A CHARACTERISTIC MODEL OF SUCCESSFUL WOMEN ENTREPRENEURS IN THE UK

The United Kingdom currently ranks at the bottom of the list compared to other high income countries with it’s percentages of female entrepreneurs. Because of this it loses out on valuable turnover and employment. The overall conclusion on the matter is that there is an overwhelming fear of failure by UK women. To counter this significant resources have been put in the market to encourage women to start their own companies. However all these resources focus on the first, six to eighteen months of start up and do not offer information on the resources needed to grow and sustain businesses. By introducing women with ways to be successful entrepreneur in the United Kingdom, this paper can provide them with the confidence they need to start, grow, and sustain a new venture.

INTRODUCTION

Female entrepreneurs are widely discussed in the United Kingdom. Surveys show that while a large percentage of UK women express a desire to start their own business only a small fraction of these actually go ahead (Brooksbank et-al., 2006). This puts the UK’s female entrepreneurs existence and growth rates, at the bottom of the list compared to other high income countries (Brooksbank et-al., 2006). As a result the UK loses out on thousands of small business start-ups which could bring in turnover, employment opportunities, and taxable profits. There has been a great deal of research done on this subject, specifically by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (Brooksbank et-al., 2006; Harding, 2004; Harding, 2003). The overall conclusion on the matter is that there is a greater sense of fear and failure by UK women that prevents them from pursuing their own start-ups (Brooksbank et-al., 2006). Initial research showed that there are an abundant resources throughout the United Kingdom available to women to get their own businesses started.

JUSTIFICATIONS OF THE STUDY

There currently exists a large gap in the research concerning successful female entrepreneurs as the information that is available lacks depth and longevity. A women interested in starting up a business can find advice on financing, distribution, suppliers, and marketing just to name a few. However, there is no readily available information for women proprietors on growing a business, ensuring its profitability, strategy and exiting. There is an obvious need therefore for research to be completed in this area.

Practically every book on entrepreneurship on the market contains a list of characteristics of successful entrepreneurs (Lambing and Kuehi, 2003; Kirby, 2003; Wickham, 2004). These books recognize that a successful entrepreneur will not be a mirror image of the traits they suggest but the books rather put forth their model as a foundation (Lambing and Kuehi, 2003; Wickham, 2004). However, none of these suggested frameworks consider the psychological differences between men and women. Therefore, there is an apparent need for more research to be completed on this subject.

Objectives of the Study

This paper aims at developing a model that describes successful female entrepreneurs and how they run their businesses. This character list will act as a confidence builder to remind females that they have the necessary characteristics to be successful. It will act as a momentum builder for those women whom are considering starting up entrepreneurial ventures. It will also act as a support tool for those women who may have already started up but need a reminder of what has and will make them. The focus of the research is on female entrepreneurs in the UK, who have successfully started a business and have been running the same for over five years. These are all small to medium sized companies with the majority located in the south east of England.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Entrepreneurs

There are around 3.8 million small enterprises (of all kinds) in the UK with less than 50 employees and under 60,000 enterprises with more than 50 employees. DTI, (2006) Microsoft founder Bill Gates is the

most likely person to be named as an inspiration or role model by UK entrepreneurs (DTI, 2006). Entrepreneurs are willing and ready to take a risk for profits. According to the National Federation of Independent Businesses, roughly half of all small businesses fail within five years of launching (Mucha, 2006). Most say that to avoid this fate, it takes the right combination of smarts, vision, instinct, and nerve (Mucha, 2006). Many of these personality traits are genetic but certainly successful entrepreneurs

work very hard to reach successful heights. Cochrane (2006) suggested that there are ten must-have characteristics of successful entrepreneurs. These are: (a) passion, (b) people, (c) core values, (d) learn form mistakes, (e) determination, (f) clear roles, (g) profit focus, (h) single-minded, (i) lead by example and (j) customer satisfaction.

Rogoff (2006) says that lucrative proprietors are simply thoughtful and attentive listeners. By being good listeners they allow the other person to feel comfortable about sharing information openly. This enables them to uncover the real issues of an entrepreneurial conversation quickly and respond to them productively. Pratt (2006) said that the difference between a successful entrepreneur and a bad one is their instinctive ability to avoid all things that are stereotyped. He suggests that too many people spend their time worrying about the things they are told they “should” worry about. For example, we often hear that for a business people are the best asset and therefore they “should” be trained. But Pratt argues that a successful entrepreneur knows what is best for the business.

Women Entrepreneurs

Women are half as likely to be involved in start-up activity as men (Harding, 2004). One third of the female population would start a business if it wasn’t for the fear of failure (Harding, 2003). Female entrepreneurs have a much lower expectation of the extent to which their companies would grow over a three year period from start-up. They expect that within 3 years their business will have a turnover approximately two fifths time higher than the turnover which was achieved in the first year. However men expect their businesses to be more than double the size in three years from startup (Harding, 2004). Amongst 22, high income countries, UK ranks 13th, with regards to the percentage of established entrepreneurial activity amongst men, UK, however ranks 21st, when it comes to established entrepreneurial activity amongst women (Brooksbank et-al., 2006). Women entrepreneurs are rarely a topic of entrepreneurship research (Baker et-al, 1997). Brush and Edelman (2000) propose that this may be because more similarities than differences have been found in past studies, hence the redundancy of further study. Thus, the background literature relating to the human, social and financial capital of women entrepreneurs, and especially nascent women entrepreneurs, is limited. Carter, et-al, (1997), studying 203 new firms in the retail industry, and found that “women-owned businesses were more likely to fail than those started by men. Women started on a smaller scale and made less use of previous

business experience. Home-based businesses, for example, are mostly owned by women”. Goffee and Scase (1985) in their book Women in Charge discuss the different types of female proprietors. They suggest that a woman’s belief in economic self-advancement, adherence to personal responsibility, and strong support for work ethic and profits will show her attachment to entrepreneurial ideals. In order to understand a woman’s attachment to conventional gender roles, one must look at that woman’s social position and life style.

Women’s’ Businesses

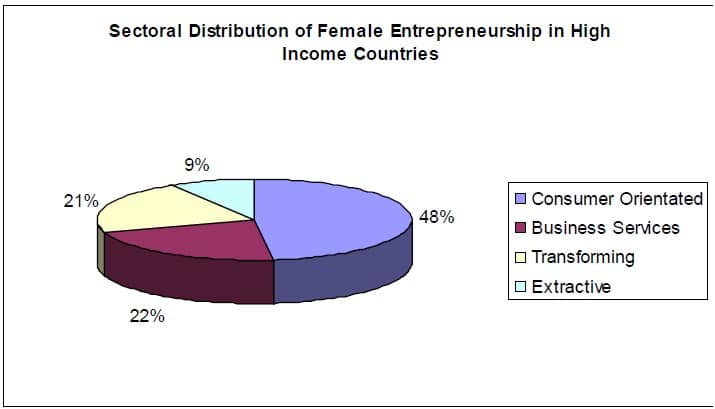

48% of female entrepreneurs own businesses in the service sector, compared with 36% of male entrepreneurs (DTI, 2006). Numerous studies have shown that female-controlled businesses are more likely to be found in the retail and service sectors (Charboneau, 1981; Hisrich, 1989; Hisrich and Brush, 1984; Hisrich and O’Brien, 1981, 1982; Humphreys and McClung, 1981; Sexton and Smilor, 1986; Welsh, 1988). Often businesses run by women fall in the arena of professions that “help” (Wojahn, 1986).

