MULTIPLE RELATIONSHIPS WITH MULTIPLE STAKEHOLDERS: THE SCOPE OF RELATIONSHIP MARKETING FOR PUBLIC SERVICES

Following Gillett’s (2015) study showing the positive link between relationship marketing (RM) and performance in local government, this paper advances understanding regarding the scope of relationships. Multiple case design was used involving key informant interviews, together with internal and externally published documents from four local authorities. Findings showed that the scope and scale of activities of local councils involves the public at large, with varying and changing needs. Output such as financial efficiency as well as broader outcomes for the community must be demonstrated. From these findings the author has conceptualised a set of key relationships that managers should pay particular attention to when procuring goods and services. The proposed framework, used in conjunction with the seminal stakeholder planning process suggested by Bryson (2004), will enable decision-makers to visualise clearly the broad scope of procurement, and how the relationships between local authorities and suppliers are part of a wider and interlocking network of relationships. Findings should also be of interest to policy makers concerned with improving the long-term effectiveness and efficiency of public sector procurement.

INTRODUCTION

Responding to the quantitative study of Gillett (2015) which demonstrated a positive statistical relationship between perceptions of relationship marketing (RM) and organizational performance in the context of local government procurement; this paper provides rich qualitative insight to advance understanding about the scope of relationships important to procurement.

Procurement an essential aspect of local authorities and particularly worthy of investigation because it relates to most, if not all, of the other council functions as well as broader stakeholders, as this paper demonstrates. The main contribution of this paper is a framework for use by planners and managers when conceptualising the different types of relationship that influence, or are influenced by, the councils approaches to procurement. Drawing upon data gathered from experienced procurement officers, the framework will be particularly useful in instances where procurement has been devolved to managers and junior employees outside of the purchasing or procurement function, who might be less experienced at planning procurements, and may have a relatively narrow understanding

of the subject. The framework, used in conjunction with the seminal stakeholder planning process suggested by Bryson (2004), will enable them to visualise clearly the broad scope of procurement, and how the relationships between councils and suppliers are part of a wider and interlocking network of relationships. Findings should also be of interest to policy makers concerned with improving the long-term effectiveness and efficiency of the local government’s procurement policies.

The geographic context of this paper is England in the United Kingdom, where the range of local government spending varies from routine items of relatively low financial value, such as stationery, furniture, printed

forms, or even temporary office staff; to highly complex policy solutions, such as construction, private finance initiative projects, or support to major change initiatives. As such, the government is often the largest buyer of

goods and services within an economy Jostet et al (2005). Importantly, the laws and guidelines around public procurement in England are driven by those set at the European level for the public sector in general (OGC, 2008) meaning that in many ways the English case is not very dissimilar to its European neighbours. Furthermore, the ‘content of the policies being pursued in the UK have much in common with experiences observed elsewhere (notably New Zealand, Australia and the USA), and provide a valuable test bed for reforms that may be deployed in other countries in the future Martin (2002) As such, the findings and conclusions of this study should have applicability in wider geographic contexts.

For example, local authorities around the world have faced increased public expectations and demand for many of the services they provide, and have been encouraged to re-think their approaches to commissioning and procurement Healey and Milton (2008). To reduce costs, local councils have been advised to enter into relationships known as collaborations with other authorities Agranoff et al. (2003); OGC (2008); NAO and Audit Commission, (2010). At the same time they have also been encouraged to commission services to private suppliers, and to develop links with SMEs, social enterprises, and local economies as part of a plural economy to achieve a wider social value. In some cases public-private joint ventures (PPJV) have been created as new institutional entities that are governed in alliance with private sector partners Andrews et al., (2015).

Public management literature has suggested the usefulness of service marketing and relationship marketing. Studies by Osborne (2010); Osborne et al.(2013; 2014), and Gillett’s (2015) show its applicability for local government procurement, supporting the call from national governments for local authorities to collaborate and to use procurement at the heart of strategic approaches, for achieving efficiency and effectiveness.

For example, the United Sates of America’s Council for Community United We Serve (2013) and the United Kingdom’s Small State big society agenda The Conservative Party(2010); which have emphasised social

value as a criteria in public sector commissioning and tendering Doherty(2012) argues that in order for service marketing and management academics to influence the future of RM theory in the public sector context, it is

imperative that they join the debate; and do not leave it to the public management journals to lead on an area that is so fundamental to the services marketing discipline.

The findings of this paper will be helpful to local government officers in two ways: Firstly, the author draws together previously fragmented bodies of literature to explain more clearly the convergence within RM literature, and the usefulness of RM and service -marketing theory for local government procurement. Secondly, the author proposes a new model to define the scope of RM specifically for local government procurement, and identify a series of key relationships within this scope that should be considered by local government officers. It is envisaged that the findings will encourage adoption of a relational approach, and be used to underpin planning and behaviour in procurement, typified by longer time scales and higher degrees of complexity and value, through partnerships and collaborations.

Theoretical Framework

Academic research has shown that approaches to the procurement and commissioning of public services can range from transactional to relational (Bovaird, 2006); and it should be noted how ‘people and relationships are of critical importance’ (Williams et al., 2012, 83). Bovaird (2006) describes a change in public and private sectors from a transactional model whereby, principals procured adversarially from agents, towards new approaches where the ‘emphasis has switched dramatically to collaborative behaviour whereby each party expects to reap benefits from helping to make the joint working more successful’.

These academic assertions are evidenced within literature published by the UK Government, that shows that there has been a greater emphasis since 2003 on commissioning services to private suppliers, collaboration with other public sector authorities, and increasing emphasis on building links with small and medium sized enterprises, social enterprises, and local economies; as part of a plural economy to achieve social value.

Bovaird (2006) explains this shift as, deriving from a number of theoretical sources such as transaction cost minimization in economics, economies of scope in collaborative networks, strategic alliances and collaborative

advantage in strategic management, and relationship marketing (RM). RM appears to be particularly interesting because public procurement has given a new impulse to the use of market management, marketing approaches

and techniques. Marketing is now much more often seen as an approach to multi-stakeholder co-planning, co-design and co-management of public services. In other words, relationship marketing is seen as a set of collaborative relationships linking stakeholders in the pursuit of their mutual interests’ (Bovaird 2006, Pg.84).

