and blood diseases and Delhi sores from distant parts who seem to derive benefit bathing and drinking the waters.

The scientific validity of the spring water remains contested till date, with additional challenges such as heavy reduction in the water emanating from the natural spring. In 2001, an earthquake is said to have impacted the natural water source to increase the otherwise diminishing water supply from the point of origin, by atleast double, with the emanating water being of higher temperature than before (Punjab Kesri 2002). In 2002, the issue of depleting water from the spring was discussed at a meeting between the citizens of Sohna and a committee of eight members formulated for the cleaning of source of the natural spring on the premises of the Kund. The proposal of supplementing the water of the spring with water bored at a distance from the original source by the Managing Committee was opposed by the local residents who felt that the significance of the spring would get lost if the natural spring water was supplemented with water bored elsewhere (Amar Ujala Bureau 2002). Following this, government officials took a call to stop drawing water for the Tourist Complex establish on top of the hill from the natural spring (Amar Ujala Bureau n.d.). Bore wells were dug out at the depths of 440 in 2003, 50 metres away from the original source and 600 feet depth in 2008 and submersible pumps installed in these to draw water that feed the original natural source (Ghosh 2009). Mining at Khori Jamalpul and Sirohi as well as ground water extraction are seen as probable reasons for the reduced water outflow of the spring.

According to the Ward Councillor, the District Public Health Engineering Department dug borewells for water supply to the residents. The bored water supplied to the households is hot and needs to be cooled before being used for any purpose. The justification of this comes from the study by Deb and Ray (1971, p. 369) who had calculated the spread of the geothermal field to an area of about 42,000 sq ft. They also compared the water from the spring with water from a tubewell dug north of the spring and found the chemical composition to be very similar. The SO4 content of spring water was 11.5 ppm while that of the tubewell was 10.5 pm.

The residents equate the hot water with the water of the hot spring and are also concerned about the negative impact of the high mineral content in the form of kidney stones etc., when used as potable water. As per the Ward Councillor, a proposal for canal water supply is underway, with storage being developed at village Ghamroj nearby. The presence of Sulphur in the water of the spring has been another contested issue. While the local population and managing committee are convinced about the medicinal property of the water and the presence of sulphur in the water that contributes to its properties, there have been studies conducted by institutions that confirmed the lack of sulphur in the water of the spring and served as the argument to support extracting ground water and supplying to the town.

There is a clear divide in the attitude of people who live within the zone where ground water is hot and sulphurous vs the residents who live beyond this zone and visitors from outside Sohna. The ones who get hot sulphur water in their homes believe that the water is the same as that in the Kund14, hence reducing their visitation for bathing purposes. Some of those who live beyond the zone still use it for bathing for medicinal and practical reasons while those who visit from beyond Sohna fervently believe in the medicinal and religious significance of the Kund, an attribute that facilitates the economy around the Kund.

The springs have been appropriated by Hindus and associated with religious values over time, named as Shiv Kund with a Shiva temple established within the complex. It receives huge number of visitors for the medicinal value of the springs and for the religious associations, integrated with the lunar calendar marking specific sacred days when the significance of taking a dip in the waters becomes even higher. During winter months, per day visitation at the Kund was noted as about 3000 to 4000 in 2009 (Ghosh 2009) and is 8000 to 10000 according to the Manager of the Kund over the recent years. The annual Ganga Snan Mela held on Kartik Poornima that falls a fortnight after Diwali is significant for bathers who flock in large numbers at the particular date. About a lakh visitors are said to have taken a bath at the Kund during Ganga Snan in 2001 (Dainik Bhaskar Correspondent 2002), though the number may be closer to 25,000 according to the person on the ticket counter and Kund Manager15. Somvati Mavas, a no moon day falling on Monday that occurs twice or thrice per year and Dhulendi are days when the visitations to the Kund rise considerably. The increased numbers on Dhulendi are of visitors who are returning from a mela (fair) held annually in Milakpur at Samadhi of Baba Mohan Ram about 29 Kms away from Sohna. People who go for the mela also visit the Shiv Kund.