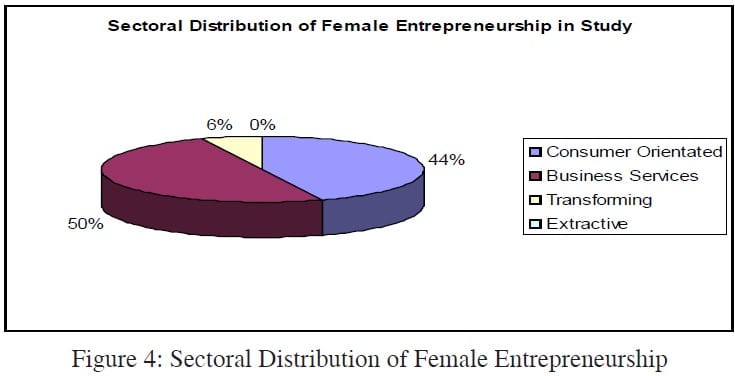

While some female start-ups are found in such areas as agriculture, forestry, construction and manufacturing (Hisrich and O’Brien, 1981), these are considered non-traditional areas for women in business (Catley et-al, 1998). However, Gracie (1998) says that the picture of women in the entrepreneurial sector is changing rapidly. Industry choice influences the size of a business as well as growth. These traditional female industries generally require less initial capital to enter and offer a relatively low return on investment (Humphreys and McClung, 1981). This is confirmed by Wojahn (1986) who notes that female-owned businesses have both lower profits and slower growth rates than those owned by men. In the most recent study completed in the Global Entrepreneurial Report we can

see the breakdown of what type of businesses women proprietors are most prevalent in (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Report, 2006). The four sectoral groups of women entrepreneurship comprise of: (a) Consumer Orientated (b) Business Services (c) Transformation and (d) Extraction

Figure 1: Spectral Distribution of Female Entrepreneurship

Source: Global Entrepreneurial Report, 2006

Motivation

54% of women start a business so they can choose what hours they work, compared to only 35% of men. (prowess database, 2006) and 21% of women state family commitments as a reason for becoming self-employed compared to only 2% of men. (DTI Data base, 2006) Although independence is stated as the primary goal of a start-up, 45% of women, in the recent Women in Business Survey (2000) conducted by Barclays Bank stated financial growth as their main motive, after the business’s successful initial years. The element of self-control and self worth involved in entrepreneurship is still a big motivator for women. They want to have that financial self sufficiency” (Klein, 2006). It has been suggested that women are motivated by the social contribution, their businesses can make to society (Orhan and Scott, 2001). According to Still and Timms (2000) women start their own businesses, with the objective of “making a difference” They are more client-focused than men (Brush, 1992), more ethical in operations and make a social contribution in addition to pursuing economic motives (Bell et-al, 2005). Goffee et-al. (1982) found that some women had put forth a deeper social reason which was, their intent of “doing their thing” to avoid male dominance in their lives. Welsh (1988) and Carter and Cannon (1988) also found evidence of a “glass ceiling” effect pushing women from management positions into their own business. Also many researchers found that women start businesses for the same basic reasons as apply to male founders (Cromie, 1987; Goffee and Scase, 1983; Schreier, 1975).

Lifestyle

80% of women compared with 17% of men are responsible for looking after the children or arranging childcare facilities (Barclays 2000). The costs of child care can be higher for business owners who have no option but to work flexibly and travel to develop their business. But unlike other essential business costs, caring is not tax deductible. (prowess, 2006). The most entrepreneurial age group for females is 35-44 years (2004). Recent research has sought to develop a greater understanding of the underlying career goals of men and women and how that relates to family obligations and flexibility. Several researchers conclude that autonomy and flexibility to focus on family needs persuade many women to start their own business (DeMartino and Barbato, 2003) and women used the autonomy of entrepreneurship to integrate the goals of family and personal interests to the goals of work. According to another study, two-thirds of female entrepreneurs structured their enterprises around their personal

life, compared to only 15% of men (Bailyn, 1993).

Finance

A study of 300 male-owned and 300 female-owned businesses in the U.K. found a significant difference regarding the amount of start-up capital, with women reporting lower start-up capital than men, which could have a long-term effect on business growth and success. (Carter and Rosa, 1998). On average, the median start up financing for men is £18,000 of which they invest £10,000 while for women the start up finance is £10,000 of which they invest £7,616 (Harding, 2004). It is worth noting that many of the women who are in business today have built their businesses organically, without venture capital or stock-market listing and with a fairly minimal use of bank loans. Many women entrepreneurs openly boast that they never had to take a loan or sell a single share in their business (Gracie, 1998). The biggest impediment to women’s growth is the lack of access to information about how to get more capital (Klein, 2006).

Education and Experience

Women with school enterprise training are more than twice as likely to be involved with a nascent business (1.8% without training and 4.6% with). (Harding, 2004). Overall enterprise training at college or university nearly doubles the likelihood that an individual will be involved in entrepreneurial activity (Harding, 2004). The majority of women business owners come from professional areas and have had some tertiary education (Hisrich and O’Brien, 1981, 1982; Humphreys and McClung, 1981; Stevenson, 1986). In comparative studies they appear better educated than the typical male entrepreneur (Carter and Cannon, 1988; Watkins and Watkins, 1984) yet appear to lack self-confidence (Birley, 1989). The role of previous work experience is seen as crucial in incubating future entrepreneurs. Welsch (1988) observed that women owners had less business experience than their male counterparts.

Culture

Harding (2004) reveals that, women are more likely to be involved with starting up socially oriented activities (4.9% of women compared to 4.5% of men) but are less likely to be owners or managers of a social venture (6.2% of women compared to 7.7% of men). Women’s enterprises have been responsible for the development of a new business culture where pursuit of profit is not the objective. (Gracie, 1998) Aileen Gorman, executive director of the Commonwealth Institute says men and women are going about their leadership roles in different ways, “Women really seemed to be focused on not just the bottom line, but also the culture within a company” (Hurst, 2005). Relationship building comes up again and again when women describe their success (Fisher, 2004).