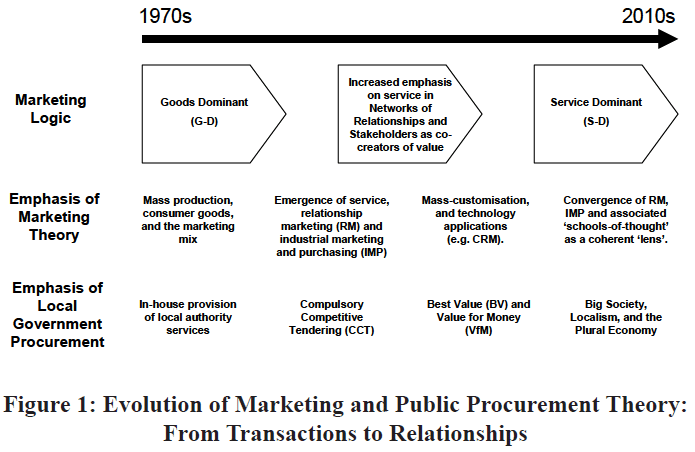

The shift in emphasis from transactions to relationships is shown in Figure 1, which showcase ideas about marketing and public procurement have evolved in tandem.

Despite the general move towards a relational approach to procurement, RM theorist Evert Gummesson is still critical of the way in which many public bodies have often behaved in practise, and identifies the non-commercial

relationship (Gummesson 2002; 2008a) to explain the way that consumers interact with public authorities such as local governments.

Gummesson (2008a) believes public authorities have fundamental properties, that separate them from the commercial sector and characterise their relationships because of disinterest, inertia, and red tapism. He believes

the values and management within government organisations to be based on a ‘bureaucratic-legal paradigm’ rather than on a relationship and service paradigm, and observes a misalignment between legal and bureaucratic values, which prioritises rule and ritual over actual issues and outcomes; and what citizens perceive as fair, as well as problems associated with power asymmetry. Similarly, Vargo and Lusch (2004) address the effects upon service and customer relationships caused by large organisational size and micro specialised functions. Their work has emphasised the importance of a service dominant logic rather than a good dominant logic for marketing, and is of relevance to the local government, which has been identified as being bureaucratic in structure Andrews et al.(2005);

Vargo and Lusch, (2004; 2008; 2011). Vargo and Lusch (2004) believe that in such organisations, workers perform micro specialised tasks and pass the work on to another worker or department who then performs another activity, and so on, resulting in a long chain of activity where no workers pay one another and the majority have no direct contact with customers.

In this situation workers land up ignoring quality and customers. RM theory suggests that the ability to build and sustain networks with internal and external parties has become crucial; as it is fundamental for developing core capabilities, sustaining strategic intent, and building the value generating processes of organisations, as explained by Hunt and

Morgan (1994); Kotler (1994); Grönroos (2000a). RM suggests relationships are at the core of human behaviour society being a network of relationships, marketing and business as subsets or properties of society

Gummesson (2008a).

Clarkson et al. (1997) updated by Gillett (2015) analysed the various models published up until that point, which attempted to conceptualise the scope of RM. Their detailed analyses of contrast and convergence between different customers, partners, stakeholder groups or markets identified within literature appear to be the most comprehensive attempts at synthesising a general framework for the scope of RM. Furthermore they identify four stakeholder groups or markets with whom organisations have relationships: customer, supplier, external stakeholders and internal stakeholders.

The applicability of RM and the service dominant logic for the public sector has become a topic of debate, although conceptualisation is still tentative. A stakeholder based perspective is supported by Bryson (2004) who identifies that, ‘key stakeholders must be satisfied, at least minimally, or public policies, organisations, communities or even countries and civilisations will fail.’ Meanwhile, Godson (2009) writes of his experiences teaching RM to practising managers on Postgraduate Masters programmes.

He found that those working in local authorities ‘admitted that this was the first time that a marketing subject had had much relevance for them’ (Godson, 2009). McLaughlin et al. (2009) echoed this view, suggesting that relationships between public sector organisations and their partners can benefit in situations, where relationships are characterised by high trust and a high interaction. Osborne (2010) identified however that in practice, the implications of differences between manufacturing and service processes for public management and marketing are not generally recognised. He proclaimed that services management theory could provide a basis for improving understanding and delivery of public services, which have traditionally been based upon the theory developed for manufacturing industries such as the ‘lean’ production theory, and suggested RM in particular as being useful for developing public management theories related to marketing services to end users.

RM and SDL theories are applicable to public management because the idea of a broader value is consistent with the responsibility of councils to meet the needs of society, by looking beyond the profit motive often associated with transactional marketing and private firms. In RM and SDL, the focus is on win-win or mutually beneficial outcomes. SDL has conceptualized value as value in context; where context is defined as a set of unique actors with unique reciprocal links among them Chandler &Vargo, (2011) and can help encourage consensus of thinking to address problems associated with micro specialisation; often associated with large bureaucratic organisations Vargo and Lusch (2004). In contrast to transactional or less holistic perspectives of marketing, in RM and SD L the role of the

buyer is also seen as being equivalent to and on par with that of the seller Grönroos (2011); meaning that it is more useful than older theories of marketing in the context of investigating buyer supplier relationships.

Perhaps the greatest argument for the role of RM in public management is provided by Gummesson (2008a) who identifies, that in society both consumers and businesses require a basic level of security trust, reliability, predictability, reduction of uncertainty and risk. Therefore, moral and ethical promises to perform services, deliver goods, or engage in some form of collaboration are core concept critical in all relationships.

‘A corrupt and unpredictable government sector makes it difficult to compete with more reliable societies…relationships can create security… and open up for a plus some game, for win-win…it is the soul of RM.’

Gummesson (2008).

The Objective of this Study

Specifically, the aim of this paper is to develop a framework that defines the scope of relationships that can be employed for local government procurement, and can be used strategically by council buyers and others to

conceptualise their procurement network. The objective is also to identify the most significant relationships as ‘Key Relationships’. The study shall also identify implications and practical considerations associated with these key relationships, to guide council officers in their procurement planning, and which should also be of interest to policy makers concerned with improving the long-term effectiveness and efficiency of local government procurement.

Methodology

Case study research was undertaken using multiple methods of data collection. Multiple case designs were used, for the purpose of exploration and theory building Yin(2003). The literature is not conclusive in its recommendation

for any ideal number of cases Eisenhardt (1989); Perry, (1998); Yin (2003); Gummesson (2008b) although four cases is cited as sufficient Eisenhardt as mentioned by (1989) and Hedges (1985). As cases were undertaken for analytical rather than statistical generalisation, a vast sample was not necessary. According to Yin (2003), each case should only be undertaken if it serves a specific purpose within the overall scope of the enquiry; for example, on the basis of similarity or difference between cases.

