An Analysis Of Interactions Among The Variables Of Cost Of Conflict Amongst Nations

The purpose of this paper is to determine the cost of conflict measurement variables and their relationships, on which the top economists and policy makers should focus, so as to make good judgment of all the losses that can be brought about by war. In this paper, an Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) based approach has been employed to model the cost of conflict variables. These variables have been selected after extensive research of available resources on this topic. These variables have been tested to determine which ones are most harmed, which means that they have influence on both financial as well as overall well being of the nation’s population. The paper highlights the variables associated with the cost of conflict and the various relationships between the affected variables. An interesting finding of this paper is, that some of the damages of war which are generally considered to have high impact financial effects do not do so and others do, such as war duration. Also in this paper, an interpretation of cost of conflict variables in terms of their impact and dependence powers has been carried out. As of now, the researchers have not been able to find out any other research done in this particular facet of war, which implements ISM.

INTRODUCTION

We live in very turbulent times today. The Indian neighbors i.e. the South Asian countries namely Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Iran, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka are sitting on a time bomb, and have been trying to find ways and excuses to get back at each other for a long time. War should be understood as an actual, intentional and widespread armed conflict between political communities according to the Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy.

The United States for example, has waged seven major interstate wars since 1900, making it one of the most frequent participants in major wars over the last century. America’s combined military and civilian losses in these seven conflicts totaled approximately 620,000 dead, roughly the same number that Iran suffered in its war with Iraq (between 450,000 and 730,000), the only interstate war Iran fought in this entire period.

Closer home we have India and Pakistan which are perhaps the most dangerous neighbors on the globe”, and given that both countries are now nuclear powers. They have within living memory fought three major wars, and continue in a state of perpetual tension. South Asia is home to well over one fifth of the world’s population, making it both the most populous and the most densely populated geographical region in the world. A war here would mean unbelievable death and destruction.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In this section we discuss the various studies related to the factors of conflict, study of war as a game, and the interrelation between the factors affecting the cost of war. Polachek and Xiang (2010) broadly discussed the different aspects on trade gains and losses before and after the war, and how in an incomplete information game nations protect gains from trade by avoiding belligerence and maintaining peace. A comprehensive analysis using separate OLS regression equations for civilian and military losses on the cost of conflict,t was conducted by various authors like Benjamin Paul and Sarah E. Croco (2010) in the paper “Bear Any Burden? How Democracies Minimize the Costs of War”. The factor of conscription has been dealt with separately by Horowitz and Levendusky (2011), where they have tried to support warfare. From these review papers, one can develop a holistic idea of the cost of conflict and how the damage under various headings changes in different scenarios Charan et.al, (2008).

The popular theme followed while developing an idea around conflict, has been the bargaining theory of conflict. The bargaining literature contains a plethora of models that have offered important insights following this approach. Polachek and Xiang (2010) have also used a simple crisis bargaining game, to show how opportunity costs associated with economic interdependence generate a lower equilibrium probability of war. This means that more the benefits of trade there is, less and less chance of actual conflict exist. Robert Higgs (2008) in caging the dogs of war makes an effort to talk about the perils of the war, by focussing on the Iraq, Korean and Vietnam wars among others, and observe how war is a continuation of politics by other means. The USD 3 trillion Iraq war is taken again as the centerpiece in Stiglitz and Bilmes (2008) note, at it focuses on the difference between the governments cash accounting basis and a more rational accrual basis of accounting. Such practices are widely used in the business world, and take into account future obligations when they are incurred rather than the moment they are actually spent down the road. Faisal et al.( 2007); Jharkharia and Shankar,(2005); Glick and Taylor in (2010), Sanchez, (2009) using econometric methods, found a very strong impact of war on trade volumes and they are consistent even after many years of the war ending. They have analyzed extensive literature and say, that many researches have also been concerned with the putative reverse causation i.e. the effect of trade (along with other political variables) on the likelihood of conflict among countries. They use gravity models such as benchmarks from which to assess the trade impact of economic disturbances and policy regimes, which are different from the bargaining model of conflict.

