Hospitality Internship Placements: Analysis For United Kingdom And India

Internships form an important aspect of the graduate/undergraduate programmes. They are instrumental in formulating the key competencies required by the graduates at the time of final placements. Internships are imperative in mapping the personal characteristics of the student’s vis-à-vis the requirements of the industry and give them a feel about the working conditions. This paper aims to investigate the experience of the interns and compare it with their expectations and highlights how smoothly they can be transformed into hospitality professionals. This is done with the help of the ServQual instrument applied for the internship program for students undergoing training in India and United Kingdom. The factors impacting the internship for the students are highlighted with the help of factor analysis and recommendations for the industry and academia are highlighted.

INTRODUCTION

Hospitality internships provide an experience that is said to benefit all concerned – the students, industry and the college. The importance of internships in developing the students professionally and personally is well documented (Leslie, 1991; Gillin et al., 1984 and Williams et al., 1993 cited in Waryszak, 1999; Kok, 2000 Arif 2007). In India there are many schools and institutions offering diploma /degree / master programmes in hospitality. Most of them are recognized from the government while others are affiliated to foreign institutions. The curriculum of most of the institutes provides opportunities given to hospitality students while carrying out a full time academic course to get introduced to real life situations which help in making them successful professionals in the future. These placements can be prearranged by colleges either in India or abroad.

The Indian economy, witnessing phenomenal growth since the last decade, would continue to be the second fastest growing economy in the world despite the current global financial crisis. The sound performance in each segment (agriculture, industry and services) is leading to this healthy growth (Indian Brand equity foundation, 2009). Services continue to be the major contributor to the Indian GDP at 53%. Globally they form 69% of the GDP (World Development indicators 2007 cited in Aiyar, 2009) and the tourism and hospitality industry contributes 9.8% to the global GDP. This is expected to rise to 10.38% of the GDP by 2010 (Cygnus, 2007). The worldwide employment within the tourism economy is expected to grow to 251.6 million jobs by then. (International Labour organization, 2008).According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization, tourism will act as the key global driver to come out of the recession (Travel Biz Monitor.com, 2008). Thus this continues to be a growing sector in fields of employment. It is, therefore, imperative for the universities concerned to churn out students that are aligned to the industry demands. Internships can be the locus in shaping the students. Internship is vital for developing novices and gaining an insight into the requirements of the sector. It is quite important in shaping the individual vis-à-vis the industry but the process should not be a horrendous experience for the students. If internships are not planned by institutions in consultation with industry then students often face difficulties. They usually end up doing entry level jobs which ultimately become monotonous resulting in demystifying the job (Neuman and Banghart, 2001) and diverts the opinion and interest to non-hospitality industries. These wrong signals are a result of improper planning and have raised concerns among all the parties involved because word-of-mouth spreads faster and might affect demands in future. It is, therefore, important to properly plan, control and assess the internships (Mc Mohan and Quinn, 1995). The internship programmes, thus, have to be structured by meeting the needs of both educators and industry (Downey and De Veau, 1987) and work as “consulternships” (Neumann and Banghart, 2001). Our study will highlight the gaps between expectations and perceptions of interns giving an insight into whether these differ across domestic and international internship experiences.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Internships, industrial exposure, supervised work experience (SWE) are opportunities given to hospitality students while carrying out a full time academic course to get introduced to real life situations which helps in making them successful professionals in the future. For a hotel graduate, hospitality internship acts as an association between university Journal of Services Research, Volume 10, Number 1 (April – September 2010) 87 Singh, Dutta education and industry expectations. Though site visits and guest speakers from industry can create the atmosphere but internships do provide ground realties on the areas they have been studying and listening from experts (Domask, 2007). SWE gives them opportunity and freedom to discuss their progress, problems and academic requirements which basically aims to relate their learning’s with management practices ultimately leading to self realization and development. The employer acknowledges an employment relationship between the business and the learner. They are not replacing regular employees but learning under their close supervision. The students are not always necessarily entitled to a job at the conclusion of training. Waryszak (1999) agrees that employment know-how through internships helps in induction which ultimately increases the performance and retention of manpower.