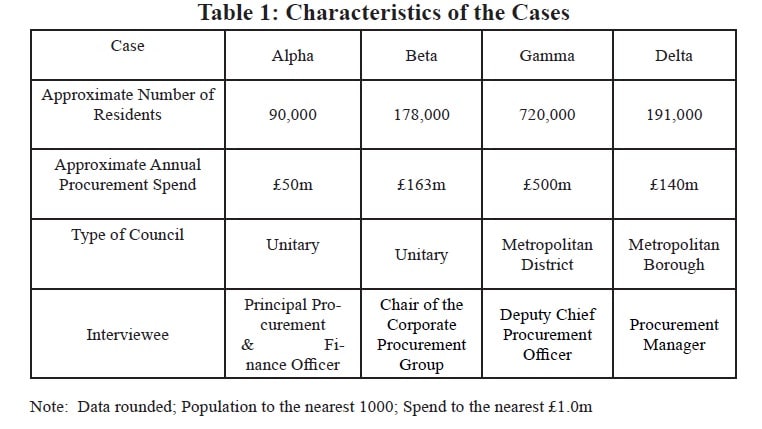

Four local authorities were included in this study, which involved key informant interviews, together with internal and externally published documents such as procurement information made available to existing and prospective suppliers. Characteristics of the case councils are summarised for the purpose of comparison in Table 1, including information about the variation in size and expenditure between the cases. From the available information, it was possible to see that the cases comprised a diverse sample of varying sizes (one small, one very large and two intermediate organisations). The sample covered a broad scope of geography (such as towns, cities and rural areas) and with central procurement functions of differing sizes or establishment. Although all of the case study councils

were located in the North of England, these were not all neighbouring councils.

Data Collection

For this study the units of analysis Trochim (2006) was the buyer-supplier relationship between each local council, and the organisations which supply goods and services. The scope of the unit of analysis included decision-making, activities, behaviour of the individuals and organisations en masse involved with these relationships and the effect upon such relationships within a wider network of stakeholders. Research typically focussed on parties within the buying organisations (the councils) with responsibility for relationships, although much of the data was provided by managers from procurement departments, who were not often involved in day today contact with suppliers.

The study involved conducting semi-structured interviews with council representatives offering a strategic and corporate level perspective of procurement. A set of questions was emailed to each participant at least one week prior to the interview taking place, with the purpose of assisting the interviewees to prepare for the interview Khan and Schroder (2009). An audio recording was made of each interview using an MP3 recorder. Additional to the key informant interview, documentary data was gathered including brochures and strategy documents, website content and externally published sources.

Findings and Discussions

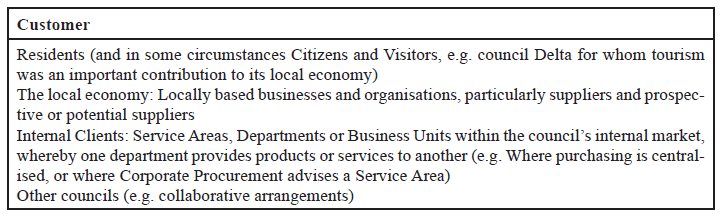

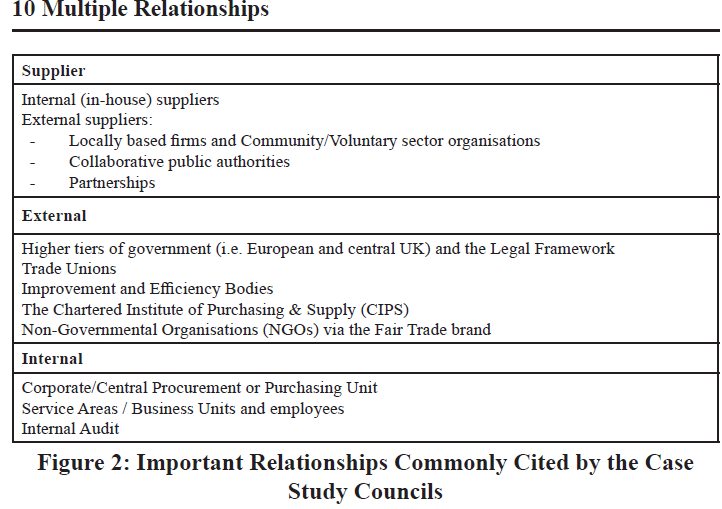

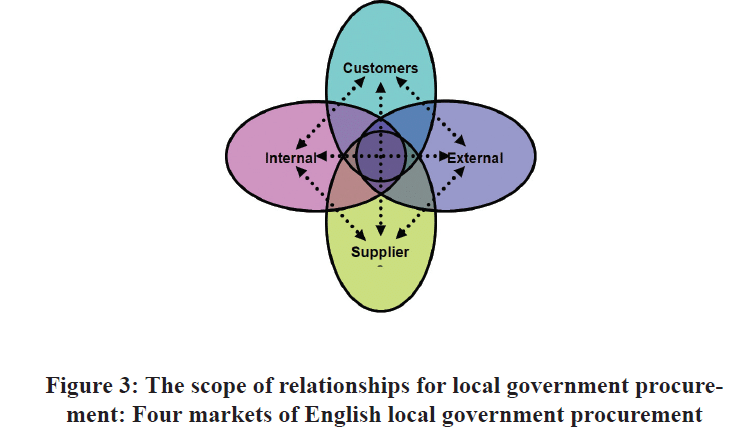

Findings showed that the scope and scale of activities of local councils involve multiple stakeholders with varying and changing needs. Outputs such as financial efficiency as well as broader outcomes for the community needs to be demonstrated. There was convergence between the councils regarding stakeholders with whom relationships existed. Those that were commonly cited by the case councils as being important are summarised in Figure 2 and categorised into four broad of non-mutually exclusive stakeholder categories which can influence, or be influenced by procurement behaviour. These categories were found to be consistent with those identified within the literature review as customers, suppliers, external stakeholders and internal stakeholders.

Figure 2: Important Relationships Commonly Cited by the Case Study Councils

These findings can be synthesised to visualise the scope of relationships in the conceptual model depicted by Figure 3. The area of overlap shows clearly how stakeholders can have multiple types of relationship with councils, and therefore exist within multiple markets simultaneously. The arrows depict the flow interaction (and interdependence) between markets.

Figure 3 expands the view of procurement from customers and suppliers to an inter-woven network of stakeholder relationships. This framework can be used to aid understanding and analysis. For example, to help councils

identify which relationships need to be considered when planning procurements. Findings relating to each of the four market categories are now presented, after which the author identify a series of ‘Key Relationships’ which exist within and between the markets.