Another segment of visitors are those who come to see Prem Bhagat ji, famed for treating illnesses by pressing veins. He treats 200-500 people per day during the morning and evening hours and such visitors also come and take a bath at the Kund. Hence, the visitors can be categorised on the basis of the intent for visit:

● Treatment of skin or bone diseases

● Taking a dip in the Kund on sacred days such as Ganga Snan, Somvati Mavas and Makar Sankranti

● Taking a dip after visiting Milakpur Mela or Prem Bhagat ji

● Saints invited to attend conference on annual memorial of Baba Lal Das in January The local residents use the site in many ways on different occasions:

● Sewa for bhandara (sponsored community feast for religious purpose) on Baba Lal Das Jayanti annually

● Individual and collective worshipping on Makar Sankranti, Ganga Snan, amavas (no moon day) and poornmasi (full moon day), navratras (sacred nine days occurring twice in a year)

● Week long Hanuman Jayanti celebration with bhajan-kirtan (singing devotional songs) and bhandara

● Janmashtami celebrations with redecoration of all individual temples, preparation of tableaus, competition of breaking of pot etc. All town residents participate.

● Full day kirtan by Mahila Mandal, a week after Janmasthami, in the week leading to Radha Ashtami.

● Bathing on a daily basis and when there is no water supply

● Bhandara on every Saturday for Shani Devta, a trend started two to three years ago.

● Annakoot celebration with contribution from all temples within the complex

● Kirtan at Shiv Mandir on all nine days of Navratras

● Bhandara on Ramnavmi by particular local business family dealing in gold and silver and property

● Birth, wedding and death in families that belong to the town from many generations

● Arya Samaj Yagya on every weekend and other programmes.

● Daily prayers by respective custodians of each temple in mornings and evenings, with staggered timings for Arya Samaj Mandir, Shiv Mandir, Lakshmi Narayan temple and Hanuman Mandir

● Worshipping the Peepal tree

● Kund Committee elections and meetings

The outsider, insider and potential stakeholder discussion here is interesting, and opposed to the model of conservation planning and decision making, where those with the ‘right and might’ are identified as public officials, bureaucrats, policy makers, those who influence them and conservation professionals and other experts invited into the process (De la Torre 2002, p. 17). Public officials, bureaucrats, policy makers and conservation professionals or experts are infact outsiders to the decision making process, while potential stakeholders in the form of people originally from Sohna who still come back for rituals related to life events, potential beneficiaries, experts and future generations. Insiders include the Kund Committee, influential Hindu or Arya Samaji residents and custodians of the four main temples within the site. They have the right and the might of decision making in terms of using the site, contributing to the site and benefiting from it. The visitors also impact decision making, as the Committee is driven towards maintaining value for them, them being the source of income through bathing ticket sales.

Values or significance

The aesthetic value as seen by the art historian or conservation specialist is embodied in the stylistic components from the past. The local residents, users and visitors, on the other hand, value the present condition of the site that is clean and beautiful now, due to the interventions made over the last decade or two.

The life of the site in the present day is embodied in the use patterns to a large extent. The activities can be grouped into annual festival celebrations associated with different deities and temples, to include prayers and food distribution, weekly activities, marking of life events16 and secular activities of Kund Management. These and visitation by people from outside the town represent social and religious/spiritual values, along with cultural/symbolic values. Hence, use value that is seen as a part of economic values by Mason (De la Torre 2002, p. 12) needs to be differentiated from the patterns of use that demonstrate multiple sociocultural values. The act of bathing at the site everyday by quite a few male local residents is a more mundane activity, though it does contribute to a place identity. The question are: is there is a need for the category ‘use value’ as theorised by Alois Reigl, should use be seen as a source of sociocultural values, or only included as a type of economic value as per the Getty Conservation Institute model (De la Torre 2002).

