Understanding Digital Media Penetration in a Formal Group Setting

The market of digital content (music, publishing, news etc.) has evolved over the past few years, as new players (e.g. internet services, digital service providers, etc.), many of them originally from other sectors, enter the space of the traditional actors. There is an enormous increase in the shelf-presence of digital technologies for content dissipation (e.g. cellular phones, televisions, computer, interactive media, etc.) with provision of features like interactive multimedia, content customization, etc. with media industry becoming increasingly digital and with rapid technological innovations, proper selection of digital media is likely to play a key role in judging a media performance. In this research, we try to identify the factors that can significantly influence the coverage or penetration of a digital media in a formal group setting. In order to carry out the research, we construct a model to explain the penetration of digital media based on well accepted theories related to technology adoption and diffusion. In order to simulate the model, we construct four usage scenarios in order to understand the dynamics associated with the penetration of the digital media within a formal group. Simulation of the model following the four scenarios identifies some of the challenges impacting the diffusion process and some counter measures. The results point to the following sets of pointers to achieving a better success rate in penetration viz. influencing the user demographic characteristics (i.e. interest, intention, etc.), and influencing the system characteristics (i.e. increased usability, etc.). The theoretical and practical implications of our study have also been identified.

Introduction

The market of digital content (music, publishing, news etc.) has evolved over the past few years, as new players (e.g. internet services, digital service providers, etc), many of them originally from other sectors, enter the space of the traditional actors. The consequences of digital technologies for the media industry have been enormous, both for the production and the consumption of digital content. The economics of production and distribution has been radically altered and the context of the economic crisis and related fall in advertising revenues have further accentuated the need of experimenting with new content dissipation models as well as of structural changes. There is an enormous increase in the shelf-presence of digital technologies for content dissipation (e.g. cellular phones, televisions, computer, interactive media, etc.) with provision of features like interactive multimedia, content customization, etc. This poses a challenge both for the organization in charge of the content or information, and for the organization providing or designing the information dissipation services/products. To the former, the challenge is to figure out which digital media to opt for so that the designed content reaches its intended audience in a cost effective manner Proper selection of media is likely to be instrumental in deciding on the proliferation of the dissipated information. To the latter, the challenge is to design and market its product/services in relation to content dissipation in such a manner so as to ensure market dominance and enjoy competitive advantage. With media industry becoming increasingly digital, and with rapid technological innovations, proper selection of digital media is likely to play a key role in judging a media performance. To date, only a couple of inter-disciplinary studies in information systems (IS) and media management (Boczowski, 2005; Pisanias and Willcocks, 1999) have explored how organizations plan their activities in the context of information dissipation using digital technology. The studies were carried out in the context of newspaper organizations only and hence very narrow in scope.

Digital media success is determined by how well the media is able to penetrate within its intended audience (EYGM News Release, 2010). The individuals who are likely to use the digital media also belong to a number of different groups which shape their beliefs and actions. Our research focuses on parameters affecting the coverage or penetration of a digital media in a formal group setting. We define a formal group as one who’s functioning is governed by well-defined policies and procedures (Groups and Formal Organizations, 2010). We base our inquiry on a model that we develop grounded on prominent theories from respective fields linked with the study.

The article is organized as follows. Section 2 reflects upon the background work that informs the research reported in this article. In Section 3, we present the research methodology where-in we discuss the research model of interest. In Section 4, we analyze the model behavior under different constructed scenarios and present the results. Finally Section 5 concludes the article by summarizing the findings and providing directions for future research.

Background

The process of penetration of digital media in a group setting can be seen as an interaction of two interacting processes i.e. the process of acceptance and the process of diffusion. Acceptance involves selection of a technology for use by an individual or a group. In contrast, diffusion involves spread of the technology for general use and application (Carr, 2010). We provide a review of group types, technology acceptance, and technology diffusion below which have been subsequently used in the framing of our research model.

Group Types

A group is composed of individuals who share several characteristics as follows: (1) The individuals are in regular contact with each other, (2) The individuals share ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving, (3) They take one another’s behavior into account, and (4) They have one or more interests or goals in common (Witte and Davis, 2013). Membership of groups is often a mean to reinforce or construct identity. The capacity of groups to reinforce identity, a sense of self and relationships to society, in itself provides an incentive for cooperative behaviour and empowering action in the interests of the group (Alkire and Deneulin, 2002). However, individuals may also co-operate in groups based on a sense of social responsibility, a sense of duty, or commitment, or because they enjoy the activity itself (Sudweeks and Allbritton, 1996). The reasons of existence of the groups have been traced to two prominent theoretical lenses on group development which are recurring-phase theories and sequential stage theories(Robertson, 2005).