Customers

It was observed that residents were mentioned in all cases, as was the local economy, particularly local businesses. From the perspective of the Central Procurement Departments, also included in the customer markets were the Service Areas and Departments or ‘business units’ within the councils, who used their services or supplied to them, as well as to each other. An example of the types of departments served by corporate procurement was provided by the interviewee of Beta who mentioned; that his department had a Service Level Agreement with the Legal Services Department of his council, and also with the in-house construction providers. Similarly, the interviewee of Gamma mentioned that his procurement unit had their own legal team who provided guidance to buying officers in other service areas.

Also mentioned were collaborative buyer supplier arrangements, where councils become customers of other councils. For example, Gamma had started the development of a peer support network where they would deliver a help desk to answer calls from other councils regarding supplier contract management; and additionally manage approved supplier lists for other councils. Such as for councils that were relatively less resourced: ‘The smaller districts like (Alpha) have only got two or three people in procurement, they can’t necessarily cope with the demands coming from their clients, and that’s where we could move in and provide that procurement service to them.’

(Interviewee, Gamma)

Another example was Beta, which according to the interviewee of Alpha, operated a waste disposal plant that served all of the other councils in its sub-region, and purchased rock-salt for use on roads by itself and its neighbouring councils. Similarly, interviewees of Alpha, Gamma and Delta identified their organisations as being customers of their neighbouring councils. Collaborations between councils are therefore also discussed within the analysis of supplier relationships.

Suppliers

Overall, the findings indicated that the case councils procured a broad range of goods and services of variable complexity, cost and duration, from one-off purchases to longitudinal agreements. In the case of Beta, because of the broad scope of supply, relationships with its ‘supplier market’ also varied. The diversity of its business required that different types of relationship must exist in order to be appropriate:

‘The purpose of having different types of relationships is because we’ve got this wide diversity of business, we’ve got to have different relationships in order to be appropriate. It’s nonsense to take the [construction partner] relationship and use that to do motor cycle training. The basic principles of that [construction partner] relationship, fine, but the intensity of it and the effort that goes into it, not fine. You’re talking about a business that’s probably worth over £300,000 a year to [construction partner] versus one that’s £30,000 a year.’ In Alpha, because of the importance placed on the relationship between case councils and their residents and local economies, there had

historically been a tendency for buying officers to want to procure from a limited range of local suppliers in order to achieve ‘community benefit’.

Often this was legacy behaviour based on historic relationships: ‘Around here there is a lot of local input, especially from councillors, to try and keep things local…it is this perceived ‘community benefit’ that’s always operated in a small town like Alpha.’

(Interviewee, Alpha)

The preference for local supply was also evident in Beta, Gamma, and Delta. To illustrate, Beta’s sustainable commissioning and procurement strategy document stated, that in order to improve ‘the procurement and

commissioning cycle’ it would ‘advertise tenders that stimulates the local supply base while meeting EU regulations’. The interviewee mentioned that these regulations should be interpreted and followed so as to benefit residents:

‘We must look to how we can follow them to the advantage of our local communities as best as we can. One of our fundamental tasks as a council is to improve the quality of life for our residents. And if that involves keeping as much money within the community as we can, then that’s a proper thing to do, right thing to do.’

(Interviewee, Beta)

The procurement sections of the case authorities’ websites demonstrated that Alpha and Gamma had signed up to the Small Business Friendly Concordat, a commitment from the Local Government to encourage competition and foster innovation, particularly from Small and Medium sized Enterprises [SME’s], which themselves could include local businesses, social enterprises and Voluntary and Community Organisations. Similarly, Delta’s Sustainable Procurement Strategy document reported, that it had signed up to a compact with its local community and voluntary sector, to enhance their relationship and encourage organisations from the sector to supply to the council.

Although the idea of local supply was considered positive and actively encouraged by all four cases so long as it was within the law, the interviewee of Alpha had previously been frustrated at the preference of buying officers to procure from an established and limited repertoire of firms, which he perceived to be based solely on their locality or size, or familiarity with the buyers. He reported that this had caused a degree of friction with the procurement department, who tried to uphold the council’s objective of being non-discriminatory, and to welcome bids from new

as well as established suppliers, regardless of geographic location and size of organisation; although this had been difficult (interviewee, Alpha).

Another type of supplier relationship which emerged significant was collaboration between councils. Two forms of collaboration were referred to:

i) Firstly joint procurements, whereby councils purchased collectively from suppliers, and were evidenced by interviewees in all cases. The common method was to establish framework agreements between multiple councils

and a supplier for a pre-determined range of goods, which councils could then purchase, as they would from a catalogue; but with increased buyer power due to the economies of scale achieved by the collaboration.

The interviewees of both Gamma and Delta believed, that in addition to improving time and cost efficiencies, framework agreements enabled their council to develop relationships with suppliers as they learned about each

other’s needs.

ii) The second type of collaboration identified was that of one council providing a service to, and on behalf of, other councils. For example, the interviewee of Alpha reported that one council in the sub-region administered certain back-office services such as pension management, on behalf of its neighbours. Again, there was a noticeable commonality, that such collaboration tends to be with neighbouring authorities. One explanation was that this can sometimes be because legacy relationships existed with other councils within a region or sub-region, particularly where larger councils had fragmented into smaller unitary authorities (interviewee, Gamma).

There was some ambiguity regarding the use of the term ‘partnership’, as interviewees from Gamma and Delta both used the term in relation to co-operative purchasing, such as, collaborative framework agreements, as well as to the sort of partnership arrangements referred to by construction and building services. This was due to frameworks sometimes being used within partnership arrangements. ‘Framework contracts to me are not always partnerships, but we’d use a framework contract for a partnership as well’ mentioned an interviewee at Gamma, although it is important to draw a distinction.

Interview data in all cases clarified the nature of true partnerships, citing mutual or ‘win-win’ benefits, common goals, relational rather than adversarial behaviour, and understanding of organisational culture as important

characteristics.

External Market

It was found that local government relationships with external organisations could be complex in nature, and tensions occurred between networks of various external relationships. Practical difficulties stemmed from issues

of governance and from conflicting agendas amongst the upper echelons of the government, because the wants of departments differed. Higher tiers, for example, the European and UK Government and associated legal systems aimed to uphold the importance of public interest and requirement for councils to demonstrate probity, accountability, transparency, and the achievement of the best value for money. The significance was most effectively articulated in the Sustainable Commissioning and Procurement Strategy of Beta, which stated ‘Remaining within the

complex EU rules and regulations is at the heart of effective procurement’.

The interviewee of Alpha perceived that higher tiers of government, specifically the UK central government, had a great deal of influence on procurement relationships:

‘It’s not about who is in control between the two organisations, it’s who can handle it better, because neither are in control in the public sector. It’s the rules and regulations and policy makers in Whitehall who are

really the ones in charge.’