Over 70 countries have experienced civil war since World War II, as analyzed by Fearon and Laitin (2003). In 2004, world military spending was over USD 1 trillion , about 2.6% of the world’s gross domestic product stated SIPRI (2005). Journalistic reports argue, that organized crime accounts for one-fifth of the world’s GDP observed Glenny (2008). Also, the probability of conflict even if it never takes place, can have a powerful negative influence on investment, trade, and economic growth. Garfinkel and Skaperdas (2008) and Gonzalez (2010), have developed theoretical models that take account of the various negative economic effects of conflict. Though difficult to identify, some of the studies reviewed by Stergios Skaperdas (2011) in “The Costs Of Organized Violence: A Review Of The Evidence”, attempt to capture these negative effects of conflict that may never actually take place.

COLLECTION OF DATA

Primary data for the research was collected based on the responses received from the defense personnel. A questionnaire was prepared based on the elements which appeared to be related to the cost of conflict, after reviewing the papers studied. After that a list of the elements was given to various experts from the defense field. They were asked to individually select out 25 given elements which were thought to be related to the cost of conflict. The response was procured after a brief presentation was made in their presence at IIM Indore April 2012. In this brief meeting, they were explained the topic, its aims, how to fill the questionnaire pertaining to selection of variables and how to determine the relationship between the variables selected for the study. The mean years of service served by the 12 respondents were 16 years, and the designation ranged from Major to Lieutenant Commander to Staff Pilot. Within a period of 5 days, the most pressing variables were identified. Systematically experts were asked about the mutual relationship amongst these variables via a second questionnaire. The variables were selected on the basis of the tabulation carried out from the responses.

Secondary data was collected from various research papers and articles pertaining to the factors,that would be chosen to be studied for implementing the methodology.

METHODOLOGY

ISM was used for collecting and identifying relationships among specific elements, which define a problem or an issue suggested by Warfield (1974), Malone,(1975). Singh et.al, (2007), Mandal and Deshmukh (1994); Jharkharia and Shankar (2005) pointed out, that it provides us with a means by which correct order can be developed on the relationship of such elements. This section deals with discussion of the ISM methodology.

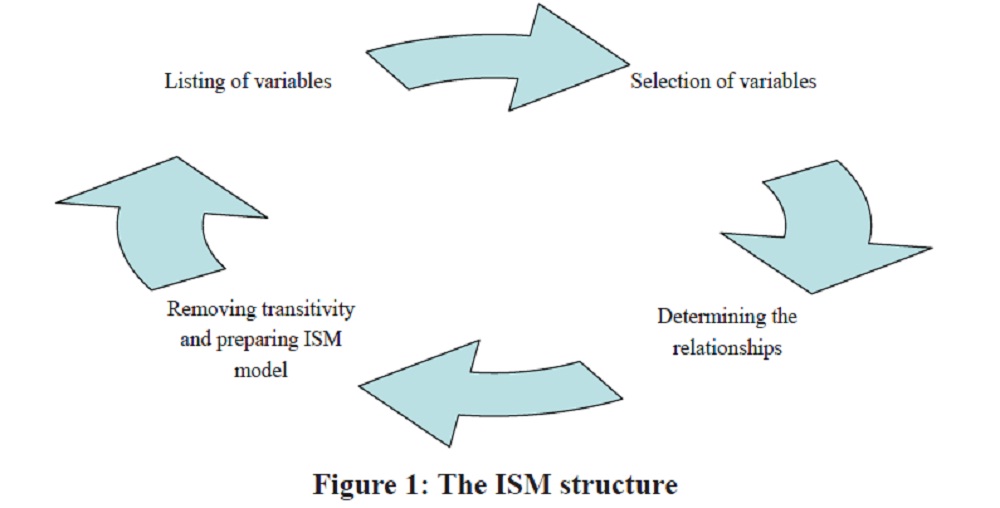

The various steps involved in the ISM technique are as follows (Venkatesan, 1979):

1. Elements affecting the system under consideration are listed, which can be objectives, actions, individuals, etc.

2. From the elements identified in Step 1, a contextual relationship is established among variables with respect to which pairs of variables would be examined.

3. A structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM) is developed for elements, which indicates pairwise relationships among elements of the system under consideration.