Recurring-phase theories (e.g. Bales, 1951; Schutz, 1966) assume a cyclic progression in which phases emerge, recede and re-emerge to discuss issues in greater depth. The theories indicate that certainissues tend to dominate group interaction during various phases but these phases do not follow a consistent order, and rather emerge, recede, and emerge again within agroup (Forsyth, 1983). Among these, Homans (1950) posits that groups develop based on activities, interactions, and sentiments. The strength of a group is therefore a function of the individuals in the group, the interactions of the group members and the influence of the group on the community. Bales (1951) proposed a framework for continuous observation of interactions, called ‘interaction process analysis’. The author indicates that a group proceeds through a series of task-oriented phases (orientation, evaluation and control) in parallel with predictable cycles of socio-emotional behaviour. Schutz’s (1966)Fundamental Interpersonal Relationships Orientation (FIRO) model explains interpersonal behavior in three phases which are cyclical in nature viz. (a) inclusion (this involves defining boundaries, i.e. who’s ‘in’ and who’s ‘out’); (b) control (this involves resolving conflicts of structure and leadership, i.e. who’s ‘top’ and who’s ‘bottom’); and (c) affection (this concerns inter-ember harmony and group cohesiveness, i.e. who’s ‘near’ and who’s ‘far’). Gersick(1988;1989) introduced the punctuated-equilibrium model which suggests that group development is underlined by periods of inertia that are punctuated by periods of change.

Sequential-stage theories propose that groups follow linear phases of group development (Robertson, 2005). Tuckman (1965) proposes four phases of group development viz. forming, storming, norming and performing. The forming phase involves getting acquainted with each other in a new situation, and defining the task descriptions. In the storming phase, conflicts and individual differences come to the surface with solutions being sought for improvement. The hird phase norming finds the group regulating its behavior. Performing, the fourth phase is marked by emphasis on task performance and productivity. The final phase of adjourning which was added later (Tuckman and Jensen, roup’s termination as tasks have been completed. Robbins et al. (1994) proposed a modified model of five phases viz. forming and norming, low performing, storming, high performing, and adjourning, which was found to be robust in an application based on a computer-mediated setup (Romm and Pliskin, 1995). Hare and Naveh (1984) identifies four stages in problem-solving groups viz. latent (where the group agree on factors such as aims, priorities and methodologies), adaptation (involves identifying skills and assigning participant roles), integration (involves flexibility and compromise), and goal attainment.

Groups can be classified in terms of their nature into two broad categories viz. formal and informal (Robbins et al., 1994). Formal groups are generally created by the organization and are intentionally designed to direct members toward some important organizational goal (Moorhead and Griffin, 1998;Zayed and Mostafa, 2005). They can be differentiated on the basis of their membership, task, and nature of technology or position within organization (Mullins, 2010).Formal groups can be classified into command groups, task groups, and functional groups (McMillan, 2015).

Command groups are specified by the organizational chart and often consist of a supervisor and the subordinates that report to that supervisor, for example, academic department chairman and the faculty members in that department (McMillan, 2015). Task groups (also referred to as task forces) consist of people who work together to achieve a common task. Here members are brought together to accomplish a narrow range of goals within a specified time period (McMillan, 2015). Functional groups are created by the organization to accomplish specific goals within an unspecified time frame. Functional groups remain in existence after achievement of current goals and objectives. Examples of functional groups are marketing department, customer service department, accounting department, etc. (McMillan, 2015).

Informal groups are formed naturally or in response to the common interests and shared values of individuals. Informal groups are mostly self created, and consist of employees from different departments, irrespective of their positions with common interest(Burt, 1992; Johnson and Scholes, 2004; Mullins, 2010). Theseare developed out of their daily activities, interactions and sentiments that the workers have for each other (Helliegel and Slocam, 2007). Informal groups are not appointed by an organization, and here the members can invite one another to join from time to time(Greenberg and Baron, 2007). Informal groups can be categorized as interest groups, friendship groups, membership groups, reference groups, primary groups, and secondary groups (Handy, 1993; McMillan, 2015).

Interest groups comprises of individuals having different background and connections but are bound together by some other common interest. Friendship groups are formed by members who enjoy similar social activities, political beliefs, religious values, or other common bonds. Membership groups comprise of those who are part of a big group to which they belong to but they have a minimal relationship, for example, a group belonging to a religious organization. Reference groups are groups that people use to evaluate themselves, for example, the reference group for a new employee of an organization may be a group of employees that work in a different department or even a different organization. Primary groups are characterised by intimate face to face association and cooperation, for example, a family. Finally, secondary groups are those where the interrelationships are more general and remote. The membership of such groups is generally voluntary and can be easily withdrawn.

Technology Acceptance

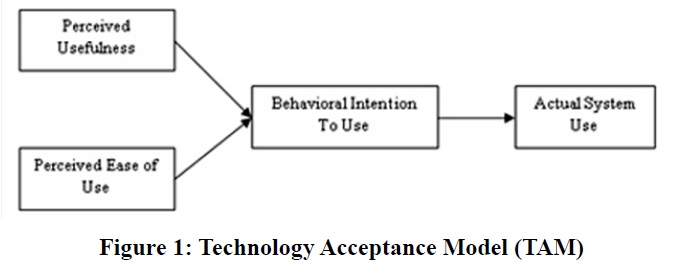

The process of acceptance has been studied in detail based on the technology acceptance model’ (TAM) (Davis, 1989). Technology acceptance model (TAM) is based on the idea that user acceptance plays a critical role behind the success of organizational technological initiatives. Technology acceptance model (TAM) is based on the theory of reasoned action (TRA) (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975) and the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1985, 1991; Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). The theory of reasoned action (TRA)indicates that an individual’s behavior is determined by his or her intention to perform the behavior. The behavioral intention in turn is influenced by two key antecedents: (1) attitudes toward the behavior and (2) an understanding of key referents’ attitudes toward the behavior. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) extends the theory of reasoned action (TRA) to add a key antecedent, perceived behavioral control. Both of these theories serve as the conceptual foundation of the technology acceptance model (TAM) to explain the technology adoption phenomenon. Technology acceptance model (TAM) theorizes that the adoption of a technology by an individual depends upon his/her behavioral intention. The behavioral intention in turn is governed by perceived usefulness (i.e. the extent to which use of the technology is believed to be enhancing the performance (Davis, 1989), and perceived ease of use (i.e. the degree to which use of the technology is considered to be free of effort (Davis, 1989). In the technology acceptance model (TAM), perceived ease of use has both direct and indirect effects. Thedirect effect indicates that perceived ease of use is a catalyst for technological adoption while the indirect effect can be explained as ‘‘stemming from a situation where, other things being equal, the easier a technology is to use, the more useful it can be’’ (Venkatesh and Morris, 2000). Figure 1 presents the block diagram of the technology acceptance model (TAM).