(interviewee, Alpha)

Procurement rules imposed and upheld by the legal system and higher tiers of government dictate that, with the exception of low value one-off purchases; contracts are required for procurements. Furthermore, councils must demonstrate the criteria upon which they based their choice of supplier, and also what the maximum duration of the contracts should be. Interviewees from Beta and Delta indicated, that these limitations can be a cause of frustration for councils and for their existing or prospective suppliers, and can damage relationships. To illustrate the interviewee of Beta talked about the limitations of choice of supplier and stated that ‘we’ve got a scoring system, we must follow it…we’re hamstrung by that’. In relation to existing suppliers, Delta reported how the contract lengths stipulated by European law, and the need to re-tender, had caused a relationship to break down when a construction partnership was re-tendered towards the end of the contracted period: ‘Inevitably that only runs for the period it is allowed to run…under

European law, so we re-tendered that at the end of last year, and we had to go for three new partners. One of the partners continued as an existing partner, they were successful, and we brought in two new partners, and one of the partners lost out. They were very, very unhappy about that and there has been a real breakdown of the relationship and there’s had to be arbitration over monies owed and they spat their dummy out really on that, so they can break down in that situation and that was unfortunate. I think they thought they were going to be assured of that partnership continuing, but they didn’t come out of the tender exercise as well as other companies.’

(interviewee, Delta)

To ensure that the requirements and constraints required by the external market were being met, all four case councils had produced procurement strategies underpinned by the National Procurement Strategy, procurement law and other obligations stemming from the European and Central government, such as environmentally sustainable procurement and community benefits. In the case of Alpha, further complication occurred when the needs or expectations of different government departments were conflicting or contradictory with one another, and with the

system of rules and governance. The interviewee perceived his council’s powers to be limited because of the upper tiers of government:

‘It’s quite difficult when you’ve got that push from one government department, another department saying ‘do local and as small as possible’ (i.e. the small business part of the treasury) and also the section for social enterprise and the voluntary sector in the cabinet office who are now pushing we should now give as much work as possible to the voluntary sector. So we’re caught in all that and all I can say is look we’ll try but the rules

are against it.’

(interviewee, Alpha)

‘Ask them to build capacity within the voluntary sector and they say that’s another department’s problem. I can encourage buyers as much as I want but if they can’t get out there and build the capacity of the voluntary sector or small businesses then they’re flogging a dead horse. Government, whether national or local, isn’t joined up at all from that point of view. There are far too many barriers.’

(interviewee, Alpha)

Similarly, Alpha found that encouragement by upper-tiers of government to use electronic procurement methods, such as e-Auctions in order to achieve cost efficiencies was detrimental to the other objectives required of councils in achieving economic development and community benefit. Rather than purchasing from a range of smaller firms, a single large supplier could win contracts at a short-term loss. The Interviewee provided an example where local stationery suppliers had lost out in a recent ‘reverse auction’ won by a major national supplier whose strategy was to target councils with a very low offer:

‘All we can do is encourage our small local suppliers to encourage (major supplier) to become a sub-contractor. So we’ve defeated our economic development and community benefit aspect by going along with one of the lines government has given us.’

(Interviewee, Alpha)

Beta and Delta demonstrated that it was possible to address the problem of building-in community benefit to a certain extent by including criteria relating to local employment and training within procurements. To illustrate, findings from Beta suggested that the inclusion of targeted training and recruitment requirements within contracts and tenders had so far been successful, as five local residents employed as part of a construction project were still employed beyond that contract (Interviewee, Beta).

Delta had a similar targeted recruitment and training approach: ‘They don’t actually have to be from the borough of (Delta) but inevitably if the construction is taking place in (Delta) they will be from the region. So we can do that and that’s obviously got community benefits.’

(Interviewee, Delta)

Another influence regarding councils’ procurement relationships was their relationship with trade unions. In particular, unions appeared to be especially concerned with councils’ commissioning services to external providers and the impact upon employment for the council’s existing workforces. This issue was supported by the legal framework; namely the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations (TUPE). The Interviewee of Gamma reported that TUPE issues were included in its ‘protocol on outsourcing’. Further evidence to suggest the

importance of unions was a report by UNISON which critiqued Delta’s strategic review of services and potential extensive outsourcing of its Service Areas.

Internal Market

A point of convergence between all four of the case councils was that although corporate level procurement departments existed, much of the procurement activity was actually devolved. The interviewee of Alpha stated

that his procurement unit ‘bought very little’. Departments were supposedly empowered to undertake their own procurements with information and guidance provided by the Procurement Department:

‘Each department and section could deal with managing their supplier relationships. But I’m about making introductions and one of the things I have on the back burner is to put together some guidance on simple supply

management – how to talk to people, how to build relationships with suppliers.’

(Interviewee, Alpha)

Similarly to Beta, it was found that a consultative advisory relationship, as well as an authoritative relationship existed between the procurement unit of Alpha and its Service Areas, to which much procurement was devolved. In this case the consultative advisory relationship involved guidance on how to build supplier relationships and the authoritative relationship involved encouragement or cajoling to follow procurement rules and guidelines, such as challenging historic procurement sources and methods.

In Beta, procurement was devolved to its four Service Area Directorates with the objective of allowing commissioning and procurement to be undertaken by officers, knowledgeable in specialist areas inherent in each

Service Area or Department. Service Areas had at times also bought from and supplied to one another whilst the purpose of the Corporate Procurement Department had been to monitor, control, offer guidance to buyers, and undertake strategic or council-wide procurements (interviewee, Beta).

Much procurement was also devolved in Gamma and because of its size, some of its departments had their own specific procurement teams. The contrast with Alpha’s procurement resources demonstrated the differences that exist between councils and indicated the difficulties in trying to generalise or prescribe procurement policy across the entire sector.

A similarity was that an authoritative as well as a consultative advisory relationship between the Corporate Procurement Unit and Service Areas also existed in Gamma. Because they have their own legal experts, the

Corporate Procurement Unit ‘advise people what to do and what not to do, where to get the advice from, and so on’(interviewee, Gamma). It was also the Corporate Procurement Unit which decided upon the suppliers, from whom the Service Areas were allowed to purchase although it should be noted; that the criteria regarding which prospective suppliers were chosen were developed in consultation with the Service Areas.

In Delta, devolvement involved Service Areas being able to decide ‘how their procurement activity takes place and when it takes place…at the end of the day it’s down to them to do it’ albeit with ‘advice and support’ from the Unit (interviewee, Delta). Therefore, the role of the Strategic Procurement Unit could be described as consultative and advisory one.