Psychological Characteristics

Both male and female entrepreneurs show stronger personality traits than their management counterparts although there are not significant differences between entrepreneurs by sex with regard to these characteristics. These findings are consistent with the classic portrait of an entrepreneur but also

demonstrate that the traits apply equally to women (Catley and Hamilton, 1998). Cromie (1987) used psychometric scales to analyze the following seven characteristics of male and female business owners (a) need for achievement, (b) independence, (c) locus of control, (d) planning, (e) primacy of business, (f) achievement and (i) trust In each case there was no significant difference between male and females. Humphreys and McClung (1981) found that both sexes defined job satisfaction in the same terms (personal achievement and being their own boss) with extrinsic factors being less important. Hisrich and O’Brien (1981) found men and women founders to both, have high need for achievement which they related to the formation of their own businesses. Welsch and Young (1984) also found no differences in personality characteristics between male and female entrepreneurs or in the problems they faced. The work by Buttner and Rosen (1992) is interesting because it found that, although women business owners seem to have the same qualities as men, stereotypes about their beliefs and perceptions indicated they were thought to be lacking the characteristics needed for successful entrepreneurship. Thus women are perceived as being less successful than their male counterparts.

METHODOLOGY

The objective of this research is to provide a framework of characteristics that help describe a successful female entrepreneur in the United Kingdom. Content analysis method had been used to build the framework. This simple method is good for analyzing text and pulling out common themes. interviews were then completed as part of the primary research. Secondary research was also conducted in order to expand the number of subjects in the analysis.

Content Analysis

Content Analysis is a family of procedures for studying the contents and themes of written or transcribed text. It is a qualitative method used to analyze communications such as letters, memoranda, speeches, interview transcripts, and article abstracts (Insch and Moore, 1997; Flick, 1998). The purpose of content analysis in this paper is to identify intentions and other characteristics of the communicators. An appealing aspect of content analysis is that it is relatively unobtrusive and therefore unlikely to be subject to reactivity bias. It also has the potential for an extremely high reliability of measurement (lnsch and Moore, 1997). Weaknesses and potential areas of concern in the use of content analysis generally relate to the biases that can be introduced through the values and interests of the researcher and the difficulties encountered in extracting data from contextually rich communications. (Insch and Moore, 1997). The procedure used is based on a scaled down version of a synthesis of recommendations regarding the use of content analysis from Weber (1990), Krippendorff (1980), and Merritt (1970). The procedure consists of five steps which are (a) identify the questions to be investigated and the constructs involved, (b) identify the texts to be examined, (c) specify the unit of analysis, (d) keyword analysis and finally (e) specify the categories.

Interviews

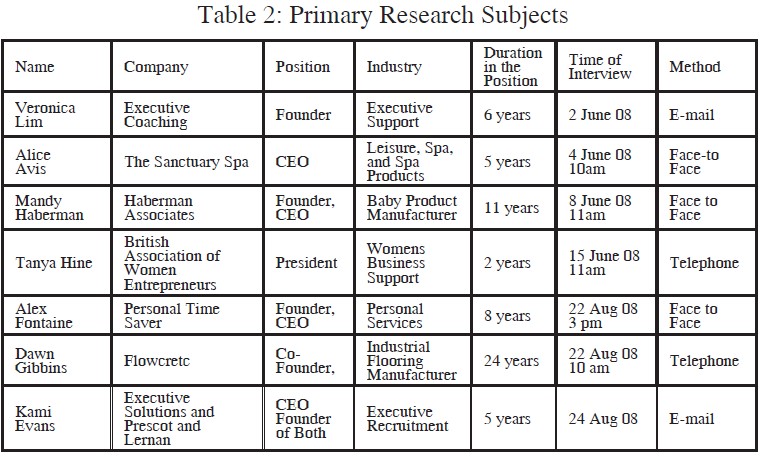

The majority of information gathered for this qualitative report came from personal interviews. A total of seven entrepreneurs were interviewed either face-to-face, via telephone, or via e-mail by the researcher, (see table 2). All of the interviews were sourced through the researcher’s previous contacts or through internet research. The questions asked in the interviews and information gathered referred to the main topics determined from the first step of the analysis.

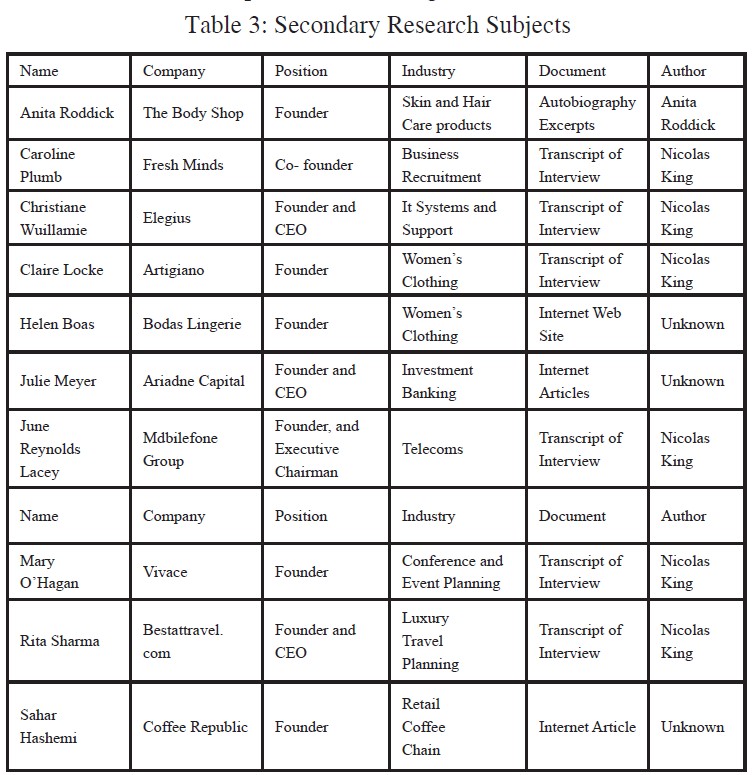

Secondary Research

In order to ensure the candidates being studied, represented the United Kingdom further research was conducted and profiles were brought in to be examined. These include autobiographies, magazine articles, and transcripts written by other researchers. Specific attention was made when selecting these subjects to ensure they represented a variety of geographic locations, industries, experience and backgrounds.

Assumptions

Throughout the research collection and analysis there are several assumptions that must be made. The primary research comes from a variety of women entrepreneurs within the United Kingdom. Because it

is not possible to interview every successful woman entrepreneur in the United Kingdom, a sample had to be taken. An assumption made is that the women in this study are a good representation of women entrepreneurs in the United Kingdom. Also, another assumption made is that these women openly shared all their experiences with the researcher. It is assumed that they did not hold back anecdotes or experiences that they may be embarrassed or nervous about sharing with others. Several secondary

research papers were also used during the course of the analysis. It is also assumed that these papers contain accurate information regarding reflection of an entrepreneur’s background and experiences.