Since the inception, the technology acceptance model (TAM) has been studied extensively in different contexts including in advertising (Huarnget al., 2010), corporate management (Ahuja and Thatcher, 2005), healthcare (Yun and Park, 2010), information management (Behrendet al., 2011), and marketing (Lee and Qualls, 2010). Based on the ensuing contributions, refinement of the technology acceptance model (TAM) into technology acceptance model (version-2) (TAM2) (Venkatesh and Davis, 2000) was carried out. Technology acceptance model (version-2) (TAM2) integrated the determinants of perceived usefulness in its model core which are subjective norm, image, job relevance, output quality, result demonstrability, and perceived ease of use – and two moderators viz., experience and voluntariness. Further refinements led to the foundation of the technology acceptance model (version-3) TAM3 (Venkatesh and Bala, 2008) which extended the previous version by integrating the determinants of perceived ease of use. Technology acceptance model (version-3) (TAM3) theorized that the determinants of perceived usefulness will not influence perceived ease of use and vice versa (Venkatesh and Bala, 2008). All these developments focused on arriving at possible management intervention strategies, and identify possible research opportunities (Chuttur, 2009).

Diffusion Research

Rogers (1983) defines diffusion as “the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system”. The innovation could beany idea, practice, or object that is new to the members of the social system or population (Mahajan and Peterson, 1985), for example, a medicine, an information technology (IT) product, a software development approach etc. An adopter could be any entity such as an individual, a family, a firm, an industry, or a country. In the diffusion process, all members are assumed to be of the same broad type e.g., all individuals or all firms.

A potential adopter transitions through a number of stages such as knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation when encountering and responding to an innovation (Rogers, 1995). According to this stage model, the “decision” stage represents the potential adopter’s decision whether or not to adopt the innovation. Since potential adopters may enter any stage at different points in time and continue in any stage for different lengths of time, the diffusion process extends over a period of time. Based on this transience, adopters are classified as innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards, with a frequency distribution of 2.5%, 13.5%, 34%, 34%, and 16%, respectively (Rogers, 1962, 1995; Brancheau and Wetherbe, 1990), with the cumulative frequency of the distribution resembling an S-shaped curve (Rogers, 1962).

Research on diffusion derives its roots from the diffusion of innovation (DOI) (Rogers, 1983). Diffusion of innovation (DOI) tries to explain how spread of innovation takes place in a society over time through use of various channels. Diffusion of innovation (DOI) has received significant attention in information systems (IS) literature (Ilieet al., 2005; Karahannaet al., 1999; Mustonen-Ollila and Lyytinen, 2003; Ramamurthy and Premkumar, 1995).

Several other models have been proposed to explain diffusion. Critical mass theories propose that a critical mass of potential adopters is instrumental in enhancing diffusion (Markus, 1990). Threshold models indicate that diffusion is dependent on threshold levels of potential adopters in the population (Granovetter, 1978). The “threshold” indicates the proportion of the population who are already adopters. Homophily models argue that diffusion is facilitated by potential adopters occupying similar structural positions (Valente, 1995). In this case, diffusion proceeds as potential adopters model themselves on others in their referent groups. Proximity models contend that diffusion is determined by the proximity of members to others in the population (Rice, 1993) with the proximity defined variously as shared ties, shared positions, or shared spaces, etc. Influence models indicate that two types of communication channels affect potential adopters who are considering an innovation viz. mass media and interpersonal relationships (Rogers, 1995; Nilakanta and Scamell, 1990). Mass media channels like magazines, advertisements, etc. convey generic information about an innovation whereas interpersonal channels share specific and experiential information in shared groups. In mixed influence models, potential adopters are subject to both mass media and interpersonal relationships (Rogers, 1962; Mahajan and Peterson, 1985; Hu et al., 1997).