The relationship could also be authoritative as evidenced by the Strategic Procurement Unit’s responsibility for procurement strategy, council-wide purchasing, contract management and spend analysis. An example of the

way in which this relationship operated was, the method used to monitor how the Service Areas adhered to procurement laws regarding contract duration, and the requirement to re-tender rather than automatically re-buy

from existing suppliers.

Although it is possible to see that devolved procurement could improve flexibility and be suitable where needs are specific, in Beta it was acknowledged that devolvement of procurement had led to some purchases being made by employees who were not skilled at the task; for example, junior or inexperienced staff. In Alpha, such devolvement had led to difficulty and inefficiency where delegation to lower tiers of the organisational hierarchy occurred, without sufficient supervision or training, in which case the decision would sometimes get passed back up to the higher tiers:

‘Junior positions with budgets of, say £10,000 will stick rigidly to what they’ve always done…you’re supposed to empower your workforce to be able to make decisions, but they just pass it up for someone to tick the box. So you don’t get the mix, especially if it goes up to somewhere like ‘member’ level of ‘chief officer’ level who then makes the final decision whether it’s £20,000 or £10million, that’s the irony.’ (Interviewee, Alpha).

Alpha showed how it could also be problematic in instances where basic products used throughout the council were being procured separately. The interviewee identified that silos had occurred between departments because of a ‘budget-led’ culture. A fragmented approach to stationery purchasing had occurred where departments were all purchasing separately from the same supplier, without considering what other departments were doing and the cumulative amount of money involved. Alpha’s solution was to re-centralise areas of purchasing where it had identified departments were buying the same items. It was believed by the council that this re-centralisation would enable them to benefit from the economies of scale gained from bulk orders, and reduce the problem of poor record keeping (interviewee, Alpha).

On a monthly basis Alpha held formal meetings attended by representatives of all five of its departments to discuss trends and developments which might affect the needs of residents. However, the usefulness of such efforts was questionable because of perceptions outside of the procurement department, that procurement was solely an administrative or financial issue (interviewee, Alpha).

In Delta, communication between the Strategic Procurement Department and the Council’s four Directorates was formalised through meetings with the Procurement Board, that had representatives (Senior Managers) from each directorate, and a Practitioners Forum made up of procurement practitioners within each directorate. Such meetings took place on a quarterly basis and were supplemented by informal meetings. An identified challenge associated with procurement relationships was the threat of inertia. Interview data evidenced reluctance amongst some buyers to try new suppliers or procurement methods, which the interviewee of Alpha referred to as a syndrome:

‘Because it’s always been like that syndrome I call it, which is big in local government…trying to get people to change is the biggest nightmare.’

‘One of the biggest challenges I’ve got is to actually get these people to play the market and to see that it’s a big world out there.’

(Interviewee, Alpha)

Such reluctance to challenge or change procurement behaviour appeared to be at odds with the procurement rules that originated and were enforced by members of the ‘External Market’, and this had sometimes created further

tension between the council’s central procurement department and their ‘Internal’ market of buyers in Service Areas.

(Interviewee, Alpha).

Findings of Beta identified inertia and creeping complacency, which might stem from within the organisation as being potential hazards to effective procurement. The interviewee referred to this as a culture of ‘it’s always been done this way and explained how this can occur as legacy behaviour when procurement had been devolved to Service Areas and people ‘simply inherited a job’. He also reported that it often occurred due to a lack of challenge and that buyers would perceive good service without assessment: ‘I’ve heard it so many times; ‘worked with these people for years. We know we had a good service off them, and we’ll just go to them’. Well, when you test that statement, yes you’ve worked with them for years, but you don’t actually know that you’ve been getting a good service off them…I suppose that you probably did in the first early days and years, but then the complacency, and the taking each other for granted steps in.

You’re at the seven year itch aren’t you? It’s just like any relationship in life, it starts to get a little bit, I suppose, taking each other for granted, and the effort isn’t there by the supplier anymore so much. He knows you’re going to come to him. Why should he chase you? You’ve got to reinvent your relationship periodically. And yeah, there is an awful lot of ‘we’ve always done it that way’, ‘we’ve always used that supplier’, because it’s easier.’

Key Relationships

Findings show there are often different simultaneous relationships with suppliers, particularly because of a demonstrated preference to procure internally, or from other councils with whom an external relationship also

exists, or from locally based suppliers who are also customers of their council. Furthermore, because of the requirement to achieve local community benefit there is encouragement for non-local suppliers to employ and train local residents, and for local firms to subcontract to them.

Figure 3 therefore emphasises the areas of overlap to a greater degree than any of the existing published RM frameworks. By analysing the different relationship types that exist with a particular stakeholder, it is possible to

position them within the framework. Within the scope depicted by Figure 3, relationships with important types of stakeholders can be identified as being of significance and shall be referred to as ‘Key Relationships’ (KR’s). The areas of overlap between markets were therefore found to be particularly interesting because of the dual or multiple types of relationships that can exist between a council and its key stakeholders.

KR-A: Customer relationships between a Council and its Residents

If the purpose of local government is to serve its residents using public money then KR-A should perhaps be at the heart of the RM model for local government procurement. Residents are thought of as being predominant in the customers market. However in some specific circumstances they can overlap in either or all of the external, internal or suppliers markets. A person resident within the council’s geographic boundaries exists within the customers market. It is possible to postulate reasonable assumptions regarding the involvement of residents in other relationships with their council. If this person is employed by the council, they may conceivably be involved with an internal market relationship. The person could alternatively work for an external organisation which supplies to the council, or work for an internal department which supplies other departments, and therefore involved in a supplier market relationship. Simultaneously, the person could be a member of a trade union or professional organisation

(external market). It is reasonable to assume that if this person is dissatisfied with a service which he or she is receiving, tension may occur between the internal relationship (as council employee) and the customer relationship (as a tax-paying resident).

There is a great deal of granularity within the customers market, which is dynamic, as evidenced by the three case studies Beta, Delta, and Gamma, that reported changing demographics. Residents may feasibly move in and out of a council’s boundaries, can be employed by or supply to the council, and as voters, they have political power.

When considering the needs of their residents, councils need to acknowledge that residents could be involved in any or all markets depicted in the framework model, although emphasis is on the customers market relationship in this context.

KR-B: Relationships between a Council and Suppliers

Council-supplier relationships are designated KR-B. The scope of council procurement is diverse and several types of supplier relationship are evident. Three variants are proposed to explain those that emerged as being of particular significance.

KR-B1: Suppliers based within the Local Economy

As KR-A shows, local businesses or third sector organisations are by definition local rates payers and generally employ residents. Because of this, they were often preferred by councils when selecting suppliers who perceived

that their selection helped achieve community benefit objectives.

Local suppliers can therefore exist within the customers and suppliers markets simultaneously, as depicted by the areas of overlap in the model.