ANALYSIS

As discussed in the methodology section, content analysis is used to determine key themes and concepts throughout the transcribed text. Prior to completing the actual analysis several key steps were completed. These included identifying the main questions and constructs involved, identifying the texts to be examined, extracting the most frequently used words in the texts, and using an inferred category scheme to categorize the keywords. In part one of the analysis section, these categories will be broken down and examined in more detail. The second part of the analysis section will compare the main themes and concepts, from part one, to the norms of the industry.

For this particular research paper, word sense and phrases will be used as the unit of analysis. There is some evidence that shows specific words and phrases have substantially higher reliability than sentences, paragraphs, and documents. The next step is to determine the key words that occur most frequently in the analyzed text. Advanced keywords and key phrase extraction technology for content analysis and search engine optimization makes this process easier, quicker and less flawed. The software breaks down the text into key phrases or words, organized by frequency of occurrence. Counts of occurrences at the level of the unit of analysis provide raw frequencies but the true added value of content analysis is the classification of units into categories. The categories determined by the researcher are: People, Support, Product / Industry, Lifestyle, Money, Education, Business, and the use of Positive and Negative words.

Part One: Content Analysis

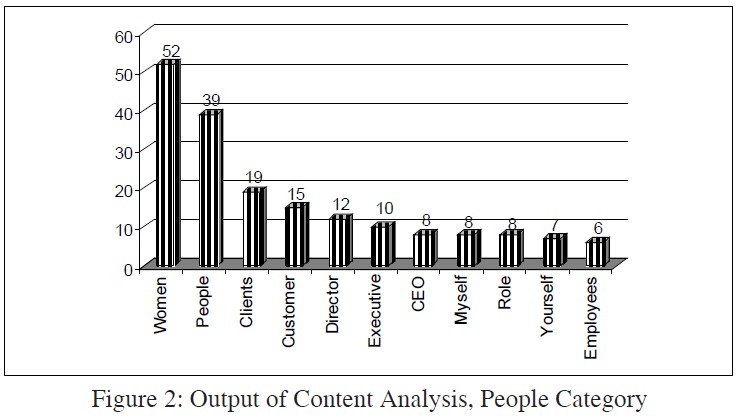

PEOPLE

Women

The word women’ was mentioned significantly more than any other word in the research, a total of fifty-two times. Although this is just a result of the questions asked and the subject matter at hand, it is worth considering. Many of the women interviewed had strong ties with other women and expressed their inner connection with one another. Dawn Gibbins (2008, interviewed) from Flowcretc says she “cherishes the time” she spends talking and presenting to women’s interest groups. She feels there is a

lot of sharing and networking going on between them. Alice Avis (2008, interviewed) of The Sanctuary Spa said that “women are in touch with other women, they tend to come up with good business ideas for women because they understand the market.”

People

It is no surprise that the word ‘people’ is also commonly used, thirty-nine times. Many references were made to concept of surrounding yourself with positive people and using these people to support success. Kami Evans (2008, interviewed) of Prescot and Leman said “Always surround yourself with people that are better than you.” Co-founder of Flowcretc Dawn Gibbins’s (2008, interviewed) focus on people has been a large part of her company’s success in the industrial flooring sector; she says “teamwork and people are key”.

Clients and Customers

The concept that clients are the most important part of an entrepreneur’s business is a very common subject amongst the researched text. The words ‘client’ and ‘customer’ were counted a combined thirty-four times. The exact quote, “clients come first” was articulated by both Veronica Lim (2008, interviewed), from Executive Coaching, and Alex Fontaine (2008, interviewed) from Personal Time Saver. Mary O’Hagan of Vivace expressed her affection for her clients when she said, “Most of my clients

are people I call friends.”

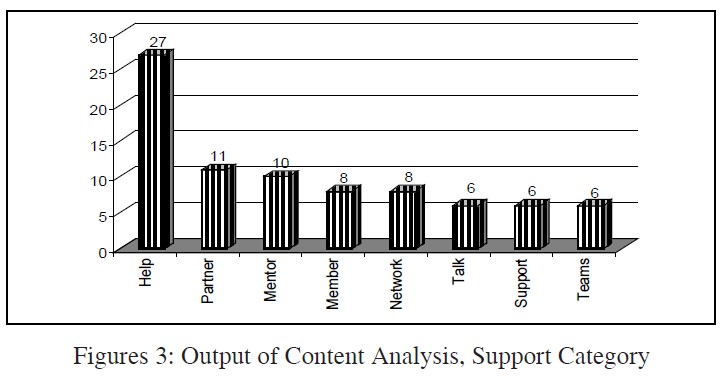

SUPPORT

Various types of supporting activities are required to facilitate women entrepreneurship development (Carter and Cannon, 1988). Women entrepreneurs in the UK are driven by following support activities.

Help

Similar to substantial use of the word ‘people’, the word ‘help’ is used a significant number of times. Women entrepreneurs talked about receiving help, asking for help, and actions that have helped them along the way. Mandy Haberman (2008, interviewed), from Haberman Associates said “Know what you do best and know what you will need help in”.

Partners

Many of the women in study either started up in association with partners or acquired partners along the way. It is interesting to note that the term was used in a negative connotation by women who acquired partners whereas it was used in a positive sense by women who started their business with partners. Mandy Haberman (2008, interviewed) discovered that partner hurt her business. When Haberman Associates grew to a size too big to handle on her own, she got some partners in but unlike her they did not have the innate understanding of the product, market, and need. Anita Roddick also found out, about the disadvantages of sharing control, the hard way. She appointed a managing director to help take over some of the management responsibilities from her. In the end she ‘felt his methods frightened the staff’, promoted “in-fighting and competition and diminished the unique qualities of The Body Shop. However, Veronica Lim (2008, interviewed), from Executive Coaching has a very different view of her partner. She said, “My partner was incredibly supportive and encouraging. We would speak every day in the early days to help keep each other on track.” One of the differences between these examples is that Mandy Haberman (2008, interviewed) and Anita Roddick gave away control of the business while Veronica Lim 2008, interviewed) shared the power from the start.

Mentor, Member, Network, Support, and Talk

‘Mentor’, ‘member’, network’, ‘talk’, and ‘support’, although individually mentioned several times, put together are mentioned a significant amount. The concept of connecting, communicating, and sharing with other people is unmistakably portrayed through the use of these words. The women in the study talked about the benefits of learning from a mentor. They spoke about the importance of networking and meeting new people.

• Mary O’Hagan from Vivace highlighted the value of a person with whom, the entrepreneur can discuss business problems with, like a mentor. Her mentor is Robin Cooper, a specialist in the marketing and conference business with nearly fifty years experience. She has put him on her payroll and says his appointment is one of the best decisions she has ever made.