There are other sociocultural values listed by Mason (De la Torre 2002, p. 12); namely, social and spiritual or religious that are identifiable in the case of the Shiv Kund, and at the same time reflect contestations. Does ‘use value’ as identified by Reigl (Stanley-Price, Talley & Melucco 1996, p. 80) need to be identified as a separate value is another point of discussion? These values are based on extrinsic factors primarily, though the medicinal property of the hot sulphur water emanating from the spring is intrinsic, overlaid with a religious/spiritual meaning, both for people who get treated of diseases upon bathing here or those who visit the site as a sacred place and take holy dips in the water. The natural property of the water that heals those suffering from skin diseases and rheumatism is a major value driver. It also receives huge number of visitors for religious purposes, integrated with the lunar calendar marking specific sacred days when the significance of taking a dip in the waters becomes even higher. The value or significance that the site packs for the local community and other involved stakeholders has ensured its continuity as a place of visitation for religious, health and other social reasons. It is this value that needs to be showcased and leveraged to attract a larger group of visitors to the complex and to Sohna in general.

Key findings and recommendations

The Shiv Kund at Sohna presents a case of living sites in India that are valued and maintained by local stakeholders, without support from the state or experts. The heritage, though not termed as such by the direct stakeholders, has been constructed through a selective narration of history, added layers of social and religious significance and continuous use/re-use and maintenance of the site. Intrinsic factors embedded in the built form and spring water hold stronger relevance for the experts as sources of information about the past than for the custodians, residents and visitors, who associate with the extrinsic factors.

The complex is a thriving and successful socio-religious and economic landmark and the consistent additions reflect the sense of belonging that the local and the larger community for whom it holds significance, invest in the place.

It is quite apparent that the site represents an amazing opportunity to build tourism visitation at the site, resulting in the economic benefits. There will be implications for the local and state governments to build/enhance infrastructure and service elements that will enable the site to build carry capacity and prevent adverse impacts to a large extent. The opportunity that this case has presented has implications for the larger approach and tourism policy at a state and national level, wherein a strong focus on sites of such heritage value in the smaller town spread over the country can bring them on the visitation map for our large domestic base and potentially even international travellers.

The key recommendations:

1. Bring focus on smaller towns and cities and the heritage they represent in the forms of sites and the cultural dimensions.

2. Position and market these sites and locations through a narrative that draws from their heritage and use value dimensions.

3. Invest in infrastructure, services enhancements that allow the capacity building to take place in advance of visitation numbers growing.

4. Connect with the key stakeholders to draw from their influence and custodianship.

5. The economic benefits from tourist visitation and spending can be deployed by the stakeholders and custodians in ensuring a superior conservation of our built heritage that resides in our small towns and cities.

END NOTE

1. Now Masjid School

2. This was a part of the tourism development initiative of the State of Haryana. 42 resorts have been set up by the state tourism department along highways or at tourist destinations, spread across 19 districts of Haryana. Named after names of birds, these are run by Haryana Tourism Corporation Ltd.(Haryana Tourism 2017)

3. Sohna, spelt as Suhnah and Sahnah was a parganah of Rewari Sarkar in Delhi Subah (Jarrett 1891, p. 105). Suhnah was also listed as one of the 11 Mahals of Rewari Sarkar, encompassing 251,738 bighas of land, dominated by Rajput Tathar caste

4. One documented in the Gazetteer of the Gurgaon District, 1883-84 (Punjab Government 1884) and another as told by the locals at present

5. Municipal Committee till 2014 with 15 wards

6. A plaque on the western verandah, announces that this dharmshala (rest house) was built by Jaipur resident Seth Harnandrai, Gulabrai Khaitan in Samvat 1714 for Hindu visitors who come to Shri Shiv Kund. The date corresponds to 1657 AD

7. The merchandise is identified as salt in the story narrated by the Kund Mahant, This is a possibility, as salt was manufactured in the Sultanpur region till the end of 19th century

8. The earliest textual description of the site is from the 16th century AD. There is no available evidence or local narrative that goes back 850 years

9. No evidence of any such increase in visitation to the site due to the tourist resort being set up by the government. The resort is in a poor state of maintenance at present, used essentially by elected politicians and state level bureaucrats. It is unpopular among local residents and tourists