Various studies outline the benefits enjoyed by interns including an opportunity to grow up, networking with potential employers, learn new concepts, gain experience, growth opportunities, improved self confidence personality and skills development according to demands of the industry (Collins 2001, David Leslie, 1991). Furthermore interns have more focused approach towards their careers since they already have the right exposure in the industry and most importantly to assess whether they have made the right choice. After internship they are able to relate their experiences with the theory taught in the Institution. King and Waryszak (2003) confirmed that internship placements were important in attaining their current job. But we all have experienced and realized that this feeling and realization is not uniform among all interns.

The difference between intern’s expectations and perceptions regarding rewards, job satisfaction is influenced both by the educational institution and the manner in which the industry treats the interns (Barron and Maxwell, 1993). Hospitality Industry is suffering from a manpower crunch. According to a research carried out by Associated Chambers of Commerce & Industry of India (ASSOCHAM), the industry is expected to witness an attrition rate of as high as fifty per cent in the next two years (Express Hospitality, 2008). The industry has faced difficulties in training and retaining employees that deliver the same quality which industry expects (Barron, 2008). It is also observed that

this attrition is more for lower management levels because most of the students after working in the industry for first few years get attracted to other industries. Jenkins (2001) has cited Barron and Maxwell (1993): “the more exposure a student has to the hospitality industry, the less commitment he/she demonstrates”. Students desire to join this industry is withdrawing marginally every year. Students are more inclined by the experience they had on their internship and this might prevent them to stay in industry for long (Waryszak, 1999; Mc Mohan and Quinn, 1995). Barron (2008) feels that responsibility lies with the educator to lessen the gap regarding expectations of students towards working life of the industry.

There is certainly an imbalance in the expectations perceived by students of hotel school and what the industry expects from these interns in their internship programme. The internship programmes have to be structured by meeting the needs of both educators and industry (Downey and De Veau, 1987) and work as “consulternships” (Neumann and Banghart, 2001). One issue which seems to bother internship students is compensation and onetary rewards (Srivastava, 2007). Zopiatis (2007) has recommended in his study that educators and Industry Professionals should have pragmatic approach towards internship compensation. Interns were also said to face problems while relating and applying theory in pragmatic situations and managers were not supportive enough to plan their programme (Lamm and Ching 2007). Walo’s (2000) research was quite positive where students have gained managerial competencies after the internship programme.

Zopitatis and Constanti (2007) highlighted five gaps in the hospitality education-industry relationship. This paper explores the gap which focuses on the gap between the student’s academic experience and expectations vis-à-vis their actual experience giving an insight into whether these differ across domestic and international internship experiences. The questionnaire plans to explore this with the help of service quality parameters (Kandampully, 2001). This paper has identified the expectations using each element of ServQual, analyzed the perception formed during placements both in UK and India; evaluated the importance of placements by analyzing and assessing each elements and its priorities from the students perspective.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The data was collected with the help of an instrument – a structured, non disguised questionnaire. The items are related to the interns’ expectations and perceptions resulting to overall satisfaction. There are 28 variables to judge the respective internship expectation and perception based on each element of the ServQual. The first section of the questionnaire consisted of two subsections. Subsection one focused on the interns’ expectations and sub section two focused on their perceptions (postinternship). Both these sections had 4 variables on tangibility, 4 on reliability, 4 on responsiveness, 8 on assurance, 8 on empathy and one question related to the overall satisfaction. Personal interviews were used to avoid any ambiguity. Questionnaires were collected across two universities – one foreign, which also provided internships in UK, and another Indian university which provided internships in India. The students had filled the expectations before starting their internship in the year 2007 and shared their perception after they returned from their programme in the year 2008. The questionnaires collected for the Indian institute were fifty six in number and those collected for the foreign university were sixty in number. The feelings of the respondents were captured on a 5 point Likert-type scale varying from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The second part of the questionnaire dealt with the demographic variables and general information about students such as name of the institution, age, internship duration, location and gender. SPSS Software was used for performing quantitative analysis.