• Caroline Plumb from Fresh Minds, highlighted that business should be started with a strong reason. “When they talk about business, people often talk about setting up on your own or going it alone. But that is completely the opposite of what needs to happen. It ‘s about creating the network of people you need to support, whether that is friends and family, customers, suppliers, cheerleaders, advisers or investors — and I think women can be good at that”.

• Kami Evans, 2008 (interviewed) from Presscott and Leman, highlighted the importance of talking about the entrepreneurial venture and said, “Talk — Let people know what you are trying to do, even if they are outside of your field of business. They may be able to share and apply knowledge to your business. They may even be able to find your first product, client, employee”

• Dawn Gibbins (2008, interviewed) from Flowcrete, cherishes the time she spends talking and presenting to women’s interest groups as she always feels there is lots of sharing going on there.

• Anita Roddick from The Body Shop, reaffirmed this, when she said “The sad thing in this country is that women in business don ‘t talk to each other enough.”

As the quotes show, sharing and talking can often provide the support a female entrepreneur needs.

Figure-4 shows that successful women in the UK are more likely to be found in business services (50%) as compared to other successful women around the world. This may simply be a result of the researcher’s network and the sourcing of the subjects. However, it is important to understand the reasone behind why these women have chosen their particular industries. Mandy Haberman (2008, interviewed) from Haberman Associates started her business to help solve the needs of her new-born daughter. Claire Locke from Artigiano says importing clothes from Italy was “the only think I ever wanted to do”. And Sahar Hashemi started Coffee Republic because she ‘loved the idea as a customer”.

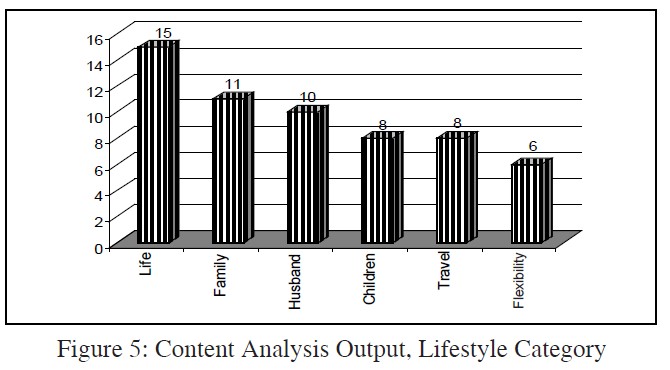

LIFESTYLE

Life

Many of the subjects of this study have families while others are single. The most common characteristic across them all was that they ensured they had an active lifestyle out of work. This is likely why the word ‘life’ was most commonly used.

Family, children, husband, travel, flexibility

It is positive to see that ‘family’, ‘husband’, and ‘children’ followed as the second, third, and fourth most commonly used words. Alice Avis (2008, interviewed) from the Sanctury Spa and Mandy Haberman

(2008, interviewed) from Haberman Associates remember working early mornings, late evenings, and weekends so that they could spend time at home when their children were growing up. However, Alex Fontaine (2008, interviewed) from Personal Time Saver expressed that it might be difficult to adjust with husband, as “He would not put up with me going out at eight o ‘clock at night on an emergency situation.” However, she does enjoy the flexibility that making her own schedule provides. Whereas, Rita

Sharma Bestattravel.com and Dawn Gibbins (2008, interviewed) balanced themselves by integrating their personal life with their businesses by from Flowcretc, hiring and working with their husband.

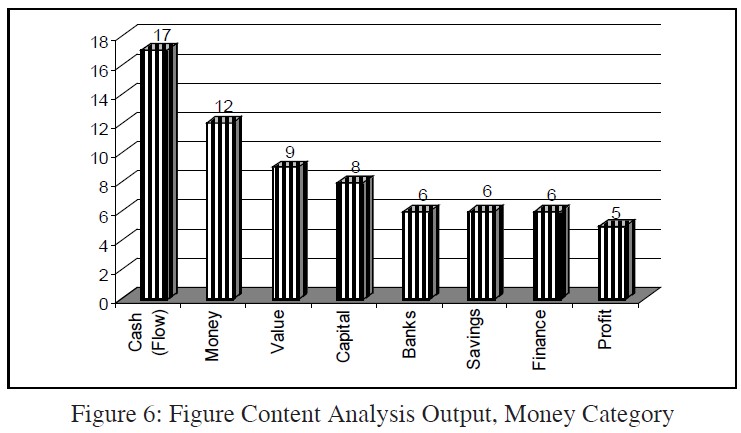

MONEY

Cash and Cash Flow:

Numerous subjects stressed the importance that women need to understand cash flow. Both Mandy Haberman (2008, interviewed) and from Haberman Associates and Alice Avis (2008, interviewed) from the Sanctuary Sparemember struggling to get orders in advance of production for their products, to ensure the proper flow of cash. Alice Avis said, “Women need to understand the value of cash flow as well as the difference between cash flow and profits”.

Money, Value and Capital

The word ‘money’ was used in a variety of different ways. It is interesting to note that an array of women both supported and contested the use of personal savings for a business. Kami Evans (2008, interviewed) from Prescot and Lernan, said. “Always use other people’s money to start up.” However, Alex Fontain (2008, interviewed) from Personal Time Saver supports using own money to start up and borrow later if needed. She said, “This makes it more of a reality, and since it is your own money you will

be more careful with it.”

Banks, Savings, Finance and Profit

Throughout the research no particular one way stood out as the most common financing method and content analysis backs this up. More interesting is that the word ‘profit’ falls at the bottom of the list, having only five mentions. This supports the statement in the literature review that women tend to be less motivated by making money (Cromie, 1987). When the studied women entrepreneurs, were asked to express the importance of education and experiences, most of them talked a great deal about the things they had learned. This included lessons from an earlier corporate life, past mistakes, other people, and the future ability to keep learning from everything they did. Kami Evans (2008, interviewed) spoke

of how important it is to learn something from everyone that you meet and Alex Fontaine (2008, interviewed) from personal time-saver spoke about how much she learned from her previous occupation. Lessons learned from past failures were also a common theme.

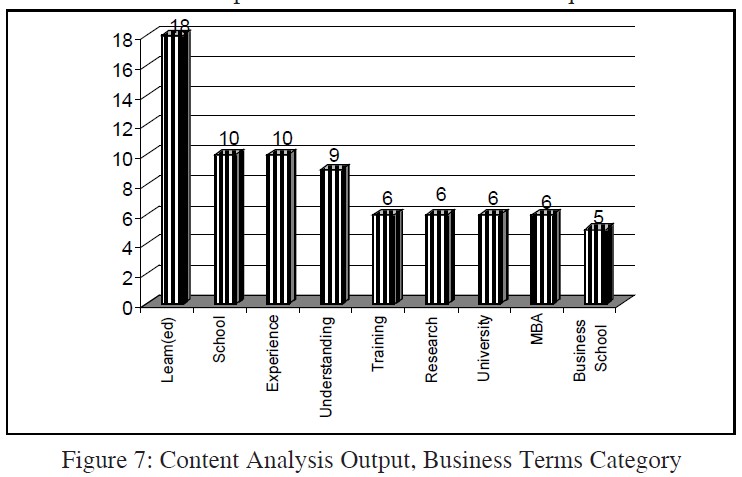

EDUCATION

Many of the women expressed that education is very important but admitted that only education can not ascertain success. For example, Alice Avis (2008, interviewed) from the Sanctuary Spa Dawn Gibbins (2008, interviewed) from Flowcretc and Alex Fontaine (2008, interviewed) said, their education was helpful but success is not about the qualifications.