4. A reachability matrix is developed from the SSIM, and the matrix is checked for transitivity. The transitivity of the contextual relation is a basic assumption made in ISM. It states that if a variable A is related to B, and B is related to C, then A is necessarily related to C.

5. The reachability matrix obtained in Step 4 is partitioned into different levels.

6. Based on the relationships given above in the reachability matrix,

a directed graph is drawn and the transitive links are removed.

7. The resultant directed graph is converted into an ISM, by replacing variable nodes with statements.

8. The ISM model developed in Step 7 is reviewed to check for conceptual inconsistencies and necessary modifications are made.

Reachability Matrix

The SSIM is then converted into a binary matrix, called the reachability matrix by substituting X, A, V and O by 1 and 0 according to the accepted methodology (Thakkar et al., 2006). Then its transitivity is checked. If element i leads to element j and element j leads to element k, then element i should also lead to element k. By incorporating transitivity, the modified reachability matrix is obtained Bolanos et al., (2005), Thakkar et al. (2008).

Identification of Elements

Elements chosen for studying relevance to the cost of conflict

1. Learning faster than the competition. (Emerald Article: Learning faster than the competition: war games give the advantage (Chussil, 2007)

2. Irrevocable decisions. (Armed Confrontations, Irrevocable Decisions, and Stability in Conflict (Luterbacher, 1975)

3. Likelihood of conflict among countries.

4. Prospects for future peace and prosperity. (Bailes,2005)

5. Natural resources of the attacked nation. 6. Natural resources of the attacking nation.

7. Religious difference between the ruling party of attacking nation and the dominant religion of the attacked nation.

8. gains from trade before the war (Opportunity Costs and the Probability of War in an Incomplete Information Game (With Comments by Lloyd Jeff Dumas Solomon W. Polachek and Jun Xiang) (Polachek and Xiang, 2010)

9. Presence of democracies in the attacking nation*

10. Presence of democracy in the nation being attacked *

11. National Military Capabilities*

12. Coalition Capabilities*

13. Guerrilla/Attrition Strategy*

14. Battle Proximity*

15. War Duration*

16. Initiator*

17. High Adversary War Aims*

18. Population*

19. Conscription (Drafting Support for War: Conscription and Mass Support for Warfare Michael C. Horowitz University of Pennsylvania

Matthew S. Levendusky University of Pennsylvania) (Horowitz and Levendusky, 2011)

20. Occupation*

21. Regime-Type*

22. Relative GDP*

23. Learning From Past*

24. Adversary’s War Aims*

25. Adversary’s Strategy*

*indicates the variable has been taken from the paper Valentino et al.,(2010)

Analysis

After the exercise of distributing the questionnaires and the task of recording the responses was done, 15 factors selected came out to be strongly related to the cost of conflict. After these variables were found out, the relations between them were determined. These relations were filled out according to the following assumptions : The relation of one variable to other would be analyzed considering first the point of view of the attacking nation, and then that of the attacked nation.

For the purpose of inquiry it was also important to analyze if one variable be increased or decreased in one country and how that would affect the other variable while considering it to be of a different country. For the purpose of illustration, if we consider the natural resources of the attacking nation and the adversary’s strategy, then there is a relation between the two; wherein the former affects the latter. Hence the relationship letter filled would be A, because if the natural resources of the attacking nation are something that the attacked nation will need if it can defeat it in battle then it would not target to destroy them and hence that would decrease the cost of battle and hence the adversary strategy is affected.

The below list shows the selected variables in the order of their scores which were obtained from the responses.

1. War duration

2. Regime type

3. National military capabilities

4. Relative GDP

5. Learning from the past

6. Adversary’s strategy

7. Likelihood of conflict amongst countries

8. Natural resources of the attacked nation.

9. Coalition capabilities

10. Guerrilla andattrition strategy

11. Battle proximity

12. Adversary’s war aims

13. Learning faster than the competition

14. Natural resources of the attacking nation

15. Gains from trade before the war

There were the 10 elements which the participants rejected, when told to select only 15 relevant variables for determining relationships to the cost of conflict. This also produces certain interesting results. For example we can see that factors like the population, presence of democracies in the attacking nation, religious differences between the attacking nations which would traditionally in the common sense be considered to be affecting the intensity of the war, and in turn the damage which would affect the cost of conflict, have not been considered important.