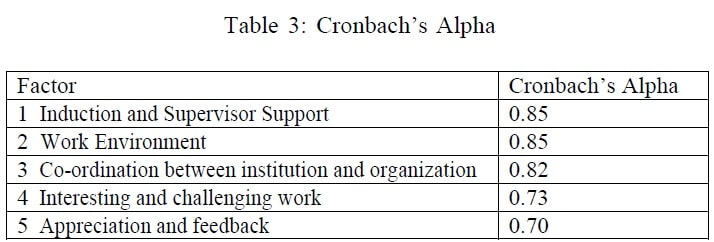

Factor analysis was done to highlight factors impacting the hospitality internships. A measure f construct reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) was computed for each dimension to assess the reliability of the set of items forming that dimension (see table 3). Cronbach’s alpha measures how well the variables measure a single unidimensional latent construct. Technically speaking, Cronbach’s alpha is not a statistical test – it is a coefficient of reliability for the factors derived. A service quality gap calculation was done by finding the gap between the expectations and perceptions of the students prior to and after they came back from their internships.

FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

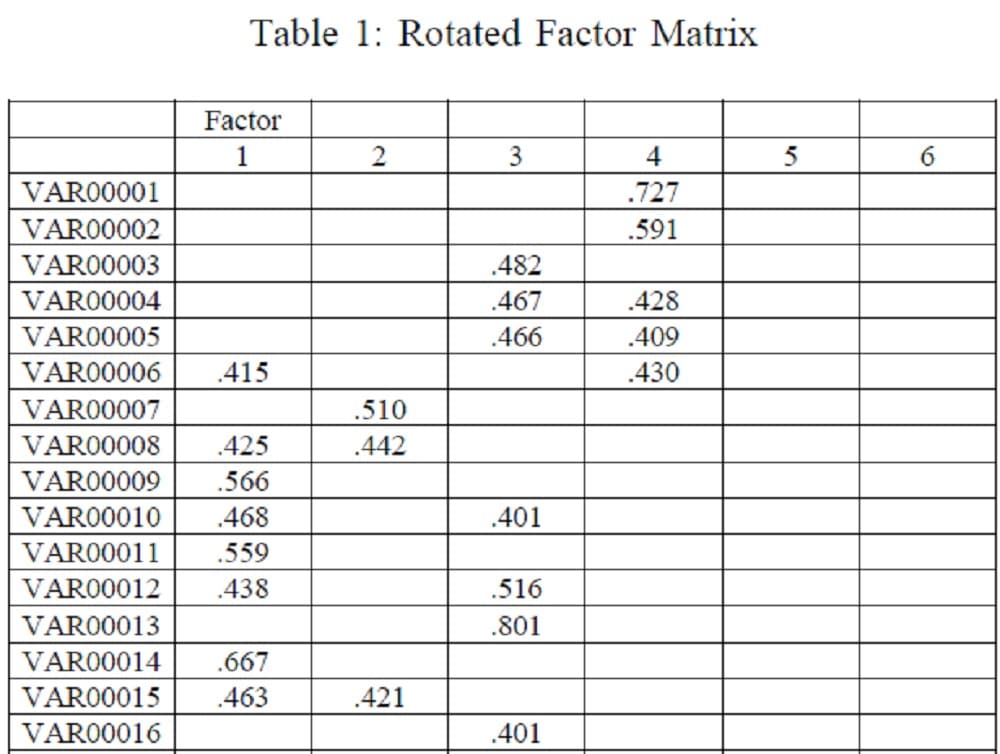

Factor analysis was performed to identify the key dimensions and respondent ratings were subject to principal axis factoring with varimax rotation to reduce potential multicollinearity among the items and to improve reliability on the data (see table 1: Rotated Factor Matrix). Varimax rotation (with Kaiser Normalization) was converged in twelve iterations. Twenty eight items were reduced to six orthogonal factor dimensions which explained 55.7% of the overall variance indicating that the variance of original values was well captured by these six factors.

a Rotation converged in 12 iterations.