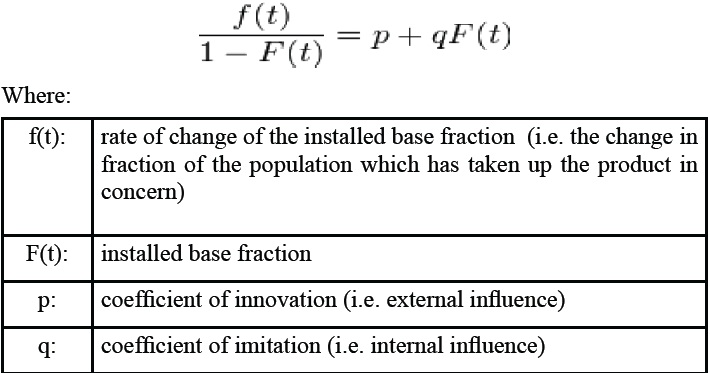

Diffusion of innovation (DOI) has been the basis for research in diffusion modeling by Bass (1969). The Bass diffusion model (Bass, 1969) with foundations rooted on the diffusion of innovation (DOI) explains the phenomena underlying the diffusion of products in a geographic region. Bass (1969) distinguished between two types of buyers: innovators and imitators in his examination of the purchases of a consumer durable over time. “Innovators are not influenced in the timing of their initial purchase by the number of people whohave already bought the product, while imitators are influenced by the number of previous buyers.Imitators “learn” in some sense, from those who have already bought”(Bass, 1969). The intended customers are motivated in using the product based on the marketing and advertising efforts, and also based on interaction with owners and existing customers of the product. The Bass diffusion model can be represented mathematically as follows:

(Bass, 1969; Burt, 1987; Florkowski and Olivas-Lujan, 2006). It indicates the extent to which adopters are influenced by their own intrinsic tendency to innovate and based on factors beyond the population (taking into consideration members of other populations and influences from “mass media” that affects all the populations). In contrast, the imitation coefficient, q, represents the extent to which the adopters emulate other members of the same population. The Bass diffusion model makes a number of assumptions which are as follows (Bass, 1969; Ruiz Conde, 2008):

• The innovation is new for the population in question (i.e., diffusion begins with the cumulative number of adopters

• The characteristics of the innovation or its perceived value do not change over time (i.e., potential adopters would value the innovation similarly regardless of the innovation’s lifecycle or whether they are early or late adopters)

• The innovation, once adopted, is not replaced or discontinued by adopters.

• The size of the population is fixed and is either known or can be estimated

• The potential adopters are assumed to be making their first-time decisions about the innovation

The Bass diffusion model has been widely used in analysis of the diffusion process of various kinds of products in a number of industrial sectors (Hsiao et al., 2009). A series of modifications of the model took place in order to apply the model in different geographies and markets across the globe (Peres et al., 2010). It has been observed that adoption and diffusion within a group are not entirely separate, but the later is likely to be influenced by the former (Peres et al., 2010). The paper presents an attempt to investigate the same in a formal group setting which characterizes an organizational context.

Methodology

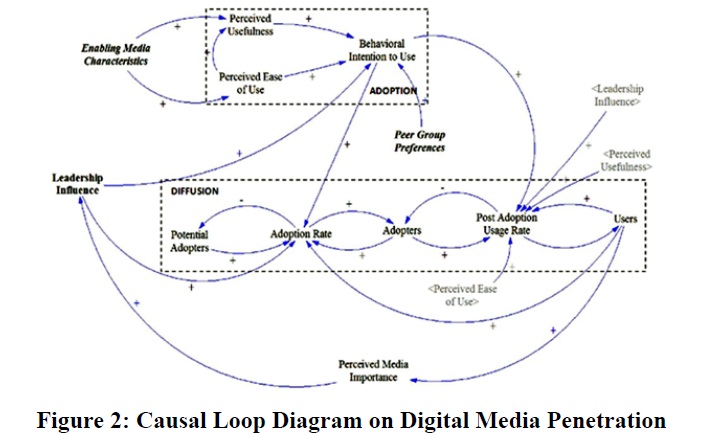

The process of penetration in a formal group setting is contingent on the interaction of various factors related to diffusion over time. These factors again relate to the nature of interactions of the members in the group setting. In the formal group setting, the behavior of the group members are likely to be influenced by the group settings, norms, task characteristics, etc. and have an influence on the way the individuals interact with each other and carry out the intended tasks (Kinicki and Robert, 2003). The nature of interaction is also dynamic and changes over time, which again influences the group dynamics. The system dynamics (Sterman, 2000) is a systemic approach that facilitates investigation of such complex phenomena which evolves over time. SD takes a systemic view of the problem by analyzing the forces that are generated by the structure of the system, and the resultant behavior these forces ultimately lead to. Feedback structures that characterize an SD model represent interaction of parameters representing the problem scenario. Model building commences with the generation of a causal loop diagram (CLD), and is a representation of the hypothesized structure in the form of interacting causal links. Each of the causal links contains a certain polarity. In a reinforcing (balancing) relation, a positive change in the cause results in a positive (negative) change in the effect and it is represented with the help of a positive (negative) link. Delays are represented using a double line intersecting a link. Simulation of the model is achieved by converting the causal loop diagram into a mathematical model consisting of a system of difference equations, and performing initialization of the parameters. The causal loop representation of the digital media penetration model is shown in Figure 2.

In order to understand the model behavior, we have to analyze how the adoption and the diffusion subsectors interact with each other and over time.

Adoption Subsector: This sector resembles the technology acceptance model (TAM). The sector provides explanation on the formation of individual intention towards adoption of a digital media in a formal group setting. Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use drive the formation of Behavioral Intention to Use digital media. Behavioral Intention to Use digital media subsequently dictates the usage of digital media by the individuals. The formation of Perceived Usefulness of the digital media is likely to be based on formal communications within the group based on the perceived value of the intended media. The Behavioral Intention to Use the media by individuals assuming group leadership positions can again be communicated to the group members to re-inforce the group member’s beliefs’ about the intended media.