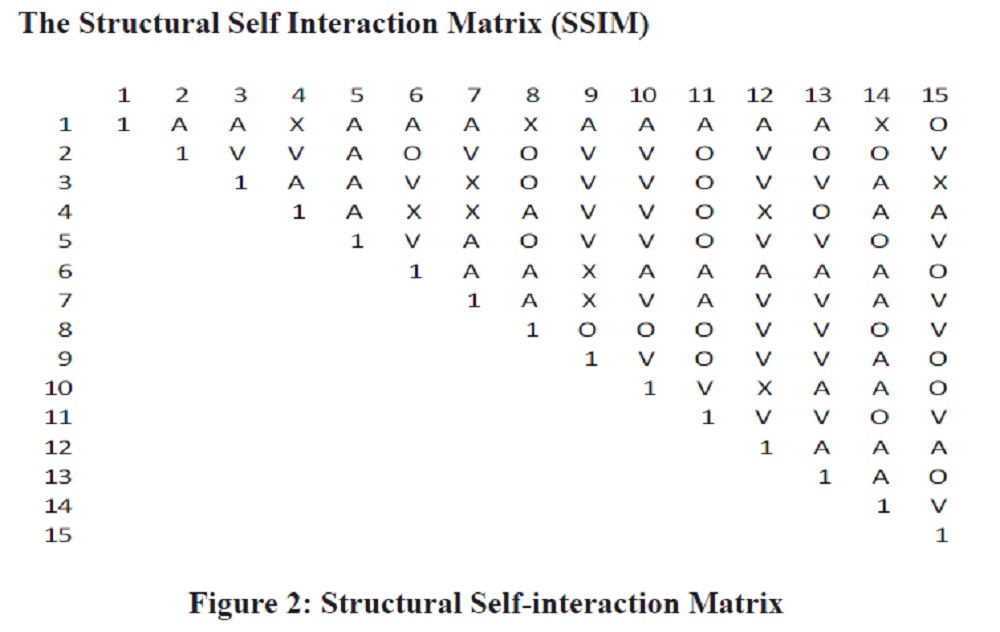

The SSIM is the step in which we take the opinions from experts in a collective and discussed manner (Watson, 1978). In the above Figure 2 we provide the SSIM for this study. The SSIM helps us understand that there are many direct true relationships between the variables. This is good because it means that our variables are capturing the subject.

The Reachability matrix and the levels of Criterian

The reachability matrix is important in converting the opinions of experts into a more quantitative form. The above given figure 3 with the final reachability matrix for this study. The reachability matrix helps us understand that there is clear split along the variables. This means that they do not overlap. Hence the variables are capturing the different dimensions of the subject properly.

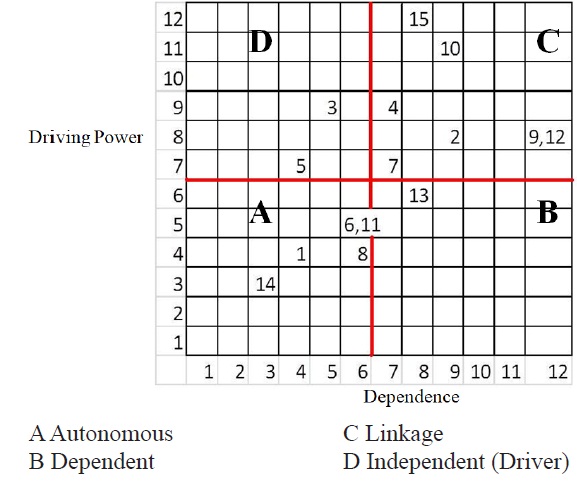

Figure 4: Driver Power Dependence Matrix

Driver power dependence matrix is important to visually release the variables relation to each other. The above given Figure 4 with the driver power and dependence matrix for this study. The ABCD notation can be explained with the help of the following A Autonomous, B Dependent, C Linkage and D Independent. The driver dependence matrix helps us understand that there are only few variables which have high driving power. This is good because to create an efficient change in the subject the decision makers can address these variables and be more relaxed in managing the others.