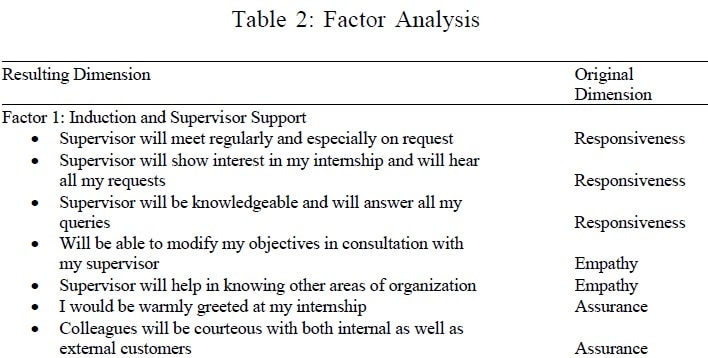

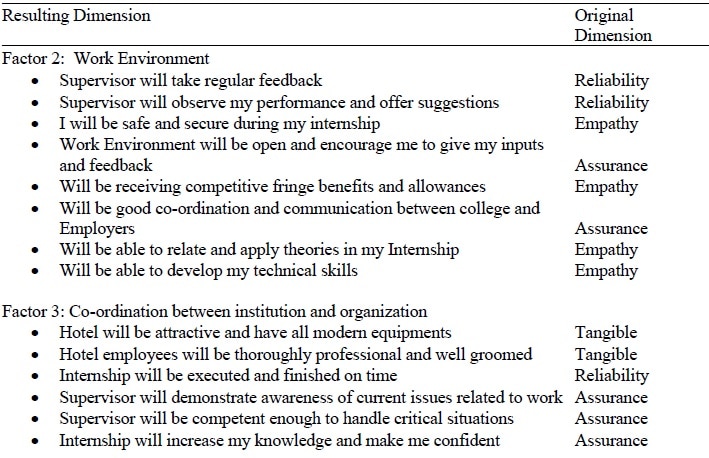

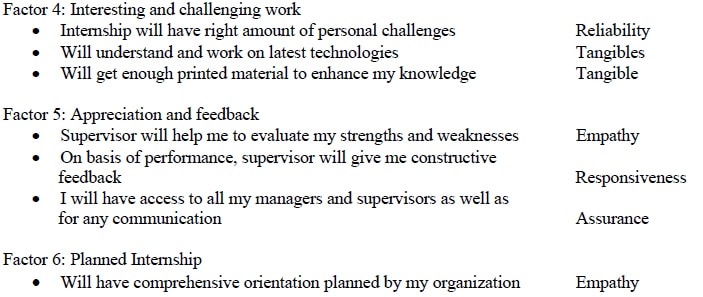

The six factors arrived at are highlighted in table 2. Induction and supervisor support is considered as the most important factor by the students. This being a first exposure for majority of the Indian students with the industry, the students look forward to the guidance of the supervisor and also look up to him as the ‘know all’ who is going to solve their problems. The work environment plays the next major influence and the students expect to be guided well throughout the internship with regular feedbacks and suggestions from the supervisor. The students enthusiastically want to put their learnings from the classroom into practice and develop their technical skills also. The third most important factor is the coordination between the college and the organization. This includes the execution of internship on time, the awareness of the supervisor towards the current issues related to work and their competency to handle critical situation as students are taught that as future managers these roles are expected from them and they look for this coordination between what is taught and what is practiced.