Diffusion Subsector: The sector parallels the Bass diffusion model. Potential Adopters depict a collection of likely adopters of the digital media after it has been introduced in some way within the group setting. Adopters depict a collection who has adopted the digital media. In the formal group setting, the early adopters can be the individuals assuming leadership positions within the group. Adoption Rate represents how quickly the digital media is being adopted by the members of the formal group setting. Finally Users represent that collection of individuals from among the Adopters who have started using the digital media.

An increase in Perceived Usefulness or Ease of Use within the Adoption sub-sector creates a favourable environment towards initial acceptance of the digital media by selected members belonging to a formal group setting. This contributes to an increase in Behavioral Intention to Use which in turn positively influences the Adoption Rate. The net contribution of this is an increase in Users of the digital media (Diffusion subsector). The increase in the Users pool positively influences group members’ belief’s about Perceived Media Importance (i.e. a measure of perceived value or worth of the digital media in concern). This increased importance of the digital media in turn is expected to heighten Leadership Influence (i.e. the influence that individuals in leadership or equivalent positions in a group have over the group members), that guide individual’s adoption of the digital media. Variations in exogenous variables like Enabling Media Characteristics (a multi-dimensional construct of functionality, equipment performance, interaction, environment, user interface quality, system simplicity, and system quality (Karahannaet al., 1999) representing the characteristics that increase the value of the digital media as perceived by its intended users), Peer Group Preferences (i.e. the choice set of members who are at the same level or status in a formal group setting), etc. are expected to further complicate the scenario.

The model implementation was carried out using the Vensim PLE software. The model parameters (Figure 2) were set in the range of [0…1], with zero depicting the lower limit and one depicting the upper limit (i.e. maximum potential achievable with respect to the concerned parameter).

Results

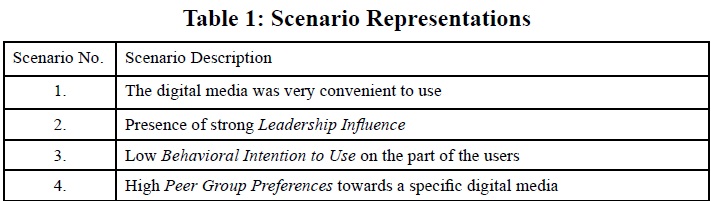

The following four hypothetical scenarios were constructed (Table 1) in order to depict some of the real-life situations governing introduction of a digital media within a formal group setting. We maintain the model exogeneous variables (i.e. Enabling Media Characteristics and Peer Group Preferences) at the nominal level in each of the scenarios.

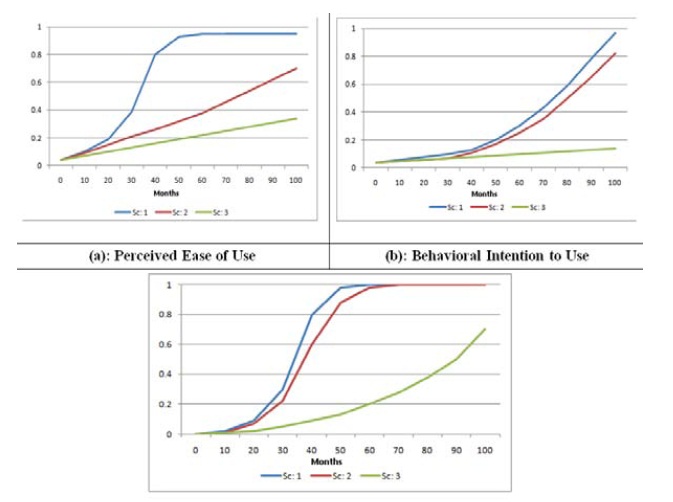

Variation of three key model parameters corresponding to the top three constructed scenarios (Table 1) is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Variation in Key Model Parameters Here

Scenario 1: The digital media was very convenient to use

This replicates the scenario where the introduced digital media has excellent user interface and easy to use features. This is modeled by increasing the value of Enabling Media Characteristics (Figure 2). Figure 3 depicts the impact of the above change on suitable model parameters. As is evident from the figure, the presence of high value of Enabling Media Characteristics leads to an increase of ease-of-use perception among the potential adopters pool and also causes to increase the perception of usefulness (not shown). This influences the formation of behavioral intention towards the digital media thereby accelerating its adoption. All these result in heightened perception of value associated with the digital media, thereby positively influencing the overall dynamics. The findings also explain why a digital media with better usability features has a greater rate of penetration given that the other parameters remain constant.

Scenario-2: Presence of strong Leadership Influence

In this scenario, it is assumed that a member assuming leadership roles exerts profound influence on the beliefs of other members in a formal group setting. In such a scenario, there is tendency to confirm to the preferences of the person assuming such leadership roles (Schminke et al., 2001). Say if such a person has communicated his/her preference towards a specific digital media, the preference set gets also imposed on the other group members, thereby affecting their behavioral intention towards adoption of the same. Side-by-side, this also affects group members’ adoption of the digital media. The pool of users hence depicts an increasing trend over time, and is comparable with Scenario-1 results (Figure 3 (c)). However, with respect to Scenario-1, the variable Perceived Ease of Use is found to settle at a lower value (Figure 3 (a)). This is because the formation of intention here is mostly dictated by the choices and preferences of the group leader. Hence even though a digital media could be perceived to be somewhat inferior, it could become very popular if the reinforcing loop generated through leadership influence assumes dominance in the above manner.