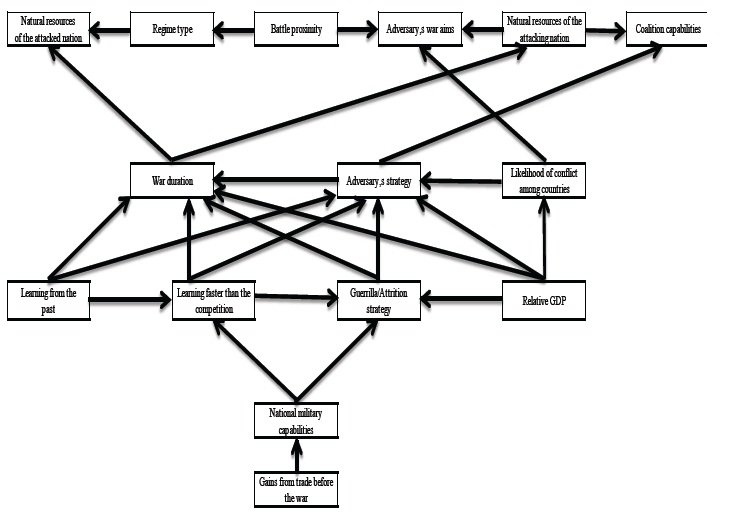

The Interpretive Structural Model (ISM) for Measuring the Cost of Conflict

The ISM model is the main finding of this study. Below in Figure 5 we provide the ISM model.

CONCLUSION

The aim of any ISM model in the end is to find out the relationship between the variables affecting the issue that has been taken up for the study, and the various inter-relationships between them. Below are the findings of the study:

1. Ranks of the criteria based on their driver powers indicate that gains from trade before the war is the key criterion. Next are the guerrilla,attrition strategy, national military capabilities and relative GDP.

2. From the map, it is seen that the natural resources of the attacked nation, the natural resources of the attacking nation, regime type, battle proximity, adversary’s war aims and coalition capabilities are the top level criteria. War duration, adversary’s strategy and likelihood of conflict among countries are the second level criteria. The remaining criteria are placed in the bottom levels.

3. Driver power dependence matrix reveals that natural resources of the attacked nation, natural resources of the attacking nation, war duration, and battle proximity are the autonomous variables in the vendor selection process. These variables are weak dependents and are relatively disconnected from the system except, for adversary

strategy which is also a weak driver.

4. Dependent variable is learning faster than the competition. This attribute is a weak driver but strongly dependent. 5. The following are the linkage variables which have strong driver power, as well as strong dependence likelihood of conflict among countries. Relative GDP, regime type, coalition capabilities, guerrilla/ attrition strategy, adversary’s war aims, and gains from trade before the war.

6. Variables like learning from the past and national military capabilities are the strong drivers. They condition the rest of the system and are called independent variables or drivers.

The above points hence let us get a better view of the dangers of war and conflict. These can be used by economists and other statisticians, to better understand and revise their models to account for the degree of significance that has been found to be related to the factors of the model. This also changes our view as to what previously was thought to be unimportant threats of war, which are very real and how the resources used to finance a war can and should be used more constructively used elsewhere.

REFERENCES

Archer, D., & Cameron, A. (2009) ‘Tough times call for collaborative leaders’, Industrial and Commercial Training, 41:5, pp.232-237.

Bailes, A.J. (Ed.). (2005) SIPRI Yearbook: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Bolanos, R., Fontela, E., Nenclares, A., & Pastor, P. (2005) ‘Using interpretive structural modelling in strategic decision-making groups’, Management Decision, 43:6, pp.877-895.

Charan, P., Shankar, R., & Baisya, R.K. (2008) ‘Analysis of interactions among the variables of supply chain performance measurement system implementation’, Business Process Management Journal, 14:4, pp.512-529. Chussil, M. (2007) ‘Learning faster than the competition: war games give the advantage’, Journal of Business Strategy, 28:1, pp.37-44.

Fearon, J. D., & Laitin, D. D. (2003) ‘Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war’, American political science review, 97:1, pp.75-90.