The fourth most important factor affecting the hospitality internships is that the internship should be interesting and challenging. This includes that internship will have right amount of personal challenges; the students will understand and work on latest technologies and they will get enough printed material to enhance their knowledge. The last factor is appreciation and feedback. The interns feel that supervisor will help them to evaluate their strengths and weaknesses and on the basis of performance will give them constructive feedback. The interns also want to have access to all managers and supervisors as well for any communication. The sixth factor highlights that interns look for planned Internship with comprehensive orientation planned for by the organization.

RELIABILITY TEST

The factors have been variably loaded and out of the six relevant factors five were studied for reliability. The five factors were found to be highly reliable with a varying from 0.85 to 0.70. As a rule a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.70 or more represent satisfactory reliability

for the items measured. Thus the items measuring the dimensions

appear to be sufficiently reliable (see table 3).

SERVICE QUALITY GAP ANALYSIS

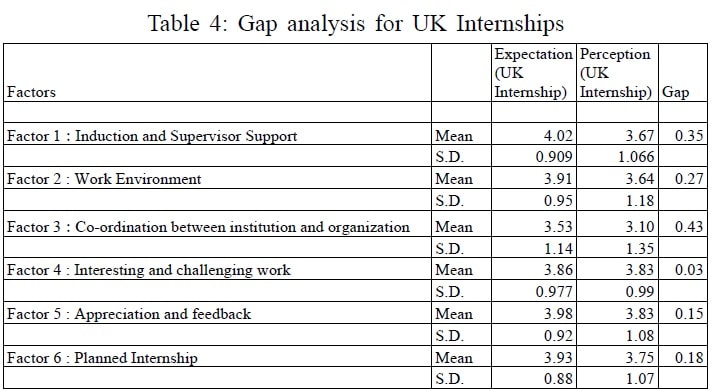

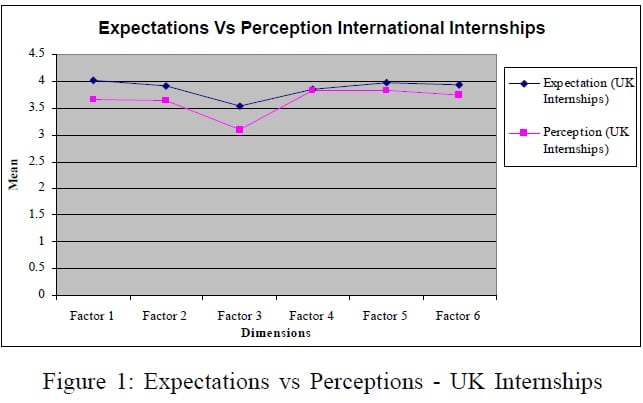

As seen in Table 4 and figure 1 there is a slight difference between the students’ expectations and perceptions egarding internship. Even though the gap is less as compared to doing internship in India but difference is higher for the first three factors as compared to the fourth, fifth and sixth. Thus, for students pursuing their internships abroad it was felt that they required more induction and supervisory support. It is necessary to highlight here that many of the students had ventured out of India for the first time and needed extra support as regards their accommodation and the use of public transport. As the environment is entirely new they seek more support from the supervisor and want to meet them regularly and specially on request. Interns also have their specific areas of interest and they seek to modify their objectives according to these areas. The other factor showing a gap is the work environment. Students wish to be observed and given regular feedbacks, they want to give suggestions and inputs about their work and want to apply the theories, which they have learnt in their classrooms in real life situations. The highest gap is for the third factor ‘coordination between institution and organization’. The interns feel that the ‘foreign’ hotels should have all the modern equipments and the employees should be well groomed and professional. They also feel that the internship should be executed on time and would increase their knowledge and make them confident.