Scenario-3: Low Behavioral Intention to Use on the part of the users

This represents the scenario of users possessing very low intention to use the digital media. The implementation of the same was carried out in the simulation model by multiplying the rate of change of intention with a decimal factor and thereby making it very low. The manifestation of the same can be noticed from the curve of Behavioral Intention to Use with little variation over the duration of simulation (Figure 3 (b)). This fails to trigger the conversion of potential adopters to users which also remains low. The final result is a very low conversion of potential adopters into users, with the pool of Users minimum in this case (Figure 3 (c)).

Scenario-4: High Peer Group Preferences towards a specific digital media

Finally, Scenario 4 look into how peer group behaviors affects an individual’s belief. If the group to which an individual belongs to strongly opines for a specific digital media, this can result in the formation of intention to adopt and use the specific media. Now whether this intention actually translates into the individual purchasing and using the digital media is again driven by other factors like the perceived usefulness of the digital media, the trust of the individual on peer group choices, etc (not shown). However a portion of the potential adopter’s pool gets converted into users of the digital media based on peer group preferences (not shown).

The simulation results illustrate how different scenarios can affect digital media diffusion in a formal group setting. Factors like individual perceptions of ease of use and usefulness regarding a digital media were found to influence the digital media adoption process, but did not guarantee a wider coverage. Leadership roles assumed by individuals were found to have a prominent effect on the extent of digital media penetration. The influence of peer group on the penetration process was also noticeable.

Results also throw some interesting insights. The growth rate of Behavioral Intention to Use could be found to be slowest under Scenario-3. This is because of a lack of desire on the part of individuals to adopt or use a specific digital media. This could be because the digital media has some deficiencies which limit its adoption. Organizations developing such digital media for the purpose of information dissipation can troubleshoot the scenario to find out the exact causes behind such phenomenon. The impact of Leadership Influence on the penetration process (Scenario-2) highlights the role played by influential individuals in shaping others beliefs and actions.

Conclusion

The penetration of a digital media can assume importance when there are competing digital technologies with compatible functionalities, and the organizations producing information doesn’t have a choice but to select a specific media for dissipation of their content. Proper selection of the media can go a long way in deciding whether their information reaches the intended audience or has a greater coverage. This research combines the Technology Acceptance Model and the Bass Diffusion Model in a novel attempt in order to study digital media penetration within a formal group.

Our model tries to represent some of the temporal interactions that happen during the adoption and the diffusion process. Model simulation based on four scenarios highlights some of the challenges impacting the diffusion process and some counter measures. The results point to the following sets of pointers to achieving a better success rate in diffusion viz. influencing the user demographic characteristics (i.e. interest, intention, etc.), and influencing the system characteristics (i.e. increased usability, etc.).

The results have implications for both theory and practice. Theoretically the research has merged to prominent streams of research i.e. the Technology Acceptance and the Innovation Diffusion in order to investigate the penetration of a digital artifact. Since the phenomena under investigation are likely to change over time, the research adopts a longitudinal approach based on simulation and makes a patterns oriented analysis using the scenarios constructed above. From a practitioner’s point of view, the research informs on the levers available to the management to ensure proper penetration of the intended media within the concerned group. As the results indicate, mechanism that can result in positive evaluations of the intended technology to the concerned members, for example, heightened interests, etc. are likely to facilitate better penetration of the intended media. The technology manufacturing organization may also improve the product characteristics like advanced user interface, etc. in order to better market their products to the target audience.

There are some limitations that need to be considered. The model takes into account only a limited set of factors influencing the penetration phenomena. Some later developments in the domains of technology acceptance and diffusion have not been incorporated in our proposed model. There is also a need to re-conceptualize the operationalization of the model constructs. Our study also does not take into account the cost factors, which again could be an ultimate decider on which digital media to opt for, given each individual’s budget and preference sets. The study is just the first step towards taking a holistic view in trying to understand the dynamics of the penetration process, and its inherent uncertainties. Future work is expected to build on this foundation, elaborate on the model structure, and address the limitations as pointed above. Additionally, our findings are relevant with respect to the growing interest of organizations on enterprise social networking software which provides a platform to integrate cloud computing and social applications to provide analytics as per the requirements of the organizations (Enterprise Social Networking, 2015). The penetration of the software can be modeled in order to understand the dynamics that govern its adoption and usage in the organizations under investigation. It remains to be seen how this research informs the future of digital media penetration research the user demographic characteristics (i.e. interest, intention, etc.), and influencing the system characteristics (i.e. increased usability, etc.).

The results have implications for both theory and practice. Theoretically the research has merged to prominent streams of research i.e. the Technology Acceptance and the Innovation Diffusion in order to investigate the penetration of a digital artifact. Since the phenomena under investigation are likely to change over time, the research adopts a longitudinal approach based on simulation and makes a patterns oriented analysis using the scenarios constructed above. From a practitioner’s point of view, the research informs on the levers available to the management to ensure proper penetration of the intended media within the concerned group. As the results indicate, mechanism that can result in positive evaluations of the intended technology to the concerned members, for example, heightened interests, etc. are likely to facilitate better penetration of the intended media. The technology manufacturing organization may also improve the product characteristics like advanced user interface, etc. in order to better market their products to the target audience. There are some limitations that need to be considered. The model takes into account only a limited set of factors influencing the penetration phenomena. Some later developments in the domains of technology acceptance and diffusion have not been incorporated in our proposed model. There is also a need to re-conceptualize the operationalization of the model constructs. Our study also does not take into account the cost factors, which again could be an ultimate decider on which digital media to opt for, given each individual’s budget and preference sets. The study is just the first step towards taking a holistic view in trying to understand the dynamics of the penetration process, and its inherent uncertainties. Future work is expected to build on this foundation, elaborate on the model structure, and address the limitations as pointed above. Additionally, our findings are relevant with respect to the growing interest of organizations on enterprise social networking software which provides a platform to integrate cloud computing and social applications to provide analytics as per the requirements of the organizations (Enterprise Social Networking, 2015). The penetration of the software can be modeled in order to understand the dynamics that govern its adoption and usage in the organizations under investigation. It remains to be seen how this research informs the future of digital media penetration research