10. The rulers of Udaipur were known by the title of Rana and the only Sisodias associated with the site are those from Jalandhar, not Udaipur. Textual sources have referred to the Sisodias from Jalandhar or Jat rulers as the builders of the fort

11. There is no evidence of any of the temples being pre 15th century. The stories about the origin of the site also revolve around the hot spring and not the temples. The built form analysis also establishes the hot spring as being the central point and not the temples

12. People are known to flock to the site for fairs in the 19th century

13. Based on interview with the manager of the Kund Shri Rajesh Raghav and Treasurer of the Committee Lalit Jindal

14. The proposal of supplementing the water of the spring with water bored at a distance from the original source by the Managing Committee was opposed by the local residents who felt that the significance of the spring would get lost if the natural spring water was supplemented with water bored elsewhere (Amar Ujala Bureau 2002). The Committee decided to bore and supplement despite the opposition, contributing to the diminished value of the water for the involved residents

15. Visitation goes up in the range of 20,000 to 30,000 per day on these occasions according to the Manager Shri Rajesh Raghav

16. The cycle of birth, marriage and death of the local residents is inseparably associated with the Kund, as after the birth of a child, he/she is bathed here for the first time. A dhwaja (flag) accompanies the bride in Mahajan families, which is hoisted at the finial of the Kund and upon someone’s death, the last rites are performed only once the body is bathed using water drawn from the Kund

REFERENCES

A.I.I.S. (2017) ‘Home/Collection’ (online) (cited 3 April 2017). Available from <http:// vmis.in/ArchiveCategories/collections?search=sohna>.

Amar Ujala Bureau (2002) ‘Jal stroton ki kami par baithak aaropon tak simti’, Amar Ujala, 2 December.

Amar Ujala Bureau (2004) ‘Controversy on the presence of sulphur in shivkund’s water’, Amar Ujala, 14 October.

Behl, A. (2012) ‘INTACH Live History’, Friday Gurgaon. (online) (cited 2 January 2015). Available from <http://fridaygurgaon.com/news/821-intach-live-history.html>.

Bhoria, K.S. and Bajaj, B.R. (1983) Haryana District Gazetteers: Gurgaon, Chandigarh, Haryana Gazetteers Organisation, Revenue Department.

Channing, F.C. (1882) Land Revenue Settlement of the Gurgaon District, Chandigarh, Punjab Government Press.

Dainik Bhaskar Correspondent (2002) ‘Sohna mein shraddhaluon ne kiya garm pani ke chashme mein snan’, Dainik Bhaskar, 19 November 19.

Dainik Bhaskar Correspondent (n.d.) ‘Shiv Kund Committee Pradhan Chunav ki maang anuchit: Singh’, Dainik Bhaskar, 13 June.

De la Torre, M. (ed) (2002) Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage: Research Report, Los Angeles, CA, Getty Conservation Institute.

Deb, S. and Ray, D.K. (1971) ‘Study on the origin of Sohna thermal spring in Gurgaon District, Haryana’, Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy, 37: 5, pp. 364-378.

Directorate of Archaeology & Museums (n.d.a) ‘Introduction’, Government of Haryana (online) (cited 23 May 2017). Available from <http://archaeologyharyana.nic.in/arc1. html>.

Directorate of Archaeology & Museums (n.d.b) ‘Introduction’, Government of Haryana. (online) (cited 23 May 2017). Available from <http://archaeologyharyana.nic.in/arc3. html>.

Directorate of Census Operations (2011) District Census Handbook Gurgaon: Village and Town Directory, Chandigarh, Directorate of Census Operations, Haryana.

Directorate of Census Operations (2011) District Census Handbook: Gurgaon, Chandigarh, Directorate of Census Operations, Haryana. District Administration, Gurgaon (2014) District Gurgaon: Tourist Places. (online) (cited 26 October 2014). Available from < http://www.archive.india.gov.in/outerwin. php?id=http://gurgaon.nic.in>.