The fourth factor ‘interesting and challenging work’ showed the least gap. This is because the students were given managerial roles and they felt it was challenging as they had to work in tandem with the employees. This excited them as they felt that the job was important for the organization and they were doing some value addition. The managers appreciated them and the students were provided feedbacks so that they knew what their weaknesses were and where to improve upon. A task well done was appreciated publicly and this further motivated the students. Best employees of the month were announced and it was a matter of pride for the students to be nominated for the same.

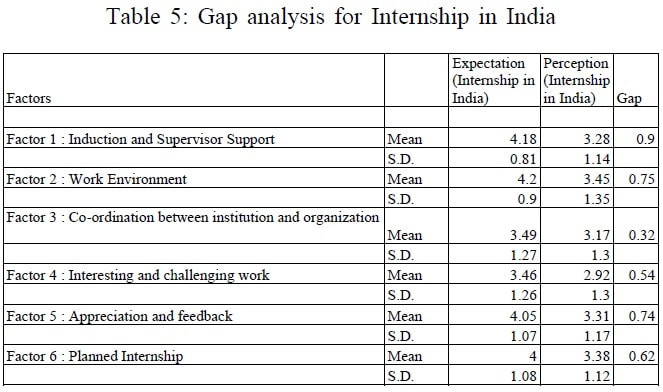

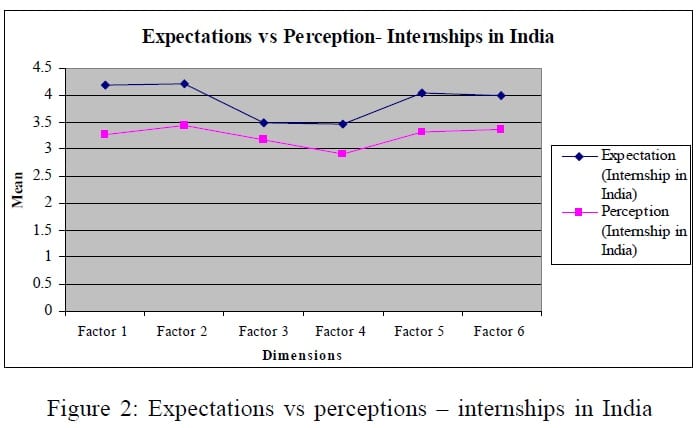

As seen in table 5 and figure 2 there is considerable difference between the student’s expectations and perception regarding internships in India and the gap appears to be consistent throughout. The gap is the highest for induction and supervisor support. In the Indian context, it was observed that the students were not seeking extra support as in the case of foreign interns. The interns were not met with regularly and the supervisor hardly showed interest or had the time to answer their questions. Furthermore, interns were not encouraged to ask questions and modification in the objectives was a taboo. The second factor also showed a high gap with the interns feeling that supervisors were not taking regular feedback or offering suggestions for improvement of performance. The fringe benefits and allowances were other major concerns of the interns. The development of technical skills was also a matter of concern as the interns don’t receive any structured job assignments from their organisations. Very often interns start from entry level assignments which are important to form the foundation but also finish doing menial tasks only which in no way added to their technical skills and leaving them discouraged. Factor five showed the highest gap and the interns felt that the supervisor failed to evaluate their strengths and weaknesses, constructive feedback was not provided and there were communication issues. The internship was not challenging, they did not get a chance to work on the latest technologies or to enhance their knowledge. The interns, thus, felt that their internship was not well planned and the effectiveness was lacking.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

According to the rotated factor matrix “comprehensive orientation planned by the organization” and “supervisor who is competent enough to handle critical situations” are of utmost concern for the students.

From the factor analysis it is clear that induction and supervisor support is important for students for their internships. Support from the supervisor, thus, forms a critical aspect of the training and influences the interns’ perception about the training. Hence, organizations should pay special attention while allocating buddy or supervisor for mentoring the students.

The second gap highlights that proper attention is required from the supervisors so that the learning is constructive and aspirations are met. The hospitality institutions should also communicate realistic expectations about the fringe benefits and allowances offered by the industry. The students placed internationally appear more satisfied with the remuneration as compared to the students trained in India.