An interesting related problem that emerged was that of buyer inertia; where legacy relationships had existed with established suppliers and with whom some sort of relationship had continued without sufficiently testing the market. This type of behaviour was at odds with the requirements for best value (BV) and value for money (VfM) and placed upon councils by higher tiers of government, and with other legal obligations, such as European procurement laws that were referred to by all cases.

KR-B2: Suppliers based outside the Local Economy

The local supplier market was a common theme within the findings and is of particular concern to councils, because of the simultaneous customers market relationships with the local economy and the duty of a council to achieve local or community benefit. Findings showed that councils can and do source from outside their local area where it is deemed beneficial to do so. It was therefore considered appropriate, to identify a second KR-B to represent external suppliers from outside of the local economy, as the nature of the relationship is slightly different, with a greater emphasis on the suppliers and less on the Customers market relationship. In some circumstances it was found that councils encouraged suppliers from outside of their local boundaries to contribute to community benefit, for example by awarding contracts to suppliers that agreed to employ local residents.

A further point of interest is that in some instances a simultaneous external market relationship with a supplier exists. Organisations such as The Fairtrade Foundation and its associated Fairtrade brand which, having social and philanthropic objectives, operate as ‘influencers’ as well as ‘suppliers’; councils strived to optimise and prioritize their procurement of Fairtrade branded produce as a matter of policy.

KR-B3: Internal Suppliers

Another stakeholder group with whom there was more than one relationship was the group of internal departments within councils, who bought from and supplied to one another. In particular, the case study councils operated

devolved procurement but also had Corporate Procurements Units or equivalent vehicles. These units offered support and guidance to Service Areas and Departments, often involving legal services. In this way, the council provided a service to its internal stakeholders and therefore a supplier relationship existed. Service relationships were consultative and advisory whilst internal relationships were authoritative.

A lateral internal relationship was found to exist between different internal departments and, as indicated by the case studies; examples of interaction were apparent in the form of interdepartmental meetings to share knowledge relating to residents needs and procurement issues.

In instances of internal supply the providers received services as a customer from other internal departments, including Corporate Procurement Units, meaning that multiple simultaneous relationships between the council and its in-house supplier existed. KR-B3 can therefore be placed in the model, within the area of overlap between the customers, suppliers and internal markets.

KR-C: Relationships between a Council, Higher Tiers of Government, and the Legal System

Higher tiers of government and the legal framework were found to be significant stakeholders within the external market. Both the European Community and UK Central Government provide external influence on both customers and suppliers in the form of governance, guidance and funding.

Cases evidenced the influence of procurement rules and regulations on their behaviour and propensity to develop relationships. The requirements for fixed-term contracts as well as other rules were in place to ensure that councils’ procurement behaviour demonstrated the achievement of the best value for money in the interest of the customers market, i.e. the general public.

Official government publications show that councils were encouraged to engage in both partnership and collaboration by central government as part of the National Procurement Strategy and the VFM agenda.

KR-D: Relationships between a Council and its Collaborators and Partners

Partnerships involved joint working with other councils or the private sector to achieve improved costs and service delivery. Partnerships with private sector firms were typically used in building works or construction.

Collaborative partnerships with other councils were also important to councils, and occurred with either or both customers or suppliers. Typical forms of collaboration were supply through collective frameworks and service provision for and on behalf of other councils. As mentioned, such arrangements are strongly encouraged by higher tiers of government and are proposed for mutual advantage, with an emphasis on sharing risks and benefits. In this sense, these types of relationships were found to exist within the overlap between the customers and suppliers markets, and with the external market; in instances where the relationship involved joint working with other councils or other public organisations, such as for the administration of pension schemes, collaborative purchasing, framework agreements, or for e-Procurement.

An important point is that KR-D should be thought of as being a broader umbrella ‘relationship within which KR-B could exist. To illustrate, it was found that partnerships existed with national firms that had undertaken targeted recruitment and training of local residents. These partnerships therefore involved KR-B2.

Conclusion: The Scope of Relationship Marketing Theory for Local Government Procurement

This study has mapped and modelled the scope of relationships specifically for local government procurement, and identified a series of key relationships to which local authorities should pay particular attention. Used in conjunction with the stakeholder planning process suggested by Bryson (2004), it will enable them to visualise clearly the broad scope of procurement, and how the relationships between councils and suppliers are in fact part of a wider and interlocking network of relationships. For example, this will enable a structured approach to brainstorming the list of potential stakeholders at the ‘organizing participation’ stage early in the process.

This study should also be useful to policy makers concerned with improving the long-term effectiveness and efficiency of local government procurement. Awareness will also help officers, including junior and less experienced buyers and those outside of the procurement department, to better understand who their stakeholders are. In turn, this will help councils to overcoming distance relationships between themselves and stakeholders, particularly residents, with whom multiple types of relationship can exist.

Further research should now be undertaken to test the model in other geographic contexts. There is a need to test empirically the notion of causal links between awareness and emphasis on establishing and developing long-term relationships with the four main stakeholder categories, and with the seven key relationships identified by this study. Additionally, empirical research should be undertaken to explore and test the proposed link between relational approaches to procurement, and variables including local government performance, resident satisfaction, and economic indicators.

REFERENCES

Agranoff, R. and McGuire, M. (2004) Collaborative Public Management: New Strategies for Local Governments, Georgetown University Press,Washington DC.

Andrews, R., Boyne, G.A., Law, J. and Walker, R.M. (2005) ‘External constraints on local service standards: the case of comprehensive performance assessment in English local government’, Public Administration, 83:3, pp.639-656.

Andrews, R., Esteve, M. and Ysa, T. (2015) ‘Public-private joint ventures: mixing oil and water?’Public Money and Management, 35:4, pp.265-272.

Bovaird, T. (2006) ‘Developing new forms of partnership with the ‘market’ in the procurement of public services’, Public Administration, 84:1, pp.81-102.

Bryson, J.M. (2004) ‘What to do when stakeholders matter’ Public Management Review, 6:1, pp.21-53.

Chandler, J.D. and Vargo, S.L. (2011) ‘Contextualization and value-in-context: How context frames exchange’, Marketing Theory, 11:1, pp.35-49.

Clarkson, R.M., Clarke-Hill, C. and Robinson, T. (1997) ‘Towards A General Framework For Relationship Marketing: A Literature Review’, Unpublished paper presented at the Academy of Marketing Conference, July 1997, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK.

DCLG (2014) Local Authority Revenue Expenditure and Financing: 2014-15 Budget, England (revised), Department for Communities and Local Government, London, UK.