Garfinkel, M. R., & Skaperdas, S. (Eds.). (2011) The political economy of conflict and appropriation,

New York, Cambridge University Press.

Glenny, M. (2008) McMafia: A journey through the global underworld, Toronto, House of Anansi.

Glick, R., & Taylor, A.M. (2010) ‘Collateral damage: Trade disruption and the economic impact of war’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92:1, pp.102-127.

Higgs, R. (2008) ‘Caging the dogs of war: how major US neoimperialist wars end’, The Independent Review, pp.299-312.

Horowitz, M. C., & Levendusky, M.S. (2011) ‘Drafting support for war: Conscription an mass support for warfare’, The Journal of Politics, 73:2, pp.524-534.

Jharkharia, S., & Shankar, R. (2005) ‘IT-enablement of supply chains: understanding the barriers’, Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 18:1, pp.11-27.

Luterbacher, U. (1975) ‘Arms race models: where do we stand?’, European Journal of Political Research, 3:2, pp.199-217.

Malone, D.W. (1975) ‘An introduction to the application of interpretive structural modeling’, Proceedings of the IEEE, 63:3, pp.397-404.

Mandal, A., & Deshmukh, S.G. (1994) ‘Vendor selection using interpretive structural modelling (ISM)’, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 14:6, pp.52-59.

Nishat Faisal, M., Banwet, D.K., & Shankar, R. (2007) ‘Information risks management in supply chains: an assessment and mitigation framework’, Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 20:6, pp.677-699. Polachek, S.W., & Xiang, J. (2010) ‘Opportunity Costs and the Probability of War in an Incomplete Information Game (With Comments by Lloyd Jeff Dumas)’, Peace Economics, Peace Science, and Public Policy, 16:1, pp.1-6.

Polachek, S., & Xiang, J. (2010)2 ‘How opportunity costs decrease the probability of war in an incomplete information game’, International Organization, 64:1, pp.133-144.

Sánchez‐Pagés, S. (2009) ‘Conflict as a Part of the Bargaining Process’, The Economic Journal, 119:539, pp.1189-1207.

Singh, R.K., Garg, S.K., Deshmukh, S.G., & Kumar, M. (2007) ‘Modelling of critical success factors for implementation of AMTs’, Journal of Modelling in Management, 2:3, pp.232-250.

Skaperdas, S. (2011) ‘The costs of organized violence: a review of the evidence’, Economics of Governance, 12:1, pp.1-23.

Stiglitz, J.E., & Bilmes, L.J. (2012) Estimating the costs of war: Methodological issues, with applications to Iraq and Afghanistan, Oxford University Press, The Oxford Handbook of the Economics of Peace and Conflict, New York, pp.275-315.

Thakkar, J., Deshmukh, S.G., Gupta, A.D., & Shankar, R. (2006) ‘Development of a balanced scorecard: an integrated approach of interpretive structural modeling (ISM) and analytic network process (ANP)’, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 56:1, pp.25-59.

Thakkar, J., Kanda, A., & Deshmukh, S.G. (2008) ‘Interpretive structural modeling (ISM) of IT-enablers for Indian manufacturing SMEs’, Information Management & Computer Security, 16:2, pp.113-136.

Valentino, B.A., Huth, P.K., & Croco, S.E. (2010) ‘Bear any burden? How democracies minimize the costs of war’, The Journal of Politics, 72:2, pp.528-544.

Venkatesan, M. (1979) ‘An Alternate Approach to Transitive Coupling in ISM’, IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 9:3, pp.125-130.

Warfield, J. N. (1974) ‘Developing subsystem matrices in structural modeling’, IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 1, pp.74-80.

Watson, R. H. (1978) ‘Interpretive structural modeling—A useful tool for technology assessment?’, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 11:2, pp.165-185.

Dr. Malay R. Patel, Assistant Professor, Auro University, Surat, Gujarat, India. Email: malayrpatel@gmail.com.

Dr. Vimal Babu, Associate Professor, Symbiosis Institute of Business

Management, Pune (SIBM-Pune, India). Email: vimalsairam@gmail.com.

Umang Gupta, Research Scholar, Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee

(India).