The third factor highlights the coordination required between the institute and the organization. This highlights the “consulternships” aspect proposed by Newmann and Bangart (2001).

The fourth factor reiterates the demand for challenging jobs by the interns (Neuman and Banghart, 2001). “Extrinsic monetary rewards become important when the internships purpose and value becomes obscured” (Zopiatis and Constanti, 2007). If we see the hospitality internship scenario in India the students are getting entry level jobs and the monetary rewards are also low, thus, explaining the wider gap between internships in India and in UK.

The fifth factor regarding appreciation and feedback gains relevance in the light of the above discussion. If proper feedback is provided it helps in overall development of the interns. Feedback not only addresses the technical learning which is meant to be achieved but also addresses the competencies required to work like team working, work under pressure, communication skills, grooming etc. Students who are placed in India are facing a huge gap.

The sixth factor highlights the planned internship and probably questions the roles of educationalist and recruiters regarding internship. A frame work has to be developed from both sides to meet the objectives and balance the expectations (Zopiatis, 2007). This gap is quite large for Internships in India as compared to interns placed internationally.

It is seen that the Indian hospitality industry is facing recruitment and retention problems. More than half of all the vacancies in the sector remain unfulfilled. The supply in 2004 was not even touching 40% of the demand. The challenges facing the employees of the hospitality industry in India are unattractive wage packages, long working hours, and harsh working conditions (Cygnus, 2007). These issues affect the supervisors and are easily visible in the working environment which dampens the spirit of the interns to join the industry. As a result there is a growing concern regarding brain drain of hospitality students either to foreign countries or other service sectors. Express Hospitality, 2004 this is also reflected in the scores for overall satisfaction with the internship as the interns placed in UK were agreeing to have had a satisfactory experience with their internship but the Indian interns were non-committal about their experience.

Based on above conclusions, following are the recommendations:

• The work environment should be conducive for learning. Students should receive focused learning which needs to be checked and revised by the mentor on timely basis. The training plan devised by organization should have equal space for learning and interaction with Supervisor.

• The feedback by the supervisors should be linked with the theoretical concepts which are taught in the classrooms. The institutions can help the organization by providing guidelines and parameters. This helps the students and gives them a perspective in terms of their understanding. They can also organize casual meetings with the students to discuss concerns related to their training.

• Organizations should start thinking about offering competitive fringe benefits to motivate the students. Industrial trainees should be included under Minimum Wages Act, 1948. This might increase the sense of ownership towards the organization.

• The network between institution and organization should be well documented and consistent. Both systems need to get involved in planning and execution of training. The involvement enforces the commitment.

• Students’ willingness to learn should be directly related to the right number of challenges and growth planned for him. Training plan should identify the objectives required and expected to be achieved by students so as to avoid getting any surprises. Plan should have all details regarding job rotation, mentor, feedback process, grievance handling etc.

Only two universities based in India and UK were considered for the study. Future studies can be done with large sample size and selecting more hospitality institutions in various countries.

REFERENCES

Aiyar, S S A (2009) ‘Services wont save us from recession’, Economic Times, New Delhi, dated 14th January, 12.

Arif Mohammad (2007) ‘Balridge theory into practice: a generic model’, International Journal of Educational Management, 21:2, 114-125.

Barron and Maxwell (1993) ‘Hospitality management students’ image of the hospitality Industry’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, l 5:5, vviii.

Barron Paul (2008), Education and talent management: implications for the hospitality industry, International Journal of contemporary Hospitality Management, 20:7, 730-742.

Collins, B (2002) ‘Gateway to the Real World: Industrial training; dilemmas and problems’, Tourism Management, 23:1, 93–96.

Cygnus, (2007) Indian Hotel Industry, Cygnus Business Consulting and Research, Hyderabad.