Doherty, B. (2012) ‘The Role of Social Enterprise in UK Local Economic Partnership Areas (LEPs)’, Conference Paper for the Institute for Small Business and Entrepreneurship (ISBE), 7-8 November 2012, Dublin:Ireland.

Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989) ‘Building theories from case study research’, Academy of Management Review, 14:4, pp.532-550.

Gillett, AG (2015) ‘REMARKOR: Relationship Marketing Orientation on local government performance’, Journal of Services Research, 15:1, pp.97-130.

Godson, M. (2009) Relationship Marketing, Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press. Great Britain Local Government Act 2000. Available at: <URL: http://www.opsi.gov.uk/ Acts/acts2000/ukpga_20000022_en_1>.

Great Britain Localism Act (2011) Available at: <URL: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ ukpga/2011/20/contents/enacted>.

Great Britain Public Services (Social Value) Act (2012) Available at: <URL: http://www. legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/3/pdfs/ukpga_20120003_en.pdf>

Grönroos, C. (2000a) ‘RM – The Nordic School Perspective’ in J Sheth and A Parvatiyar (eds.) Handbook of Relationship Marketing, Sage Publications Ltd, London, UK, pp.96-116.

Grönroos, C. (2000b) Service Management and Marketing: A Customer Relationship Management Approach, Wiley, New York, NY.

Grönroos, C. (2006) ‘What can a service logic offer marketing theory?’ in RF Lusch and S L Vargo, (eds), The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing. Sharpe Inc, Armonk, NY, pp.354-364.

Grönroos, C. (2007) Service Management and Marketing, 3rdedn, Wiley, Chichester, UK.

Grönroos, C. (2011) ‘A Service Perspective on Business Relationships: The Value Creation, Interaction and Marketing Interface’. Industrial Marketing Management, 40:2, pp.240-247.

Gummesson, E. (1994) ‘Making relationship marketing operational’, International Journal of Service Industry Management, 5:5, pp.5-20.

Gummesson, E. (2002) Total Relationship Marketing: Marketing Strategy Moving From the 4Ps – Product, Price, Promotion, Place – of Traditional Marketing Management to the 30 Rs. – The Thirty Relationships – of a New Marketing Paradigm, (2ndedn) Butterworth-Heinemann,Oxford, UK.

Gummesson, E. (2008a) Total Relationship Marketing, (3rdedn), Butterworth-Heinemann Oxford, UK.

Gummesson, E. (2008b) ‘Case Study’ in R Thorpe and R Holt (eds) The SAGE Dictionary of Qualitative Management Research, Sage Publications Ltd, London, UK, pp.38-40.

Healey, J. and Milton, S (2008) ‘Foreword’ in DCLG (Department for Communities and Local Government) (2008) The National Procurement Strategy for Local Government – Final Report ‘Towards public service transformation’. Communities and Local Government Publications, London, UK: p.4.

Hedges, A. (1985) ‘Group Interviewing’, in R. Walker (ed), Applied Qualitative Research, Gower, Aldershot, UK: pp.71-91.

Hunt, S.D. and Morgan, R.M. (1994) ‘Relationship marketing in the era of network competition’, Marketing Management, 3:1, pp.18-27.

Jost, G., Dawson, M., and Shaw, D. (2005) ‘Private Sector Consortia Working for a Public Sector Client – Factors that Build Successful Relationships: Lessons from the UK’. European Management Journal, 23:3, pp.336-350.

Khan, S. and Schroder, B. (2009) ‘Use of rules in decision-making in government outsourcing’, Industrial Marketing Management, 38:4, pp.379-386

Kotler, P. (1992) ‘It’s Time for Total Marketing’, Business Week Advance, Executive Brief, 2.

Kotler, P. (1994) Marketing Management : analysis, planning, implementation and control, 8thedn, Prentice Hall International, London, UK.

Martin, M. (2002) ‘The modernization of UK local Government: Markets, managers, monitors and mixed fortunes’. Public Management Review, 4:3, pp. 291-307.

McGuire, L. (2012) ‘Slippery Concepts in Context’. Public Management Review, 14:4, pp. 541-555.

McLaughlin, K., Osborne, S.P. and Chew, C. 2009 ‘Relationship Marketing, RelationalCapital and the Future of Marketing in Public Service Organizations’. Public Money & Management, 29:1, pp. 35-42.

Morgan, R.M. and Hunt, S.D. (1994) ‘The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship

Marketing’. Journal of Marketing, 58:3, pp. 20-38. N.A.O. (National Audit Office) and Audit Commission, (2010) A Review of Collaborative Procurement Across the Public Sector, National Audit Office, London, UK.

O.G.C. (Office of Government Commerce) (2008) An Introduction to Public Procurement, Office of Government Commerce, London, UK.

Osborne, S.P. (2010) ‘Delivering Public Services: Time for a New Theory?’Public Management Review, 12:1, pp. 1-10.

Osborne, S.P., Radnor, Z. and Nasi, G. (2013) ‘A New Theory for Public Service Management? Toward a (Public) Service-Dominant Approach’, The American Review of Public Administration, 43:2, pp. 135-138.

Osborne, S.P., Radnor, Z., Vidal, I. and Kinder, T. (2014) ‘A sustainable business model for Public Service Organizations?’Public Management Review, 16:2, pp. 165-172.

Perry, C. (1998) ‘Processes of a case study methodology for postgraduate research in marketing’, European Journal of Marketing and New Zealand Journal of Business, 32:9/10, pp. 785-802.

Radnor, Z. and Osborne, S.P. (2013) ‘Lean: A Failed Theory for Public Services?’Public Management Review, 15:2, pp. 265-287.

The Conservative Party (2010) Big Society Not Big Government. The Conservative Party, London, UK.

Trochim, WMK (2006) Unit of Analysis. Available online at: <URL: http://www. socialresearchmethods.net/kb/unitanal.php>

United We Serve, (2013) available online: <URL: http://serve.gov/council_home.asp>

Vargo, S.L. and Lusch, R. (2004) ‘Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing’. The Journal of Marketing, 68:1, pp. 1-17.

Vargo, S.L. and Lusch, R. (2008) ‘Service-Dominant Logic: Continuing the Evolution’. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36:1, pp. 1-10.

Vargo, S.L. and Lusch, R. (2011) ‘Service-Dominant Logic: a Necessary Step’. European Journal of Marketing, 45:7/8, pp. 1298 – 1309.

Yin, R.K. (2003) Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 3rd edn, Sage Publications Inc, Thousand Oaks, California.

Dr. Alex G. Gillett is Lecturer in Marketing at The York Management School, University of York, Heslington, United Kingdom. Email: doctoralexgillett@

gmail.com.