Fennell, D.A. (2010) Tourism Ethics, New Delhi, Viva Books Private Limited. Ghosh, A. (2009) ‘Water level falls at Sohna, needs pumps’, The Times of India. (online) (cited November 3, 2016). Available from <http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/ delhi/Water-level-falls-at-Sohna-needs-umps/articleshow/4197302.cms>.

Haryana Tourism (2017) Tourism Hubs, Haryana Tourism. (online) (cited 30 August 2017). Available from <http://haryanatourism.gov.in/showpage. aspx?contentid=5026#hub>.

INTACH (1994) Guidelines for Completing the INTACH Inventory of Historic Buildings, New Delhi, INTACH.

INTACH (2004) Charter for the Conservation of Unprotected Architectural Heritage and Sites in India, New Delhi, INTACH.

INTACH (2014) Field Book for Listing of Built Heritage, New Delhi, INTACH.

Jain, S. and Dandona, B. (eds) (2012) Haryana: Cultural Heritage Guide, New Delhi, INTACH and Aryan Books International.

Jain, S. (2012) ‘Mapping Haryana’s built heritage: Historic cities and architectural typologies’, Haryana: Cultural Heritage Guide, New Delhi, INTACH and Aryan Books International, pp. 37-48.

Jain, S., Munjal, P.G. and Arora, V. (2016), The Future of Historic Cities: Urban Heritage in Asia, New Delhi and Gurgaon, Aryan Books International, DRONAH.

Jarrett, H.S. (trans) (1891), Ain I Akbari by Abul Fazl Allami, Vol. II, Calcutta, Asiatic Society of Bengal.

Khandelwal, K.K. and Maitrey, M. (2010) Haryana: Lok Sanskriti ke Kharokhe Se, New Delhi, S. Chand and Co. Ltd.

Mishra, D.K. (n.d.) ‘Wrong perception – Sulphur in the Kund cures diseases’, 11 December, Gurgaon.

Munjal, P.G. and Srivastava, P. (2013), ‘City Development Planning in Mandu: Evolving city conservation and management strategy’, Context: Built, Living and Natural, 10: 2, pp. 149-156.

Munjal, P.G. (2015) ‘The potential of a participatory approach in sustaining the fairs and festivals of small towns: The case of Sohna, Haryana’, Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 7:4, pp. 347-366.

Munjal, P.G. (2017) ‘Construction of Heritage: Small and Medium Towns of Gurgaon District’, Journal of Heritage Management, 1:2, pp. 98-125.

Planning Commission (2009), Haryana Development Report, New Delhi, Government of India.

Price, N.S., Talley Jr., M.K. and Vaccaro, A.M. (eds) (1996) Historical and Philosophical Issues in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, Los Angeles, The Getty Conservation Institute.

Punjab Government (1884) Gazetteer of the Gurgaon District, 1883-84, Lahore, Punjab Government.

Punjab Government (1910) Punjab District Gazetteer, Vol. IV A: Gurgaon District, Lahore, Punjab Government.

Sharma, G.K. (2011) ‘Shiv Kund – Sohna (Gurgaon)’, Meri Duniya., 7 March. (online blog post) (cited 21 August 2016). Available from <http://gkonweb.blogspot.in/search/label/Shiv%20Kund%20Sohna>.

Stanley-Price, N., Talley, M. K. and Melucco, V.A. (eds) (1996) Historical and philosophical issues in the conservation of cultural heritage, Los Angeles, Getty Conservation Institute.

T.C.P.D. (2012a) Draft Development Plan-2031 AD for Farukhnagar, Chandigarh, Government of Haryana.

T.C.P.D. (2012b), Final Development Plan of Sohna 2031 A.D., Chandigarh, Government of Haryana.

Parul G. Munjal, Associate Professor, Sushant School of Art and Architecture, Ansal University, Gurugram, India.

Sandeep Munjal, Director, Vedatya Institute, Gurugram, India.

Email: sandeep.munjal@vedatya.ac.in