References

Ahuja M. and Thatcher J. (2005) Moving beyond Intentions and Toward the Theory of Trying: Effects of Work Environment and Gender on Post-Adoption Information Technology Use. MIS Quarterly 29, 427–459.

Ajzen I. (1985) From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhi &

J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action – Control: From Cognition to Behavior (pp. 11–39). Springer, Heidelberg.

Ajzen I. (1991) The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50, 179–211.

Ajzen I. and Fishbein M. (1980) Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall, NJ.

Alkire S. and Séverine D. (2002) Individual motivation, its nature, determinants, and consequences for within-group behaviour. In. J. Heyer, F. Stewart, R. Thorp (Eds). Group Behaviour and Development: Is the Market Destroying Cooperation (pp. 51-74).Oxford University Press.

Bales R.F. (1951) Interaction Process Analysis: A Method for the Study of Small Groups. Addison-Wesley Press, Inc., Reading, MA.

Bass F.M. (1969) A new product growth for model consumer durables. Management Science 5(5), 215-227.

Behrend T., Wiebe E., London J. and Johnson E. (2011) Cloud Computing Adoption and Usage in Community Colleges. Behavior & Information Technology 30, 231–240.

Boczkowski P.J. (2005) Digitizing the News: Innovation in Online Newspapers. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Brancheau J.C. and Wetherbe J.C. (1990) The Adoption of Spreadsheet Software: Testing Innovation Diffusion Theory in the Context of End-User Computing. Information Systems Research 1(2), 115-143.

Burt RS (1987) Social Contagion and Innovation: Cohesion versus Structural Equivalence, American Journal of Sociology 92, 1287-1335.

Burt R.S. (1992) Structural holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Carr VH Jr. (2010) Technology Adoption and Diffusion. Available at: http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/ innovation/adoptiondiffusion.htm

Chuttur MY (2009) Overview of the technology acceptance model: Origins, developments and future directions. Sprouts: Working Papers on Information Systems 9:37, pp. 1-23.

Davis F.D. (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology.MIS Quarterly 13 (3), 319-340.

Enterprise Social Networking (2015) Retrieved July 28, 2015, fromhttps://en.wikipedia. org/wiki/Enterprise_social_networking

EYGM News Release (2010) Retrieved December 22, 2010, from http://www.ey.com/

US/en/Newsroom/News-releases/Changing-consumer-demands-drive-new-digitalmedia- distribution-channels

Fishbein M and Ajzen I (1975) Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

Florkowski GW and Olivas-Lujan MR (2006) The Diffusion of Human-Resource Information-Technology Innovations in US and non-US firms.Personnel Review 35(6), 684-710.

Forsyth DR (1983) An Introduction to Group Dynamics. Brooks/Cole Pub. Co., Monterey, CA.

Gersick CJK (1988) Time and Transition in Work Teams: Towards a New Model of Group Development.Academy of Management Journal 31(1), 9-41.

GersickCJK (1989) Marking Time: Predictable Transitions in Task Groups. Academy of Management Journal 32(2), 274-309.

Granovetter M (1978) Threshold Models of Collective Behavior. American Journal of Sociology 83(6), 1420-1443. Groups and Formal Organizations (2010) Retrieved August 10, 2010, from http://www.umsl.edu/~keelr/ 010/groups.html

Handy C (1993) Understanding Organizations (Fourth Edition). Penguin, UK.

Hare P and Naveh D (1984) Group Development at the Camp David Summit. Small Group Behavior 15(3), 299-318.

Hellriegel D and Slocum Jr. JW (2007)Fundamentals of Organizational Behavior (First Edition), Thomson South-Western, Mason, United States.

Homans GC (1950)The Human Group. Harcourt, Brace, & World, New York, NY.

Hsiao JP-H, Chyi J and Tzung-Cheng H (2009) Information diffusion and new product consumption: A bass model application to tourism facility management. Journal of Business Research 62 (7), 690-697.

Hu Q, Saunders C and Gebelt M (1997) Research Report: Diffusion of Information Systems Outsourcing: A Reevaluation on Influence Sources.Information Systems Research 8(3), 288-301.

Huarng K, Yu T and Huang J (2010) The Impacts of Instructional Video Advertising On Customer Purchasing Intentions on the Internet.Service Business 4, 27–36.

Ilie V, Van Slyke C, Green G and Lou H (2005) Gender Differences in Perceptions and Use of Communication Technologies: A Diffusion of Innovation Approach. Information Resources Management Journal 18(3), 13-31.

Jerald G and BaronRA (2007) Behavior in Organizations (Ninth Edition).Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, NJ.