‘General management skills are required to organize the physical and financial resources needed to run a successful venture.” (Wickham, 2004) He laid out some important general management business skills that a successful entrepreneur must exemplify, these are: (a) strategy skills: (b) planning skills: (c) marketing skills (d) financial skills: and (e) management skills: Confidence, opportunism, and determination are common characteristics which can be observed in entrepreneurs (Lambing and Kuehi, 2003; Kirby, 2003 and Wickham, 2004). By the analysis of responses, from women entrepreneurs interviewed for this study, it is evident that they exude confidence, belief, and assurance in both their own ability and their companies.

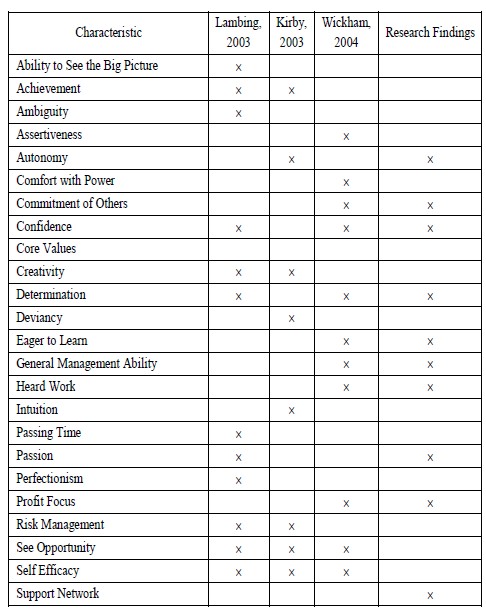

PART TWO. COMPARISON OF NORMS

There are numerous accounts by researchers, of entrepreneurial characteristics (Lambing and Kuehi, 2003; Kirby, 2003; Wickham, 2004). They recognize that their models are not perfect (Lambing and Kuehi, 2003; Wickham, 2004) and many fail to take into account that there may be differences between female and male entrepreneurial traits. The goal of this research is to build a framework of characteristics for successful women entrepreneurs. By comparing the output of the analysis of this research with some of the current models, a model specific to female entrepreneurs in the UK will appear. Table 4 lists three published authors and the characteristics they attribute to successful entrepreneurs, alongside the characteristics that have been found in this research.

Table 4: Comparison of Norms and Entrepreneurial Traits to Research

Lambing and Kuehi (2003) claim that entrepreneurs see things in a holistic sense; they have the ability to see the big picture when others see only parts. Entrepreneurs act on their ideas because they have a high need for achievement (Lambing and Kuehi, 2003; Kirby, 2003). However, it is the prospect of achievement (not money) that motivates them. Money is only important as a measure of success. (Kirby, 2003) In this research, it is seen that women are more motivated by achievements and success than

money. It may be that achievement is a relative term and therefore each woman talked about their achievements in their own way, therefore the content analysis was not able to recognize the repetition. Lambing and Kuehi (2003) said that the life of an entrepreneur unstructured; no one sets up schedules or step-by-step processes. However, this research does not uphold this statement. Many of the women in this study, including Mandy Haberman (2008, interviewed), Alice Avis (2008, interviewed), and Dawn

Gibbons (2008, interviewed) followed tight schedules. These particular women had families at home and therefore were very particular about how their daily schedule was conducted. On the other hand, Alex Fontaine (2008, interviewed) made sure that her schedule had room for ambiguity as her business demanded it. Therefore, no conclusion can be made on this particular characteristic. Wickham (2004) claimed it is important for an entrepreneur to know what they want to gain from a situation and more

importantly not be frightened to express their wishes. Mandy Haberman (2008, interviewed) expressed this as one of the obstacles she had to overcome, saying ‘It took me a long time to understand the balance of what I wanted to be done, and what others thought I should do.”

A characteristic that appears in many models is that of autonomy. Entrepreneurs want to be in control — hence they have been found to have a higher need for autonomy and a greater fear of external control than many other occupational groups, (Caird, 1991; Cromie and O’Donoghue, 1992). The examples of both Mandy Haberman and Anita Roddick having trouble with their business after sharing control of the business supports that women entrepreneurs have a need for autonomy. This statement is supported by research completed by Buttner and Moore (1997). Effective entrepreneurs are aware of the power they possess, are comfortable with the power, and recognize it as an asset (Wickham, 2004). However, this

was clearly not a concept that came across during the analysis of this research. This may be a clear result of gender differences but there is not enough research available at this time to make a clear conclusion.

The women entrepreneurs in this study expressed an obvious commitment to clients and customers. This focus on the client and satisfying their needs helped Veronica Lim from executive coaching, and

Alex Fontaine from Personal Time Saver, build their success. Although this is not a gender-specific characteristic it is clearly a key success factor for women entrepreneurs. “Entrepreneurs are confident in their abilities and the business concept. They believe they have the ability to accomplish whatever they set out to do (Yarzebinski, 1992). Nearly every authority on entrepreneurship recognizes the importance of self-motivation and self-determination for entrepreneurial success. (McNerney, 1994). The entrepreneur must demonstrate that they not only believe in themselves but also in the venture they are pursuing” (Wickham, 2004).

Determination, resilience, and tenacity despite failure are all common themes when describing entrepreneurs (Lambing and Kuehi, 2003; Wickham 2004). Because of the hurdles and obstacles that must be overcome, the entrepreneur must be consistently persistent. Many successful entrepreneurs succeeded only after they had failed several times (Lambing and Kuehi, 2003). This holds true for this research as three women had previous start-ups. Past failures and problems did not set these

women back; they all looked at them as learning experiences. According to Kets de Vries (1977) an entrepreneur is “an anxious individual, a non-conformist poorly organized and not a stranger to self-destructive behavior”. Many consider good entrepreneurs to be inquisitive and eager to learn (Wickham, 2004). They are never satisfied by the information at hand and typically seek more. They are aware of both the skills they have and their limitations and are always receptive to a chance to improve their

skills and develop new ones (Wickham. 2004). It is clear that the women in our survey embody the ideal of continuous learning and inquisitiveness.