Domask J.Joseph, (2007) ‘Achieving goals in higher education. An experiential approach to sustainiability studies, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education; 8:1, 53-68.

Downey F. James and De Veau T. Linsley (1998) ‘Hospitality Internships- An Industry View’ Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 29:3, 18-20.

Express Hospitality fortnightly insight ‘Confronting the Crunch’ 1-15 June 2008 available from http://www.expresshospitality.com/20080615/hospitalitylife01.shtml.

Express Hospitality fortnightly insight ‘Students Who Want to Excel Need to Understand the Concept of Running a Hotel’ issue dated 24 November 2008 available from http://

www.expresshospitality.com/20041129/peoplepower02.shtml.

Global hospitality insight Ernst and Young available from http://www.hospitalitynet.org/file/

152002487.pdf.

Tourism confornting the economic downturn (online) (cited 9 March, 2009). Available from <http://www.unwto.org/index.php>.

Indian Brand equity foundation (2009), ‘Indian Economy Overview’ (online) (cited 20 January, 2009). Available from <http://ibef.org/artdispview.aspx?in=36&art_id=21255&cat_id=140& page=1>.

International Labour organization (2008), (online) (cited 28 December, 2008). Available from <http://www.ilo.org/public/english/dialogue/sector/techmeet/tmhct01/tmhctr2.htm>.

Jenkins, A.K. (2001) ‘Making a Career of in? Hospitality Students’ Future Perspectives: An Anglo-Dutch study’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 12:1, 13–20.

Kandampully, J; Mok, C. and Sparks, B. (2001) Service Quality Management in Hospitality, Tourism, and Leisure, New York, Haworth Hospitality Press.

King, B.; McKercher, B. and Waryszak, R. (2003) ‘A Comparative Study of Hospitality and Tourism Graduates in Australia and Hong Kong’, The International Journal of Tourism Research, 5:6, 409–420.

Kok, R M (2000) ‘Outside the Box: Creating your own internship opportunities, Journal of Hospitlaity and Tourism Education, 12:3, 21-23.

Lamm and Ching (2007) ‘An Exploratory Study of An Internship Program: The case of Hing Kong students’, Hospitality Management, 26:2, 336-351.

Leslie, David (1991) ‘Hospitality Industry Industrial Placement and Personnel Management’, The Service Industries Journal, 11:1, 63–73.

McMahon, U. and Quinn, U. (1995) ‘Maximizing the Hospitality Management Student Work Placement Experience: A case study’, Education and Training, 37:4, 13–17.

Newmann, B.R. and Banghart, S. (2001) ‘Industry-university “consulternships”: An Implementation Guide’, International Journal of Educational Management, 15:1, 7-11.

Srivastava, N. (2007) ‘Hospitaltiy Internships: Is it really motivating?’, FHRAI Magazine, 7:5, 46-49.

Travel Biz Monitor.com (2008) ‘Tourism Key Driver to Come Out of Recession’, (online) (cited 30 December, 2008). Available from <http://www.travelbizmonitor. com/PrintArticle.aspx?aid=4392&sid=0>.

Walo, M.A. (2000) ‘Contribution of Internship in Developing Industry Relevant Management Competencies in Tourism and Hospitality Graduation’, (Online) (cited 23 December 2008). Available from <URLhttp://epubs.scu.edu.au/theses/48/>.

Waryszak, R.Z. (1999) ‘Students’ Eexpectations from their Cooperative Education Placements in the Hospitality Industry: An international perspective’, Education and Training, 41:1, 33-40.

Zopiatis, A. (2007) Hospitality Internships in Cyprus: A genuine academic experience or a continuing frustration’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 19:1, 65-77.

Anjana Singh is Professor, Vedatya Institute, Gurgaon, Haryana, India.

Kirti Dutta is Assistant Professor, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan’s Usha and

Lakshmi Mittal Institute of Management, New Delhi, India