Johson G and Scholes K (2004) Exploring Corporate Strategy: Text and Cases(sixth edition). Pearson Education Limited, Harlow.

Karahanna E, Straub DW and Chervany NL (1999) Information technology adoption across time: a cross-sectional comparison of pre-adoption and post-adoption beliefs.

MIS Quarterly 23 (2), 183-213.

Kinicki A and Robert K (2003) Organizational Behavior: Key Concepts, Skills & Best Practices. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, Boston.

Lee J and Qualls W (2010) A Dynamic Process of Buyer–Seller Technology Adoption.

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 25, 220–228.

Markus ML (1990) Toward a “Critical Mass” Theory of Interactive Media. In J Fulk and C

Steinfeld (Eds.) Organizations and Communications Technology (pp. 194-218). Sage, London, UK.

Mahajan V and Peterson R (1985) Models for Innovation Diffusion.Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA.

McMillan A (2015) Group Dynamics.Available at: http://www.referenceforbusiness.com/ management/Gr-Int/Group-Dynamics.html

Moorhead G and Griffin RW (1998)Managing People and Organizations: Organizational Behavior.Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, MA.

Mullins LJ (2010)Management and Organizational Behaviour. Financial Times/Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, NJ.

Mustonen-Ollila E and Lyytinen K (2003) Why Organizations adopt Information System Process Innovations: A Longitudinal Study using Diffusion of Innovation Theory.

Information Systems Journal 13(3), 275-297.

Nilakanta S and Scamell RW (1990) The effect of Information Sources and Communication Channels on the Diffusion of Innovation in a Data base Development Environment.

Management Science 36(1), 24-40.

Peres R, Muller E and Mahajan V (2010) Innovation diffusion and new product growth models: a critical review and research directions. International Journal of Research in Marketing 27 (2), 91–106.

Pisanias N and Willcocks L (1999) Understanding slow Internet adoption: ‘infomediation’ in ship-broking markets. Journal of Information Technology 14 (4), 399 – 413.

Robbins SPT, Waters-Marsh T, Cacioppe R and Millett(1998)Organizational Behavior: Concepts, Controversies and Applications — Australia and New Zealand (second edition). Prentice Hall,Sydney.

Rogers EM (1962) Diffusion of Innovations.The Free Press, New York, NY.

Rogers EM (1983) Diffusion of Innovations. The Free Press, New York.

Rogers EM (1995) Diffusion of Innovations (4th ed.). The Free Press, New York, NY.

Romm CT and Pliskin N (1995) Group Development of a Computer-Mediated Community, Working Paper, University of Wollongong, Wollongong.

Ramamurthy K and Premkumar G (1995) Determinants and Outcomes of Electronic Data

Interchange Diffusion.IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 42(4), 332-351.

Rice RE (1993) Using Network Concepts to Clarify Sources and Mechanisms of Social Influence. In WD Richards Jr. and GA Barnett (Eds.) Progress in Communication

Sciences (Vol. XII, pp. 43-62).Ablex Publishing Corporation, Norwood, NJ.

Robertson EJ (2005)The Effect of Learning Styles on Group Development in an Online Learning Environment. Master Dissertation, Watson School of Education, University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Ruiz Conde ME (2008) Modeling Innovation Diffusion Patterns (Doctoral dissertation). Labyrint Publication, Netherlands.

Schminke M, Wells DL, Peyrefitte JA and Sebora TC (2001) Leadership and ethics in work groups: a longitudinal assessment. Group and Organization Management 27, 272-293.

Schutz W (1966)The Interpersonal Underworld. Science and Behavior Books, Palo Alto, CA.

Sterman JD (2000) Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World. Irwin/McGraw-Hill, New York.

Sudweeks F and Allbritton M (1996) Working Together Apart: Communication and Collaboration in a Networked Group. In CD Keen, C Urquhart and J Lamp (Eds),

Proceedings of the 7th Australasian Conference of Information Systems (ACIS96), Department of Computer Science, University of Tasmania, pp. 701-712.

Tuckman B (1965) Developmental Sequence in Small Groups. Psychological Bulletin 63(6), 384 – 399.

Tuckman BW and Jensen MC (1977) Stages of Small Group Development Revisited.

Group and Organization Studies 2 (4), 419-426.

Valente TW (1995) Network Models of the Diffusion of Innovations. Creskill, Hampton Press, NJ.

Venkatesh V and Bala H (2008) Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decision Sciences 39 (2), 273-315.

Venkatesh V and Davis FD (2000) A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies. Management Science 46 (2), 186-204.

Venkatesh V and Morris M (2000) Why don’t Men ever Stop to Ask for Directions? Gender, Social Influence, and their Role in Technology Acceptance and User Behavior.MIS Quarterly 24, 115–139.

Witte EH and DavisJH (2013)Understanding Group Behavior: Volume 1: Consensual Action By Small Groups; Volume 2: Small Group Processes and Interpersonal Relations. Psychology Press.

Yun E and Park H (2010) Consumers’ Disease Information-Seeking Behavior on the Internet in Korea.Journal of Clinical Nursing 19, 2860–2868.

Zayed AM and Kamel MM (2005) Teams and Workgroups. Pathways to Higher Education, Cairo.

Rahul Thakurta is Faculty of Information Systems at Xavier Institute of Management Bhubaneswar, Bhubaneswar, India. Email: rahul@ximb.ac.in.