Along these lines, Wickiiam (2004) and Garrett (2006) also stressed the importance of an entrepreneur’s ability to be profit-focused and to make money. However, research shows that women tend to be less motivated by making money than men. Nonetheless, this does not make the importance

on profit and financial understanding any less important for women. The content analysis shows that the women studied rely heavily on cash flow as a means to analyze the success of their businesses. In the world of profit measurement, there has been a trend towards cash flow accounting which promotes proper recognition and management of cash flows management of cash flows. Smith (1975) argued that, “whether or not the business survives is a matter of cash flows, not a matter of an intangible thing called

profit”. Therefore, successful women entrepreneurs may not be in business to make profits, however they do understand the importance of financial literacy and cash flow. Kirby (2003) reveals that entrepreneurs are intuitive rather than rational thinkers. Instead of adopting a structured, analytical

approach to problem solving, it is believed that they prefer a more intuitive approach. There is nothing in this study that either confirms or denies this statement and therefore this will remain inconclusive. “Entrepreneurs are aware that time is passing quickly and they therefore often appear to be impatient” (Lambing and Kuehi, 2003). However, past research shows that women tend to expand more slowly and carefully (Gracie, 1998) Nothing in this research suggests that the women surveyed had a hurry-up attitude and therefore this characteristic does not appear to apply to females.

Many suggest that by the very nature of their activities and roles entrepreneurs are risk-takers (Kirby, 2003; Koh, 1996). However, even this statement contradicts other findings such as Brockhaus (1980) whose work indicated that there are no significant differences in their risk-taking ability between entrepreneurs, managers, or the general population. Stanley (2004) supported this when he expressed that a key entrepreneurial trait is risk avoidance. This research does not clearly demonstrate either that the women surveyed are risk-takers or risk-averse, and therefore the present research is inconclusive on this matter.

Studies have suggested that the concept of self-efficacy influences a person’s entrepreneurial intentions (Boyd and Vozikis, 1994). Self-efficacy has been defined as a person’s belief in his or her capability to

perform a task (Lambing and Kuehi, 2003). This could also be classified as confidence. Therefore for the purpose of this study, self-efficacy will fall under the category of confidence. Although women clearly have a need for autonomy in their businesses there is also a clear need for support and help. The word ‘help’ was used an astonishing twenty-seven times and was the fifth most relevant word used. Veronica Lim from executive coaching, works along with her business partner and coach; Mary O’Hagan from

Vivace, trusts her mentor, and Dawn Gibbins from Flowcretc, works with her women’s networking groups. These are examples of how women use support networks to develop their successful businesses.

CONCLUSION

Research shows that women in the UK have a greater fear of risks than men and therefore are less likely to start up their own venture (Brooksbank et al., 2006). Female population that does participate in entrepreneurial activity lack the resources and support to ensure their long-term success. The purpose of this investigation was to build a model of characteristics of a successful female entrepreneur in the United Kingdom. This model can act as a confidence builder to remind women that they have the necessary characteristics to be successful. There are many characteristics studied that proved inconclusive in the scope of this paper. This does not say that they are not important characteristics for female entrepreneurs to embody, but that the necessity of them could not be proven through the research in this paper. These included: holistic thinking, need for achievement, ambiguity, assertiveness, comfort with power, creativity, intuition, perfectionism, risk management, and opportunistic. Entrepreneurs want to be in control (Kirby, 2003), and female entrepreneurs are no different. They value individualism and freedom. They often have an innate sense of their business and their products, and this sense can not be transferred. Overall female entrepreneurs are very involved with the people around them. This includes their peers, employees, partners, and customers.

Entrepreneurs are confident in their business and their own abilities (Lambing and Kuehi, 2003; Wickham, 2004). Having a positive outlook is critical to success. This holds true for female entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs understand that everything might not go as planned, in the first attempt and after things have gone wrong they learn something from the experience and use that to increase the chances of success the next time around (Lambing and Kuesi, 2003; Wickham, 2004). This holds true for female entrepreneurs as well, they demonstrate strong tenacity despite their previous failures. Good entrepreneurs are always eager to learn (Wickham, 2004), and female entrepreneurs are no different. They keep an open mind, are inquisitive and learn from their mistakes. Trying, experiencing, failing,

and understanding are all tools that females use to develop themselves as better entrepreneurs.

REFERENCES

Bailyn, L. (1993), SMR Forum: Patterned Chaos in Human Resource Management, Sloan Management Review, 34(2), pp. 77-83.

Baker. M., Aldrich, H.E., and Liou, N. (1997), Invisible Entrepreneurs: The Neglect of Women Business Owners by Mass Media and Scholarly Journals in the USA, Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, pp.221-238.

Barclays (2000), Women in Business: The Barriers Start to Fall, London, Barclays Bank plc.

Bell, J., Ibbotson, P., McClelland, E. and Swail. J. (2005), Following the Pathway of Female Entrepreneurs, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, Vol.1 1, No.2.

Birley, S. (1989), Female Entrepreneurs: Are They Really Any Different? Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp.32-7.

Boyd. N.G. and Vozikis, G.S. (1994), The influence of Self Efficacy on the Development of the Entrepreneur, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Summer, pp. 63.

Brush, C.G. (1992), Research on Women Business Owners: Past Trends, a New Perspective, and Future Directions, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol.16 No.4, pp.5.

Brush, C.G., and Edelman, L.F. (2000), Women Entrepreneurs: Opportunities for Database Research. In J.A. Katz (ed.), Databases for Study of Entrepreneurship, Volume 4, pp. 445-485.

Brooksbank, D. Harding, R. Hart, M. Jones-Evans, D. Levie, J. O’Reilly, M. and Walker, J. (2006), United Kingdom GEM 2005 National Report, Global Entrepreneurship Report, 22 Feb.

Buttner, E.H. and Moore, D.P. (1997), Women Entrepreneurs, Moving Beyond the Glass Ceiling, Sage Publications, London, United Kingdom.

Buttner, E.l-l. and Rosen, B. (1992), Rejection in the Loan Application Process: Male And Female Entrepreneurs’ Perception and Subsequent Intentions, Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 30 No. 1, pp.58-65.

Caird, S. (1991), The Enterprising Tendency of Occupational Groups, International Small Business Journal, 9(4), pp.75-81.

Carter, N.M., Williams, M., and Reynolds P.D. (1997), Discontinuance among new firms in retail: The Influence of Initial Resources, Strategy, And Gender, Journal of Business Venturing, 12, pp. 125-145.

Carter, S. and Cannon, T. (1988), Women in Business, Employment Gazette, Vol. 96 No. 10, pp.565-71.

Carter, S. and Rosa. p. (1998), The Financing of Male and Female Owned Businesses, Entrepreneurship and Research Development, Vol. 10 No. 3, pp. 225-41.

Catley, Suzanne and Hamilton, R.T. (1998), Small Business Development and Gender of Owner, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 17 Issue 1, pp.75.

Charboneau, F .J. (1981), The Woman Entrepreneur, American Demographics, Vol.6 No.3, pp. 21 -3.

Cochrane, 1. (2006), Starting Up, Design Week, May Supplement, Vol. 21, pp.59-63.

Cromie, S. (1987), Motivations of Aspiring Male and Female Entrepreneurs, Journal of Occupational Behaviour, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp.25 1-61.

Cromie, S. and J. O’Donoghue (1992), Assessing Entrepreneurial Inclinations, International Small Business Journal, 10 (2), pp.66-73.

DeMartino, R. and Barbato, R.(2003), Differences Between Women and Men MBA Entrepreneurs: Exploring Family Flexibility and Wealth Creation As Career

Motivators, Journal of Business Venturing, Nov, Vol.18 Issue 6.

DTI (Department of Trade and Industry, UK)(2006), Statistical News Release on Female

Entrepreneurs, P/2006/776, 15th December, 2006, available from- www.dit.gov.uk/

SME/define.htm.

DTI Data base (2006), Documents on Female Entrepreneurs in the UK, Collected from Database (2006) of DTI Library Fisher, A. (2004), Why Women Rule, Fortune Small Business, Jul/Aug. Vol. 14 Issue 6, pp.47-52,

Flick, U. (1998), An Introduction to Qualitative Research, Sage Publications, London, United Kingdom.

Garrett, S. (2006), The True Entrepreneur, Financial Planning, May, Vol. 36 Issue 5, pp.1 15- 116.

Goffee, R. and Scase, R. (1983), “Business Ownership and Women’s Subordination: a Preliminary Study of female Proprietors”, Sociological Review, Vol. 31 No. 4, pp. 625-48.

Goffee, R. and Scase, R (1985), Women in Charge, George Allen and Unwin, London,

United Kingdom.

Goffee, R., Scase, R. and Pollack, M. (1982), Why Some Women Decide to Become Their

Own Boss, New Society, Vol. 61 No. 1032, PP. 408-10

Gracie, S. (1998), In the Company of Women, Management Today, June, p 66-70.

Harding, R.K. (2003), United Kingdom Full Report, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 09 Jan.

GEM (2004), United Kingdom Full Report, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 22 Jan.

Hisrich, R. (1989), Women Entrepreneurs: Problems and Prescriptions for Success in the

Future, in [-lagan, 0., Rivchun, C. and Sexton, D. (Eds), Women-owned Businesses, Praeger, New York, NY.

Hisrich, R. and O’Brien. M. (1981), The Women Entrepreneur from a Business and Sociological Perspective, in Vesper, K. (Ed.), Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Babson College. Wellesley, MA.

Goffee, R. and Scase, R (1982), The Women Entrepreneur as a Reflection of the Type of Business, in Vesper, K. (Ed.), Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Babson College, Wellesley, MA.

Humphreys, M. and McClung, J. (1981), Women Entrepreneurs in Oklahoma, Review of Regional Economics and Business, Vol. 6 No. 2, pp. 13-20.

Hurst, N. (2005), Women Led Firms Make Gains Across Industries, Boston Globe, Dec. 25.

Insch, G. S. and Moore, J.E. (1997), Content Analysis in Leadership Research: Examples, Procedures, and Suggestions for Future Use, Leadership Quarterly, Vol.8, Issue 1, p1.

Kets de Vries, M.F.R. (1977), The Entrepreneurial Personality: A Person at the Crossorads. Journal of Management Studies, February, pp.34-57.

Kirby, D. A. (2003), Entrepreneurship. McGraw Hill, London, United Kingdom.

Klein, K. E. (2006), Make Way for Female Entrepreneurs, Business Week Online, March 6, p4.

Koh, H.C. (1996), Testing Hypotheses of Entrepreneurial Characteristics, Journal of Managerial Psychology, 11, pp. 12-25.

Krippendorff, K. (1980), Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology, Sage, Newbury Park, CA, USA.

Lambing, P. A. and Kuehi, C. R. (2003), Entrepreneurship. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River. NJ, USA.

McNerney, D.J., (1994), Truths and Falsehoods about Entrepreneurs. HRFOCUS, August 1994. pp.7.

Merritt, R.L. (1970), Systematic Approaches to Comparative Politics, Rand McNally, Chicago, IL, USA.

Mucha, T. (2006), Born or Made? Cram’s Chicago Business, July 10, Vol. 29 Issue 28, pp.18.

Orhan, M. and Scott, D. (2001), Why Women Enter into Entrepreneurship: An Explorative Model, Women in Management Review, Vol. 16 No. 5. pp.232-47.

Pratt, A. (2006), The Should and the Bad, Director, July. Vol.59, Issue 12, p16.

Prowess (2006) www.prowess.org.uk.

Rogoff. E.G. (2006), Business Success Starts with Being a Good Listener. Business Journal (Central New York), May 19, Vol. 20 Issue 20, pp.14.

Schreier, J. (1975), The Female Entrepreneur: A Pilot Study, Center for Venture Management, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Sexton, D. (1989), Growth Decisions and Growth Patterns of Women-owned Enterprises in Hagan, 0. and Sexton. D. (Eds), Women-owned Businesses, Praeger, New York, NY, USA.

Sexton, D. and Smilor, R. (Eds) (1986), The Art and Science of Entrepreneurship, Ballinger, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Stanley, T.J. (2004), Millionaire Women Next Door: The Many Journeys of Successful American Businesswomen, Andrews McMeel Publishing, Kansas City, MO, USA.

Stevenson, L. (1986), Against All Odds: the Entrepreneurship of Women, Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 24 No. 4, pp. 30-6.

Still. L.V. and Tirnms, W. (2000), Making a Difference: The Values, Motivations and Satisfaction, Measures of Success, Operating Principles and Contributions of Women Small Business Owners, Discussion Paper Series, Centre for Women and Business, The University of Western Australia, Perth, pp.3-18.

Watkins, J. and Watkins, D. (1984), The Female Entrepreneur: Background and Determinants of Business Choice: Some British Data, International Small Business Journal, Vol. 2 No. 4, pp. 21-31.

Weber, R.P. (1990), Basic Content Analysis. Sage, Newbury Park, CA, USA.

Welsh, M. (1988), The Corporate Enigma: Women Business Owners in New Zealand, GP Books, Wellington, New Zealand.

Wickham, P.A. (2004), Strategic Entrepreneurship. Pearson Education, London, United Kingdom.

Wojahn, E. (1986), Why Women’s Businesses Don’t Turn Heads, Business Review Weekly, 6 November, pp 16-19.

Women’s Business Development Agency (2006), www.wbda.co.uk.

Yarzebinski, Joseph A., (1992), Understanding and Encouraging the Entrepreneur, Economic Development Review, Winter, 32.

Mohammed Shahedul Quader is Assistant Professor in the Department of Marketing Studies and International Marketing and Faculty of Business Administration University of Chittagong Chittagong, Bangladesh. Email: shahedulquader@yahoo.com